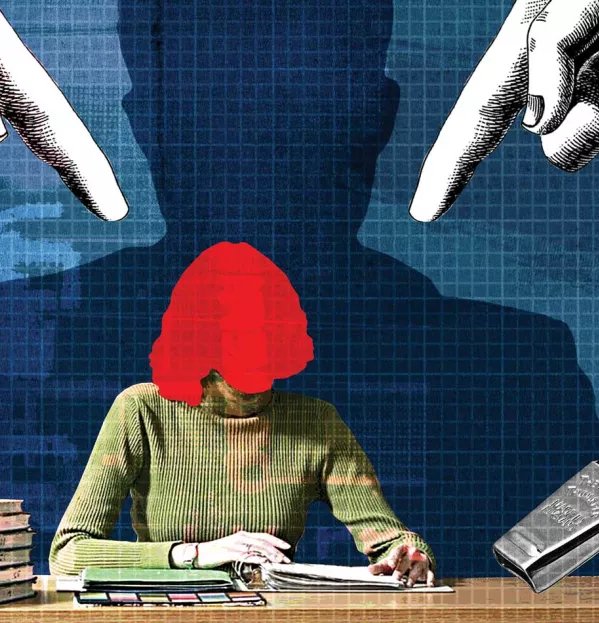

‘Teachers are too afraid to speak out’

Back in 2015, Norma Seith was a principal teacher in Dundee, heading up the city’s young mothers’ unit - a nursery based in a secondary school that enabled girls who became pregnant to continue their education.

The girls were taxied into school in the morning with their babies, whom they dropped off at the nursery, before attending classes. They socialised and interacted with their babies during break times and were also timetabled to learn from the experienced nursery nurses who worked there.

It was a great service - I know, because I visited it. Not as a journalist, but as Norma Seith’s stepdaughter.

However, in 2015, the decision was taken to remove Norma - who was also a guidance teacher in the school - redeploy her elsewhere in the city and save the head-of-unit salary of £44,000.

The secondary in which the service was based was due to merge with another school, and the plan was to put the unit in a new, standalone nursery. It would be run by the head of that nursery and a depute from the secondary, but Norma’s expertise and long experience in this specialised area - she had headed up the unit for close to a decade - would be lost.

‘Only one side of the story’

Throughout the whole process, there was no opportunity for Norma to give her professional opinion about the proposed changes. In fact, she was explicitly told not to approach local councillors, other than those for her area.

The impact was huge. It marred the final years of Norma’s career - a career that had spanned nigh-on four decades - and the service, which accommodated five students when Norma left, has not had a young mother through the door for a year and a half.

Norma would have liked to raise many concerns about her situation and what she viewed as the shortcomings of the new service, but she never got that opportunity. It was made clear to her that her future livelihood depended on her keeping schtum.

“What the council was hearing made such good financial sense,” says Norma, who retired from teaching in August, after spending several years as a support for learning teacher in another Dundee school. “I would have listened to that and made the same judgement as the councillors made. But they did not have all the facts - they were given only one side of the story.

“I was basically told to keep quiet. No one can ever know a service like the person running it, but I had no voice at all.”

When I ask about the unit’s closure, a spokesman for Dundee City Council says: “It would not be appropriate to comment on any individual case. There are well-established procedures open to all employees to raise any concerns that they may have.”

This sort of story has become topical of late, amid claims that there is a “culture of fear” in Scottish education preventing staff from raising concerns - making people who are willing to publicly share their experiences, like the now-retired Norma, extremely rare. There are also counter-claims that the powers-that-be will have the back of any teacher who does speak out.

The Scottish government insists that it wants to empower teachers and their schools. Education secretary John Swinney has said that staff should challenge any overly bureaucratic systems or processes piled on them from on high. When it comes to the new Scottish National Standardised Assessments (SNSAs), he has told teachers that if councils dictate a time window during which the literacy and numeracy tests must be sat - a move that is contrary to government guidelines - they should refuse to comply.

One of Swinney’s favourite pieces of advice, doled out in several recent speeches, is that teachers should “proceed until apprehended”. But as Larry Flanagan, general secretary of Scotland’s largest teaching union, the EIS, says: “That is easy to say but you are apprehended pretty quickly in Scottish education. Every time you take a step over the line, someone is telling you to get back.”

Recently, however, teachers have become less willing to put up and shut up.

An estimated 30,000 people marched through the streets of Glasgow in October, demanding a 10 per cent pay bump, and teachers and the organisations that represent them - such as the Scottish Guidance Association - have written open letters to the government in a bid to highlight problems.

The letters have expressed concerns about everything from “the disaster that is Curriculum for Excellence” to the “drastically underfunded” inclusion policy. According to a primary schoolteacher - who says she wrote an open letter after a colleague was barred by a manager from taking up an invitation to meet with Swinney - one of the “most concerning and frustrating issues with the state of the education system is the inability to be able to speak out about the problems we face”.

Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson seized upon that letter, saying during First Minister’s Questions on 4 October that there was “a culture of fear and secrecy” among teachers in Scotland, and that the threat of “repercussions for their careers” discouraged them from speaking out.

This prompted first minister Nicola Sturgeon to say that it was “unacceptable” for any council to discipline a member of staff for speaking out about problems. She added that if anyone had any concerns, they should write to her; recently, it was revealed that 120 teachers had taken her up on that offer (see box, page 18).

Around the same time, biology teacher Mark Wilson - whose own open letter to Sturgeon went viral in September 2017 - set up the Dear Madam President blog to provide “an anonymous platform for the open letter”, so that no teacher had to “worry about being exposed like I was”.

On the website, he writes: “Such is the worry about expressing any sort of opinion among teachers that, since starting this site, I’ve had more than a few contact me to ask if it’s safe to even ‘like’ or follow the page.

“That’s an unacceptable level of fear and a gross loss of freedom.”

When asked for an interview, Wilson says he would “love to express fully” what his experience has been, but that “in the present climate, it’s not something I can do”. He adds: “That in itself is a major problem.”

Risking ‘pariah’ status

Other teachers are only willing to share their views anonymously. A secondary modern studies and history teacher, who has been in the job for five years, says her major concern is about behaviour, but that to really take management to task over abusive pupils being returned to the classroom would be to risk becoming “a pariah” in her school. She would be branded “a tattletale” and would be passed over for promotion, she says.

The teacher is calling for a service where staff can report “everyday verbal and physical abuse in the classroom” so that the scale of the problem can be recorded and action taken. “I enjoy my job and my place of work is, 75-80 per cent of the time, a positive environment,” she says. “I benefit from having a very strong-willed and respected principal teacher as my first line manager, who is protective and encouraging of departmental staff.

“My current headteacher seems to think I am capable and has suggested I pursue training, which would be helpful should I wish to go for promotion. But I know this could all change if I speak out.

“I do not want to be sworn at by teenage boys (even considering their challenging personal circumstances). I do not expect to come home and listen to my partner describe yet another incident in which he has had a P1 pupil with severe autism spectrum disorder kick and punch his rib cage.

“Yet it happens frequently, and not just to me but to many, many teachers up and down the country.”

Meanwhile, a primary teacher says that “a speaking-out culture basically doesn’t exist in education”, which is why teachers resort to open letters and anonymous online posts. “Teachers are often too afraid to speak up in their own staffroom and potentially feel the wrath of a headteacher, never mind speak out on a national level,” he adds.

Even teachers tweeting about Scottish education say they have been summoned before the head when their 280-character offerings were deemed too negative.

Flanagan says that some councils are “hypersensitive” about employees criticising them, and “try to intimidate people into not airing issues in public”. However, he explains that it is more complicated than teachers simply having “an absolute right to free speech”, because, in the state sector, their employer is the local authority.

“There’s a balance,” Flanagan says. “We do accept that there is this fidelity clause as part of employment conditions. If you work for a council, you don’t have free rein to publicly criticise your employers or to use information that could be privileged - that you know about because you work for the council.”

Nevertheless, councils are guilty of abusing their position and taking a “Big Brother approach”, Flanagan argues. Teachers should be able to speak at union AGMs without receiving letters from directors of education reminding them that they are council employees, he says. They should also be able to meet with elected politicians and take part in campaigns such as Play Not Tests, which opposes SNSAs for P1 pupils.

This lack of freedom is, indeed, a problem, according to Patricia Anderson, the leader of a campaign that calls for parents to have an automatic right to defer the start of their child’s education if they are only 4 years old.

Anderson says some teachers who are also parents are “afraid” to speak out. “Fear of disciplinary action has sadly, but completely understandably, gagged many of our supporters from speaking publicly about their experiences of applying for discretionary deferral funding,” she explains. “How can this be fair in a country where we are supposed to have freedom of speech and the right to a private life?

“How can criticising a process you have experienced in your capacity as a parent living in a particular local authority area be legitimately held against you in your unrelated capacity as an employee of that same local authority?”

Students’ best interests

Anderson argues that while doctors and nurses must prioritise the patient over their employer, teachers’ professional standards do not allow them to go against council policy to act in the best interests of the child.

The General Medical Council - which sets the professional standards that doctors follow - confirms that doctors must prioritise their patients. “They have a duty to put patients’ interests first and act to protect them, which overrides personal and professional loyalties,” says a spokeswoman.

The General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS), which upholds teachers’ professional standards, insists that these do refer directly to ethics. It highlights two relevant passages: one says that teachers should have “unswerving personal commitment to all learners’ intellectual, social and ethical growth and wellbeing”; the other states that “professionalism also implies the need to ask critical questions of educational policies and practices and to examine our attitudes and beliefs”.

The GTCS says its expectation is that any comments offered by staff should be given “in a professional and respectful manner as befits a professional teacher”. It adds that the local negotiating councils for teachers - which exist in each of Scotland’s 32 local authorities and comprise council officials and union representatives - are “the appropriate forums for teacher concerns to be resolved”.

Of course, anyone with concerns about a teacher, including a colleague, can report them to the GTCS - something that is happening more and more (see figures, page 17).

A GTCS spokesman says: “We cannot comment on a ‘culture of fear’ as this suggestion is within the employment environment of teachers and therefore not within the remit of GTCS. However, as with all education organisations in Scotland, if a ‘culture of fear’ does exist, we would be incredibly disappointed and consider that an inappropriate way in which to deal with the challenges facing teachers.”

Education Scotland, which is responsible for school inspections, also says that if a teacher has a concern, they should raise it with their local authority. Education Scotland does not have “a remit to resolve or investigate complaints about services that are provided by local authorities”.

However, the body carries out about 250 inspections a year, and points out that, during this process, “it is very important to us that we hear the voice of teachers”. If a teacher raises a concern, it can form part of the inspection findings, and be shared with the headteacher and local authority.

Education Scotland’s English equivalent, Ofsted, does have a complaints process, but it makes clear that any concerns should be raised with the school or governing body before the inspectorate is contacted.

An Education Scotland spokeswoman says: “We would recommend any teacher with a complaint regarding the level of service provided by a school to speak to their headteacher or contact the local authority in the first instance to discuss their concerns.”

But according to Protect - a charity that aims to stop harm by enabling safe whistleblowing - councils need to “get better at encouraging their employees to raise concerns”. Training should be provided, it says, and local authorities should engage with staff about whistleblowing arrangements and ensure they are clearly communicated.

The agenda of empowering schools has huge potential to address some of these issues, Flanagan believes. Teacher agency is “smothered” under the current system, but if staff felt more involved in the decisions that affected them and schools became more collegiate places, some of this frustration would dissipate, he says.

As Glasgow director of education Maureen McKenna recently put it: “The headteacher is but one player in an empowered system.”

A spokesman for local authorities’ body Cosla says: “Every local authority has structures in place to make sure that teachers are supported to be able to raise concerns where these exist. This includes the local negotiating council for teachers. In addition to this, there is strong trade union representation in Scottish education. And there is regular engagement between trade union representatives and the local authority.

“While we would not decry the experience of any teacher, we do not believe there is evidence to support claims of a ‘culture of fear’ in Scottish education.”

What is clear, however, is that this is far from a uniform view: “culture of fear” may be an emotive phrase that is ripe for exploitation by politicians, but it reflects genuine and widely held worries that many teachers have about speaking out.

Emma Seith is a reporter for Tes Scotland

Dear Nicola Sturgeon: ‘We’re underpaid and undervalued’

In response to claims that teachers were afraid to speak out about problems in education because this could jeopardise their careers, first minister Nicola Sturgeon invited people to write to her directly about their concerns. Around 120 teachers took her up on the offer. Here are exclusive excerpts from some of those letters:

* “My biggest concern is with the workload that teachers are expected to undertake on a daily and weekly basis. Many, if not most, work an absolute minimum of 50 hours weekly … the burden placed on teachers emotionally and mentally of consistently working far too many hours is ridiculous.”

* “The morale of your Scottish teachers is the lowest I have seen in my 10 years of teaching. The feeling is of being undervalued and very much overworked. I studied hard to be where I am, and I work hard. Each Inset day, all we hear about are the NEW changes to the curriculum before the previous NEW way has yet to be fully embedded. It is, honestly, soul-destroying never feeling like your best effort is good enough.”

* “I am writing this to you before we start our fight for a decent pay rise, and please believe me when I say your teachers have all had enough. We are tired, we are demoralised and we are most certainly now very much underpaid and undervalued for the skilled and exhausting job we do. We are all ready to stand up and have our say now - enough really is enough.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters