- Home

- Leadership

- Finance

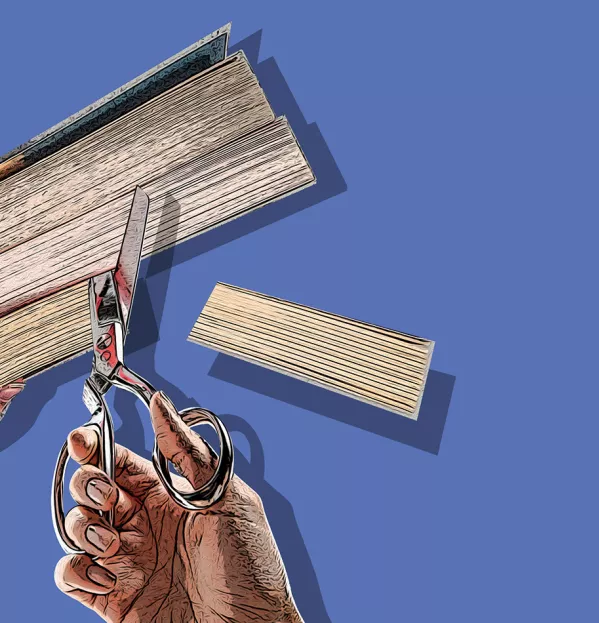

- What happens if your school runs out of money?

What happens if your school runs out of money?

The term “budget deficit” is the stuff of anxiety dreams for school leaders, mostly because of the unpleasant choices that inevitably come with it, such as: what should you cut first?

Do you choose not to renew the contract of a teaching assistant supporting children who have special educational needs or disabilities (SEND) but haven’t been granted funding? Cut the range of courses offered to students? Abandon that small group intervention for pupils falling behind on their maths?

No school leader wants to make these choices, and yet the evidence suggests that more and more of them are having to do so. A recent survey by the NAHT school leaders’ union found that 26 per cent of leaders were predicting a budget deficit in 2021-22, up from 18 per cent in 2020-21.

Why the increase? James Bowen, NAHT director of policy and a former headteacher, says that pre-existing “systemic, long-term underfunding issues” have combined with “some real acute pressures as a result of Covid in the past 18 months”.

Together, these two factors are leading to huge concerns about schools’ long-term financial futures, as highlighted in the National Governance Association’s annual survey, which this year showed that 56 per cent of respondents on governing boards did not think their school or trust was “sufficiently funded to deliver its vision to meet the needs of all pupils”.

Covid and the school funding crisis

“That’s what’s worrying us from our survey data: a suggestion that over the next few years, schools will be running on fumes,” says Steve Edmonds, NGA director of advice and guidance. He adds that the NGA has heard anecdotally and in surveys “that too many governing boards have found themselves on … a cliff edge, where all sensible efficiency savings have been made”.

“So, they are in that position of having to look at a bailout, if you like, from their local authority [LA] or from the ESFA [Education and Skills Funding Agency, which regulates academies],” Edmonds continues.

Given that these financial pressures on schools are growing and widespread, it’s important to ask: what do school leaders need to know about leading a school when money runs low - or runs out completely?

According to Bowen, leaders essentially have two choices: “You have to make cuts or you are starting to look at a deficit position.”

In terms of how to start making cuts, once schools have disposed of obvious “luxuries” such as funded school trips, another option is to reduce the length of the school day - for example, by dropping from six periods to five or closing early on a Friday. But this has a curriculum impact, says Edmonds, often leading schools to “restrict their curriculum ambition [and] offer less of a broad and balanced curriculum”.

For any major cost cutting, though, there’s really only one place to look: staff costs. School leaders whom Tes spoke to for this article put staff costs at anywhere between 70 and 90 per cent of their spending.

When it comes to school staffing, every class has to have a teacher in it, so teaching assistants are often the first to lose their jobs in any restructuring. But that comes with an educational cost, given the role that TAs have in supporting children with SEND.

“The reality is that if you have fewer teaching assistants, that’s fewer pupils with SEND who get the support they need,” says Bowen. “And it means leaders having to ration that support and make really difficult choices about which children get support and which don’t.”

One cost-cutting option might be to let fixed-term contracts expire for TAs and not replace them. However, that might mean the remaining TAs get moved across to solely support children with funded SEND requirements or to class cover roles, says Michael Tidd, headteacher at East Preston Junior School, in West Sussex - and, again, pupils are the ones who suffer from that.

“As a result, it’s often those pupils who are on the SEND register but don’t have a statutory education, health and care plan [and attached funding] that lose out, because schools don’t have the capacity for additional support,” says Tidd.

Cutting costs usually means that schools have to make some major compromises on the quality of their provision, then. But if leaders do not make those cuts (or if making them proves simply not to be enough), that leaves only one option: running a deficit.

This, of course, comes with its own implications. Running a small deficit one year and covering it from reserves before returning to surplus the following year is one thing; longer-term or larger deficits are another.

So, what does a significant deficit mean for a school?

For LA-maintained schools, the rules “essentially allow local authorities to balance the books of all the schools under their control”, meaning they can claw back money from schools in surplus and agree with an individual school a “recoverable deficit” to be repaid to the local authority, says Julia Harnden, funding specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders.

The Department for Education sets out guidance for what should be included in a local authority’s rules around this, including that there should be “a provision that makes it clear that the local authority cannot write off the deficit balance of any school”.

So, having a deficit is “a bit like sitting on a massive overdraft and knowing you have got to pay it back [to the local authority] within a certain period of time”, says Bowen.

Meanwhile, academy trusts “are required to set out and approve a balanced budget”, says Harnden. “If they are unable to balance potential deficits using funds brought forward from the previous year, they would be in breach of their funding agreement and this can result in intervention by the ESFA.”

The DfE also has specific guidance on deficit recovery for academy trusts and, as the DfE can be more “hands on” with academies than with LA-maintained schools, this guidance is accordingly more detailed.

If there’s a deficit at overall academy trust level, the DfE warns that “where there is no LA acting as ‘banker of last resort’, no ability to borrow and where budgets acutely reflect financial and operational viability, successive deficits will consume cash, and ultimately could lead to insolvency”.

However, if one academy within a multi-academy trust is in deficit but the MAT breaks even overall, that’s usually something for the MAT to address through its pooled resources without ESFA intervention, the guidance explains (although persistent deficits in any individual school within a trust “should not be neglected”, it adds).

Rebecca Boomer-Clark is chief executive of Academies Enterprise Trust, one of England’s largest academy trusts, and a former regional schools commissioner for the South West. She stresses the importance of taking a multi-year view when thinking about schools in a trust with structural deficits to address. For example, she says, educational recovery after the pandemic is a “multi-year challenge”, and a solution like cutting teaching staff numbers will be too short-term if local demographic trends will soon bring an increase in pupil numbers.

“The reality is that some larger multi-academy trusts can carry some of that across a multi-year view,” says Boomer-Clark. “But [for] standalone schools … [and] small multi-academy trusts, that’s much more challenging.”

For both LA-maintained schools and academy trusts, going into significant deficit will mean agreeing a recovery plan with the local authority or the ESFA. This would usually involve a school committing, in quite a high level of financial detail, to how it will achieve a balanced budget within a relatively short period, usually three years.

The DfE’s guidance explains that maintained schools must submit a recovery plan to the local authority if their deficit rises above 5 per cent of income at 31 March of any year.

As to what a recovery plan means in practice, the “practical options” in the DfE guidance for academy trusts on recovering deficits could offer some indication of how LA-maintained schools might have to cut their costs, too.

Any deficit recovery plan “that does not start with consideration of salary costs is not a serious one,” the DfE says. “Trustees must challenge the assumption that salary costs are fixed.”

Options outlined include introducing a moratorium on recruitment and reducing staff costs through “natural wastage” ; moving to “internal promotion of lower-paid staff rather than recruiting more expensive teachers” ; reviewing “use of any surplus staffing including non-contact times” ; reviewing teaching and learning responsibility (TLR) allowances; and looking at “redeployment in areas with potential surplus staff (classroom support could be reviewed enabling redistribution of duties and hours)”.

Beyond this core area of staff costs, the DfE guidance has some further suggestions, ranging from the marginal (“would it really matter if the painting programme was deferred a year?” ) to moves that potentially hit the poorest parents (“it is easy to lose track of parental debt especially in relation to school lunches”).

The option of a recovery plan will, of course, bring some very intensive scrutiny of school or trust leadership from a local authority or the ESFA - there will be a lot of difficult meetings (the DfE’s guidance for academy trusts talks about the possibility of “weekly monitoring” if a deficit is close to exhausting a trust’s reserves). So, this is no easy solution. In fact, it brings a huge amount of extra work.

And what if a recovery plan doesn’t work and a school or trust still can’t escape the cycle of deficits? For a LA-maintained school, a council “would look at a structural solution for that school”, says Edmonds, who is a former governor services manager at Birmingham City Council who oversaw the giving of advice and guidance to maintained schools and academies.

“That might mean closure … [and] extending provision at a neighbouring school to absorb those pupils,” he continues. “If it was a trust, the ESFA and the department would look very closely at the viability of the trust and the schools within it. One possible outcome could be rebrokering those schools and seeing them go and join another family of schools and another trust.”

In his time in local authorities, Edmonds worked with schools facing financial challenges and went through structural changes with them that created a sustainable in-year budget, but “we still had the challenge of paying off the deficit repayment plan … During that process, there have been serious conversations about the long-term future of the school”.

But there are, of course, steps schools can take to avert such bleak scenarios. Boomer-Clark suggests that there are things that school leaders can manage that will gradually improve their school’s financial outlook.

For example, the size of a leadership team and having a “reasonable” TLR structure in relation to the size of a school can have an impact on costs.

“Fundamentally, the economics of schools are quite straightforward. If you’ve got enough pupils, even with the variability in funding nationally - and the contingent equity issues that raises - there’s always a way you can manage to make it viable,” she says.

Cathie Paine, deputy chief executive of REAch2 Academy Trust, agrees that pupil numbers are of crucial importance.

“With staff costs rightly being the single largest item in any school budget, and a progressive pay system, schools need to be single minded in their focus on pupil recruitment so that today’s commitments continue to be affordable in the short-to-medium term, and to avoid any unnecessary restructuring in the future,” she says.

The situation is not hopeless, then. But there’s an argument that, ultimately, however carefully schools manage their staff costs and pupil numbers, the financial breathing space to properly serve all their pupils will only come with proper funding - and here, school leaders have some clear calls for targeted investment.

There are “certain things that need to be funded properly: education recovery, early years and the increasing pressures around child and adolescent mental health,” says Boomer-Clark.

Meanwhile, in the NGA’s survey of governing board members, the cost of supporting high-needs pupils and those with SEND was identified second in the top five challenges for boards in setting a balanced budget, after overall staff costs.

Bowen, too, flags SEND as a funding priority: “We think the current SEND funding is woefully inadequate,” he explains. “A lot of the pressure on school budgets comes from the SEND funding crisis.”

There is “a lot of SEND need that has not been formally diagnosed” and resourced, adds Boomer-Clark, “and that’s placing huge pressure on schools”.

The DfE promised a SEND review in 2019, but has missed multiple deadlines it set itself to publish that review. This is a real problem, says Edmonds, given that the underfunding of SEND “does have a real bearing on future funding of our system”.

“We would be asking the new secretary of state to use his influence to get that review published and give us a roadmap for high-needs funding that is so desperately needed,” he says.

However, tackling the issue of SEND underfunding alone will not be enough; that fits within a broader picture of underfunding of other services provided by local authorities, whose funding from central government has been slashed since 2010.

“One of the greatest challenges we find is balancing the need to minimise our own costs with the need to fill the gaps in other services, whether that’s through providing a food bank, supporting young people’s mental health or providing support for pupils with special educational needs for whom there is no available place in special education,” says Tidd.

Michael Merrick, who leads two primary schools in Cumbria, agrees that while the cost of supporting the “broken” SEND system “leaves budgets very vulnerable”, schools are simultaneously having to support parents who “are themselves in crisis”.

“I don’t know if it’s nationwide but I would argue that here, social services are on their knees … When [social services] sneeze, schools catch a cold because we are having to deal with those issues now,” he says.

But at the same time there is a “contradictory pull” from government stressing the need to prioritise educational recovery and talking about the return of assessment, adds Merrick.

“When you’ve got very little left in the budget, you’ve got quite a stark choice between what [the government] wants the focus to be, which is the academic and the curricular, and what the focus does really need to be, which is the health and wellbeing of your community,” he explains.

So, what does that all mean for schools’ financial outlook this year and beyond? Harnden sums up the challenge that many leaders are now facing: “Many schools have a perpetual tightrope to walk in order to achieve financial stability, working within budgets that have been consistently under pressure for the past decade owing to inadequate government funding.

“Leaders need to be experts in proactively planning ahead, building in challenging scenarios to avoid being caught out by circumstances that could have been predicted. The key is for school leaders to understand their financial situation at all times and plan ahead.”

But, given the scale of the SEND and social services crises and their impact on school budgets, there’s an argument that if schools are going to be papering over the cracks left by government underfunding, leaders ought to do so while collectively letting the government and public know exactly what cracks are emerging.

“Part of the solution is not even necessarily about schools; it’s about supporting SEND provision, alternative provision, children’s services,” says Merrick. “If you don’t want to do that, then schools need to be given some sort of uplift to be able to increase their capacity around SEND and wellbeing and welfare … Ultimately, you can’t deliver a quality curriculum if your whole focus is on trying, at breaking point, to support all of these needs, which are beyond the capacity of the school.”

While all school leaders will aim to control their spending as effectively as they can, there are costs left by systemic education underfunding, by Covid and by the crisis in SEND and wider public services that no adept budget management by any individual school will be able to dispel; the solution to that can only come from government.

John Morgan is a freelance journalist

This article originally appeared in the 3 December 2021 issue under the headline “What if your school runs out of money?”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters