Will Curriculum for Excellence stage a comeback?

First, the rush of joy that comes with discovery. Then, the growing disenchantment as the thrillingly new becomes stale and predictable. Finally, just when you’ve all but forgotten that initial excitement, the comeback: the rediscovery of those old thrills, recast imaginatively for the times we’re in now.

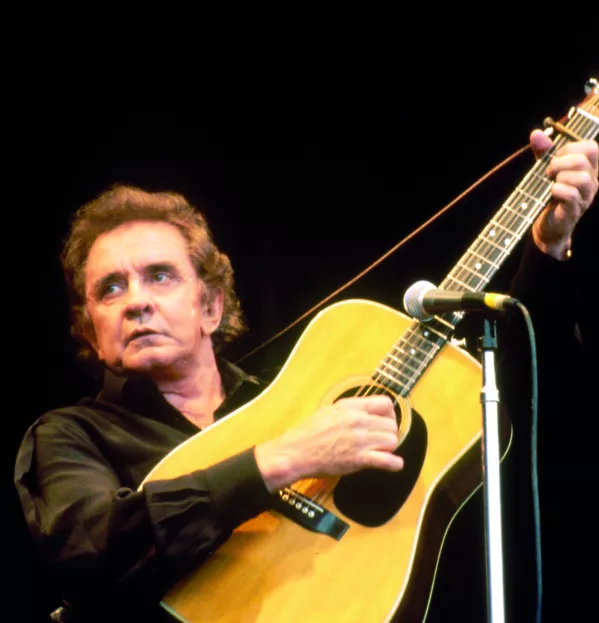

I could be referring to any number of music careers, but, perhaps more than any other, it is Johnny Cash whose life and work followed that trajectory. This 1950s pioneer, bursting out of Sun Studio in Memphis as part of the “Million Dollar Quartet” - alongside Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins - became a totem of modern country music who transcended narrow genre boundaries.

By the 1970s and 1980s, however, Cash was a tired symbol of a bygone era, trotting out tired versions of gospel standards and occasionally popping up in TV programmes like Little House on the Prairie.

Then, in the 1990s, Rick Rubin - an influential young producer better known for working with edgy rap and heavy metal acts - showed an interest in reviving this faded icon. Rubin took Cash’s old outlaw image and unique gravelly voice and fashioned a new sound. In 1994, the same year as his first album with Rubin, Cash made one of the all-time great appearances at Glastonbury: this stuffy old artist had become thrillingly current once again.

It’s not a comparison I ever thought I’d make, but in the past fortnight Curriculum for Excellence has made me think of Johnny Cash: CfE has had lofty peaks and deep troughs, much his like career, although we don’t yet know how this story ends.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about speaking to a headteacher who praised CfE effusively and the freedom it gave her. It had struck me that I was hearing comments like this far less frequently than I used to (“Let’s return to the high ideals that sparked a ‘national conversation’”, 8 February). The end of that piece seemed to strike a chord: the idea that, for all CfE’s shortcomings in practice, the ideals underpinning it - conceived way back in 2002 - are still as valuable as ever.

There was lots of reaction online, including blogs in response. Isabelle Boyd, a former secondary head and council assistant chief executive, was nostalgic for a time when “we were bold” and schools “ripped up the traditional timetable” to make room for innovation. Rod Grant, a headteacher in the independent sector, lamented that the reality of CfE had too often “killed the learning process”: excessive demands on teachers for evidence of learning had reduced the chances of ever providing the “personalisation, breadth and choice” that CfE had promised.

The overall mood online, however, was not one of despondence and fatalism: there were rallying calls to cast aside the fog of CfE in 2019 and take fresh inspiration from the high-minded ideals that brought it into existence in the first place.

Of course, we shouldn’t be Pollyanna-ish about this: there is little cause for excessive optimism. These are different times financially, when councils across Scotland, their budgets squeezed like never before in recent memory, are more concerned with cost-cutting than mulling over idealistic visions of curricular reform. The architects of CfE did not envisage council officials thinking it reasonable to propose scrapping music services or effectively doing away with Advanced Highers - just two of the numerous eyebrow-raising ideas that have been doing the rounds in recent weeks.

We are now, perhaps, in the third act of CfE: after the initial excitement, then the slow descent into a fug of confusion and bureaucracy, comes one of two eventualities: terminal decline - or an unlikely revival.

It does, however, beg an obvious question: who will be the Rick Rubin of Curriculum for Excellence?

@Henry_Hepburn

This article originally appeared in the 22 February 2019 issue under the headline “Can Curriculum for Excellence Cash in on a surprise comeback?”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters