- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Primary

- Why I ditched the school spelling test

Why I ditched the school spelling test

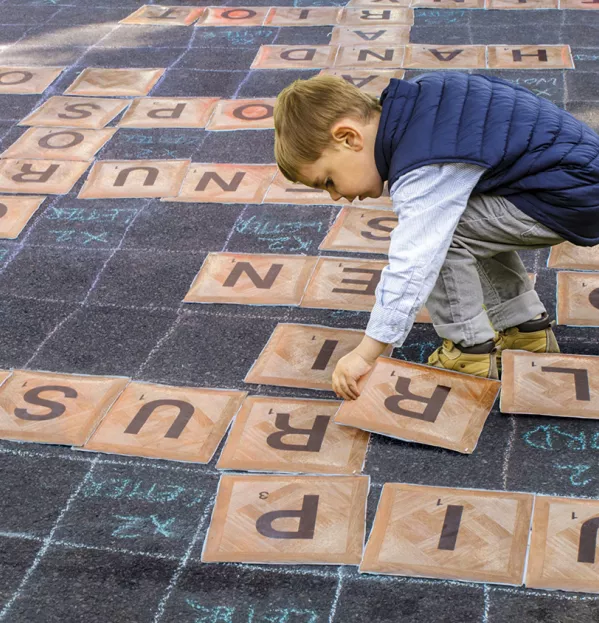

The approach that most schools take to spelling has been the same for generations: a list of words given to pupils to take home, memorise and regurgitate on test day. But is this really the best way to foster a love of language and explore the rich, complex world of words? Ann Jago thinks not. She decided to rip up the (spelling) rule book and start again. Tes asked her about her unique approach.

Tes: Spelling is traditionally taught through rote learning but you saw problems with this approach. What were the issues?

Ann Jago: Teaching spelling through rote learning lists of words meant that success on the test was arguably linked to the amount of effort put in by parents and carers rather than the child. Most of the learning took place away from school, with a weekly list sent home in the pupils’ bags, and there did seem to be a disparity between those children whose parents were able to assist with daily spelling practice and others whose parents were not in a position to ensure such rigour.

In particular, children with special educational needs and disability (SEND), for whom spelling practice was often challenging, seemed particularly at risk. In addition to this, the learning outcomes for the pupils were difficult to discern. They did not appear to be transferring their spelling-list knowledge to independent writing, which made me question the efficacy of the approach. When asked, the children said they learned the spellings for the test, evidently viewing the activity as an isolated objective.

Another issue was that, in a classroom with differentiated groups and lists of spellings, I would be standing at the front, administering lists A, B and C contemporaneously, expecting list-C children to be able to focus amid the delivery of different spellings to the two other groups. The very children who needed to sound out and concentrate were being hindered. Furthermore, I found that if I read the list in a different order, cries of unfairness would ensue and results would fall because the students had learned them in a particular order.

The futility of the exercise was confirmed to me when, on a wet and windy afternoon, at the end of the official weekly spelling test, two 10/10 Year 3 pupils (who had studied the sound “ai” for the test) were asked to spell “contain” (which did not appear on the list), and both independently wrote “contan”. It was time to consider the alternatives.

How did your search go?

I began to research the market, looking for off-the-shelf alternatives, but the programmes available were often linked to other resources or were prohibitively expensive. And these methods still largely relied on the dreaded list. At first, I adopted a rule-based approach: rather than a prescribed list, I would arm the children with specific spelling rules that they would be able to apply in their own writing.

However, the use of international phonetic alphabets - such as (/i:/) and (//) representing ea; (/:/) and (//) for er - and lack of familiarity with traditional spelling rules among non-specialist staff created significant barriers to confidence in delivery of the programme.

The rules were cumbersome, required constant repetition and led to moans whenever the word “spelling” was mentioned, sparking loathing rather than a love of language. And, ultimately, this approach still relied on rote learning without context.

I flirted with the idea of themed spellings to match the topic for that week, which seemed to provide the context that was needed but, ultimately, did not release us from the rote learning. I looked at alternatives internationally and, in particular, the spelling-bee approach in the US, but it didn’t fit with my idea of inclusivity - how would my dyslexic students cope? Was it not tantamount to ritual humiliation? Was this really the answer for 21st-century education?

As part of my research, I found that in agglutinative/phonetic-based languages, such as Finnish, there are few diagnosed dyslexic children. This led me to believe that phonics should play a role in any programme adopted.

So, what was the approach you devised?

I set about clarifying what it was that I wanted to achieve: happy, engaged students who enjoyed words, had a fascination for language and an interest in spelling. I devised a three-part lesson to replace the traditional test.

The first element was a “word of the week”: one word, studied in depth. We would write it, play games with it, learn the etymology, think about word families, word class and syllables, use our knowledge of phonics, use our best handwriting, and contextualise it with practice and application. I decided I would choose unfamiliar words to extend vocabulary for all.

The next part was an approach to high-frequency/tricky/red words: I decided to use dictation of a short sentence. For the higher-ability students, the whole sentence is marked; for the lower-ability, the focus word alone is marked, avoiding the masses of photocopying, whereby teachers or teaching assistants had previously had to print three to four separate spelling lists, sort and deliver them to the children - and replace them when they mysteriously vanished.

And finally, spelling patterns: rather than a list generated randomly by the teacher, the children focus on a pattern, directed by the teacher; for example, words ending in “-tion”. We troubleshoot by highlighting exceptions to the rule (like “-ssion”, or “-sion” ) and common misspellings, such as “-shun”. There is no formal test, although the pattern often forms part of a recap or plenary the following week.

What has been the impact so far?

When I first announced the abolition of the test to the children, there was an audible gasp and a few cheers. I explained the reasoning for the change and the new requirements.

This week, a child with SEND stood at the front of the class spelling “gingerly” and “reluctantly” in spelling-bee fashion - it turns out that they love that game.

With a kind and supportive environment, everyone wants to have a go at the front of the class. And in their writing, there’s less fear and more interest in words.

Would this approach work in any context?

I would say absolutely give it a whirl, have courage and follow your instinct. Each cohort will need a slightly different approach and I am fortunate that my headteacher has been fully supportive throughout. Testing and rote learning have their place, but the ritual of the list can be replaced.

Ann Jago is head of English and a Year 6 form teacher at Greenfield School in Surrey

This article originally appeared in the 19 February 2021 issue under the headline “How I...ditched the spelling test”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article