We need to wake up to teenage sleep problems

“Alexa, set an alarm for 6am,” I say, with the best intentions, after dousing my pillows and bedsheets in lavender spray and setting a sleep timer on my relaxation podcast. It’s 10.30pm. I lie down and make an honest

yet futile attempt at following the soporific instructions drifting across the room and begin to “empty my mind” of the nightly thought-opera that has started to stir to life.

Am I prepared for tomorrow? Breathe in. Have I locked the door? Breathe out. Should I check on my son, again? Breathe in … “Calm your mind and begin to empty your thoughts” … I’ve not texted my gran today. “Begin relaxing your muscles from the top of your head to the…” My head hurts.

Instead of relaxing and breathing, I begin calculating the hours of sleep I am going to get if I fall asleep now, compared with if I fall asleep an hour later … two hours later … three hours later. I have the apps, I’ve tried the melatonin and the valerian tea. I have blackout blinds and a weighted blanket. I refuse to have a TV in my room. I have plants that are meant to improve air quality hanging in baskets from the ceiling (that are, fittingly, dead).

Yet, here we are. It is now midnight. The sleep podcast is on its third loop and my mind is anything but empty: food, lessons, the dog’s dental appointment, the last conversation I had today with a colleague, if I should have sent that text or not, that one time when I was in my first year of university and fell down the library steps …The usual irrelevant, uncontrollable aspects of life that keep us all awake at night. The irony, though, is that I adore sleep. In fact, it’s probably one of my favourite things to do; but like most of the great loves of my life, it eludes me. I love the idea of it, but it never seems to come easily.

Despite this, I consider myself one of the lucky ones. I have the disposable income (barely) to invest in the sleep aids that are saturating the market. I have the knowledge and interest needed to research what makes sleep necessary and how to improve it, and, although it’s taken a good few years, I have the initiative and assertiveness needed to be able to pick up the phone and speak to my GP when it absolutely isn’t working, because I know that when your sleep suffers, your mental health suffers, too.

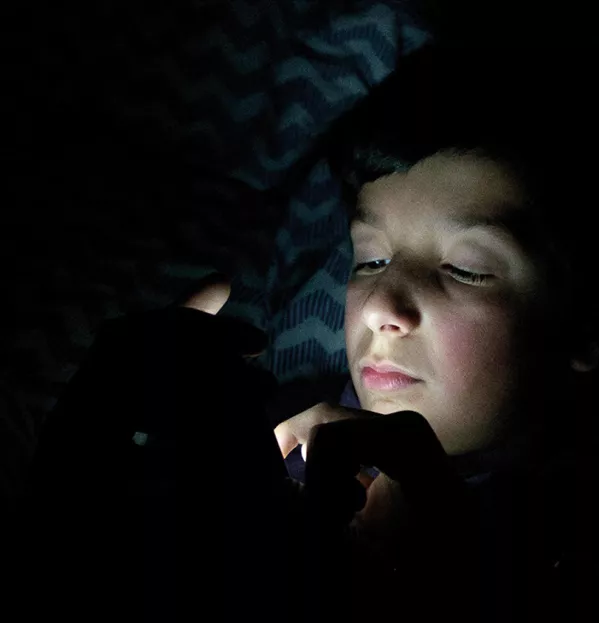

But for many of the exhausted young adults we see in front of us every day, this isn’t the case. For many of them, sleep hygiene means nothing more than clean bedsheets and clean teeth. For many of them, any kind of sleep routine is punctured by an endless cycle of instant online videos, images and social media notifications, which lead to spiralling thoughts about self-image and peer acceptance. For many of them, getting enough sleep is the tip of the proverbial adolescent mental health iceberg.

It will come as no surprise either that the amount of sleep a person gets directly correlates with their performance at work or, in the case of our young people, their performance at school. Sleep research suggests that a teenager needs eight to 10 hours of sleep every night. The more dubious among you may perhaps be snorting into your coffee while reading those numbers. And, yes, Margaret Thatcher did famously sleep for a mere fours every night, but, in spite of her indefatigability, we’re not all made of iron.

Eight hours might sound reasonable, especially for a teenager (I mean, all they do is sleep, right?), but bear in mind that this is the minimum. Would you be happy, as a teacher, if your students were scraping by on the bare minimum amount of work and effort needed to pass their coursework and exams? Teenagers aren’t even managing to get through the night with enough sleep to scrape the lowermost pass mark needed for a quality slumber, with most teenagers struggling to hit an eight-hour C.

And, yes, you’ve guessed it, the pandemic has had an impact on the figures. Lockdown destroyed the steady routine of the school day, which meant that our young people were going to bed later and waking up in a way that suited them. The one upside of this delay in bedtime schedules was that, for at least a short while, it actually benefited teenagers: this way of sleeping is more in line with their later biological body clock. And, during the pandemic, it has even been reported that a marginal number of teenagers have been sleeping for longer than before.

Nevertheless, whether individuals were getting more or less sleep, these changes made it much more difficult for teenagers to reset their routines when the school term resumed. And resumed it has, in all its sanitising, face-mask-wearing and socially distanced pedagogical glory.

For many of our young people, waking up naturally without the clanging chimes of an alarm has become more than just a weekend indulgence, and now parents are battling to keep their children’s sleep routine on course for an A grade. Adhering to a routine of sleeping and waking times is essential to prevent sleep disruption, and for the teenagers whom we encounter on the job every day, the removal of this routine has damaged their ability to readapt to a highly structured and early start to the day.

Not having a regular routine, together with the relentless academic and social pressure, is resulting in the stirrings of a collective anxiety and this, in turn, is causing a later and later sleep time for many of us who can’t nod off because we are anxiously ruminating over what the next day holds.

So, what do we do? Pick up our phones, obviously. Anything to distract us from the overwhelming and unpredictable nature of the world we live in. Teenagers are no longer using their phones just to relentlessly scroll through the vacuous void of social media, though. The devices that we once encouraged young adults to use less are now acting as a 24/7 portal to their academic lives, and this is not necessarily a good thing.

What was once used by them as an escape is now part of the bigger problem, with their phones permanently linked to their life in school. A constant reminder that they are not achieving their potential; that during perhaps one of the greatest disasters of their lifetime, they are not rising to their academic capabilities - let alone rising with their 6am alarms.

There is no doubt about it, though: smartphones are amazing things. We can use them to play games, to take professional-grade photos, to help us organise our day-to-day lives; we can use them to keep in touch and see the family members and friends we have been separated from because of the surreal events of 2020. By now, you’ll also be oh-so aware of their convenience in terms of being able to access pupils’ work, teach online and send emails. Whenever. You. Wish.

Perhaps the most ironic feature of all is how imperative they have become in our nighttime routine. We are using our devices to help us get to sleep at night when the constant pinging of emails, assignments and social notifications becomes too much. However, despite our best intentions, the buzzing of our phones leaves a buzzing in our brains long after we attempt to prise ourselves from the screen and try to sleep.

It is not only the neverending notifications that leave us unable to clock out. Our phones, tablets and computers release artificial blue light, which can stop the body from naturally releasing melatonin (the sleep-inducing hormone). In turn, this can interfere with the body’s natural internal clock that signals to us when it’s time to sleep and wake up (our circadian rhythm).

The more time teenagers spend on their phones, especially in the evening, the greater the delay in the release of melatonin, making sleep a challenge. They may struggle to fall asleep in the first place, but then they have difficulty staying asleep when they finally manage to nod off into a land that is (hopefully) free of Teams, Twitter and TikTok.

As a result, these teens sleep fewer hours. Over time, that sleep deprivation can lead to the symptoms of depression and anxiety.

So, is it poor sleep that is having an impact on teenagers’ mental health? Or is it teenagers’ mental health that is having an impact on their sleep? The cyclical and perpetual nature of both of these mean we may never truly find an answer, but it is impossible to ignore the impact of both.

We need sleep to be able to function day to day; we need it to heal the emotional and physical stress that is part of the human experience, and we need it to be able to process and put to bed the onslaught of information and interactions we encounter every day.

Teenage mental health is at breaking point and, with sleep playing a key part in our teenagers’ ability to regulate emotions and make decisions, we can’t afford to press the snooze button on its importance any longer. Sleep deprivation causes heightened feelings of anxiety and depression, and it is these feelings that are leaving our teenagers (and ourselves) staring at the ceiling or into the screaming blue light of our phones for reassurance. And so the cycle continues, as they sleepwalk into another day of exhaustion.

Robyn McLaren is a teacher of English, based in Scotland, and is studying for an MSc in mental health and education

This article originally appeared in the 1 January 2021 issue under the headline “We need to wake up to teenage sleep problems”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters