Teacher stress ‘spreads to pupils like a contagion’

“It’s about how good an actor you are,” Corinne Lamoureux says. “I’d leave the classroom and cry, but I didn’t show it.”

The Cornwall-based primary teacher pauses. “I’m aware of another teacher - she cried in front of the class on several occasions.”

No one would be surprised to hear that teachers are stressed - or, indeed, that they are more stressed than they have ever been before. Workload, funding pressures and the accountability system have all combined to create a teaching workforce struggling with its mental health.

Previously, this was seen as a problem for teachers, headteachers and unions to deal with, but which parents and politicians might choose to ignore. Now, however, it is becoming apparent that teachers’ mental ill-health has a much broader impact than previously assumed. It has become everyone’s problem.

Researchers have uncovered physical evidence showing that stress can be passed - like a virus - from teachers to pupils.

Studies are also showing that stress does not just lead to teachers burning out and leaving the job. It can turn those who hang in there into autocratic, punitive workaholics.

Teachers’ poor mental health affects their classroom performance, limiting pupils’ academic achievement and leading to low grades. It also compromises pupils’ mental health, causing classroom stress and an increase in peer-on-peer bullying.

‘Difficult to manage’

“There’s evidence that children pick up the emotions of teachers,” says Gail Kinman, professor of occupational health psychology at the University of Bedfordshire.

“Stress passes from person to person. It moves around the classroom like a contagion, which is very difficult to manage.”

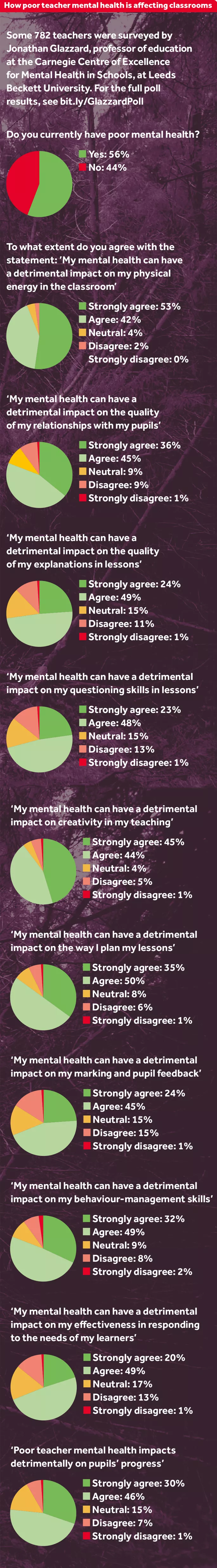

Jonathan Glazzard, professor of education at the Carnegie Centre of Excellence for Mental Health in Schools, at Leeds Beckett University, has just launched an extensive study into the ways that teachers’ stress can affect pupils’ academic performance.

Initial results reveal that, of the 782 primary, secondary and further-education teachers questioned by Glazzard, 56 per cent were suffering from poor mental health, with more than half of those saying that this was confirmed by their GP. And more than three-quarters - believed that poor teacher mental health had a detrimental impact on pupils’ progress.

“I have anecdotal evidence from schools that it really does impact,” Glazzard says. “I’ve been talking to senior leaders, who say to me they have evidence that poor teacher mental health impacts on the progress of children.”

Teachers who are suffering from poor mental health are more likely to take time off work. Recent figures produced by the Liberal Democrats showed that there were 3,750 teachers on long-term leave for stress during the academic year 2016-17. This represented an increase of 5 per cent against the previous year. And teachers have taken 1.3 million days off work over the past four years because of stress or mental health problems.

The uncertainty and the long-term reliance on supply teaching resulting from such absences have had an inevitable effect on pupils’ academic results. But this is far from the only way in which poor teacher mental health can take its toll in the classroom.

Lisa Matthewman, an organisational psychologist and principal lecturer at Westminster Business School, lists a range of symptoms that she has seen affect teachers, through her own research and reviews of other studies.

“They may have mood swings - become more irritable, more agitated,” she says. “They might have headaches.”

This is backed up by recent data from teacher helpline the Education Support Partnership. In a survey of 1,250 teachers, the partnership found that 56 per cent of respondents had noticed mood swings, irritability, changes to appetite or a tendency to procrastinate. Half of those teachers surveyed also said they had experienced physical symptoms, such as headaches, migraines or dizziness.

In Glazzard’s study, the vast majority - 95 per cent - of teachers said that their mental health could have a detrimental impact on their physical energy in the classroom. Questioned further, a clear majority added that their mental health affected the quality of their explanations to pupils, their behaviour management, their lesson-planning and their classroom creativity.

Lamoureux experienced this first-hand. “When you’re stressed, you spend a lot of time being a busy fool,” she says. “You scattergun everything. You don’t plan the whizzy lesson you might.”

Such a scattergun approach is typical of teachers struggling with mental ill-health, Matthewman says: “They’re using work as an escape - as an addiction in itself. They become a workaholic, leading to emotional burnout. Perhaps they’ll be less engaged with students than they once were. They may be acting out in the classroom: taking out their frustrations on the students to some extent. They might be more prone to being autocratic and punitive in their approach.”

She also suggests that teachers could lose sight of appropriate boundaries between themselves and their pupils. “Managing the relationship boundary can become quite confused,” she says. “It may become increasingly blurred. The adult and the minor - that may be lost somewhat when someone’s incredibly stressed or anxious.”

Boundary issues

This blurring of boundaries between adult and child can be manifested in a number of ways. The Education Support Partnership gives the example of a teacher who, like Lamoureux’s colleague, broke down in tears in front of her class.

And, at a recent parliamentary hearing into children and young people’s mental health, one young witness told MPs: “Teachers are visibly stressed in lessons. I even know of one teacher who had a panic attack in the middle of the class. It was very distressing for the teacher concerned, and even more distressing, I would argue, for Year 8 sitting in that class.”

But Kinman says that the lack of an appropriate boundary can be even more insidious. She cites a 2016 study conducted by the University of British Columbia, which tracked the stress levels of more than 400 pupils in 17 Canadian elementary schools. The academics found that those pupils whose teachers reported feeling burnt-out tended to display higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol than pupils whose teachers were not stressed.

“If teachers are very stressed, they may be able to put on a face for a while,” Kinman says. “But eventually that will crumble. And, because teachers have such a powerful role in students’ lives, students won’t have the emotional stability that they need. Emotional contagion is very, very powerful indeed.”

Pupil response

In addition, there is evidence to suggest that pupils change their behaviour in response to perceived teacher stress. “They may reduce their demands: ‘I know you’re stressed, so I’m not going to put more burden on you,’” Kinman says. “Or they may play up more, because you’ve shown a little chink of weakness. Then you get a chain reaction, where you lose ability to maintain control.”

But it is not only pupils’ behaviour towards the teacher that can be affected. Poor teacher mental health also influences pupils’ behaviour towards one another, according to Chris Kyriacou, professor of educational psychology at the University of York.

Like Kinman, Kyriacou refers to a chain reaction: “Schools become pressured places, and then teachers are less able to devote time and support to pupils who are feeling stressed themselves. And we know that when pupils are feeling frustrated at school, they want to take it out on someone else.”

Kyriacou has studied the kinds of school environments that are conducive to bullying. He found that when pupils are feeling stressed and frustrated, they are more likely to resort to bullying their classmates.

“It’s not rocket science,” he says. “If schools feel under pressure, then teachers feel under pressure. And then pupils feel under pressure, and more of them are engaged in bullying.

“Then they’re more likely to end up truanting and more of them will end up being excluded from school. If you start to scrape beneath the surface, there are all those links going on.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters