- Home

- Leadership

- Staff Management

- The primary subject leadership problem - and how we fixed it

The primary subject leadership problem - and how we fixed it

“I remember being told, ‘you’re going to be leading PE’. I didn’t know how to lead PE. I didn’t know the curriculum or how to give feedback. So I had to teach myself.”

Dan Sandy is school improvement adviser at the nine-school Lighthouse Federation, the largest federation (in which two or more schools operate under a single governing body) in the country. He explains that his experience of becoming that PE subject leader in primary school some 20 years ago was incredibly challenging and stressful - not least having to give feedback to more experienced staff members.

“I watched the PE lesson of a senior member of staff and the lesson required a lot of development. I thought ‘I don’t know how to do this’. I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. It was really challenging.”

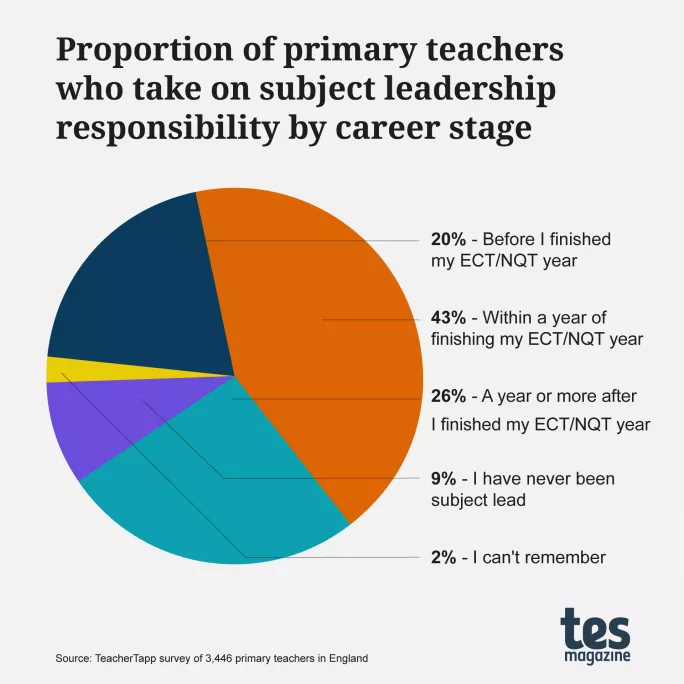

Being thrown in at the deep end as a subject lead in primary school is common. A recent TeacherTapp survey, commissioned by Tes, found that 63 per cent of the 3,446 primary teachers questioned took on subject leadership responsibilities either during their early career training (ECT) or within a year of finishing it.

Sandy says this reality means teachers often have to “muddle along”, struggling with a host of new responsibilities they are not equipped for.

“There’s nothing out there to support primary subject leaders,” he adds.

It’s an issue the federation’s chief operating officer Paul Drew says he recognises, too: “There are 23-year-olds just coming off their ECT courses having to give feedback to teachers who may be 10 years their senior, and have never done anything like this.”

Subject leadership skills

Drew admits he always accepted this as the norm until he had a moment of clarity while on a family holiday in Disneyland.

“I was in a queue for a ride and got chatting with one of the workers who was there making sure everyone was OK. He explained they were on a Disney leadership programme that helped develop them as future leaders. It made me realise that’s what we needed.”

From this, Drew tasked Sandy with creating a leadership course for new post-ECT teachers who were taking on subject leadership responsibility, so they could manage the step up - something that aligned with a master’s in education that Sandy was undertaking and that required a dissertation project.

So at the start of 2024, Sandy began work on creating, implementing and evaluating an eight-stage course whereby all teachers across the federation who complete their ECT move on to the Emerging Lighthouse Leadership Programme (ELLP).

This course has since seen two cohorts graduate, with a third due to start in the spring of next year. It takes place once every four weeks, with staff meeting at a central location for about three hours.

An eight-stage process

The course begins with a focus on communication, which Sandy says is to help staff understand the need to simplify and customise messages for colleagues so they are delivered in the right way.

“If you invest time in knowing your colleagues and understanding how they like to receive feedback, so that they’re then able to receive that feedback positively and act upon it, then it works better for everyone,” he explains.

Keen to show that many of these skills are not unique to teaching but are simply good management skills in general, the federation engages the help of outside speakers.

“We have a freelance TV presenter come in and explain about how she has to be communicating all the time between presenters, sound guys, the camera crew and so on, to show why the principles of simplifying and customising messages are so key.”

Time management is the focus of session two, while sessions three and four focus on emotional intelligence, which Sandy says requires two sessions owing to its importance.

“Research shows emotionally intelligent people are most likely to be successful in the workplace, and most likely to be promoted,” he notes.

“So we’ll look at what emotional intelligence is, and how to develop emotional intelligence as part of the leadership process. Then we look at things like body language, tone of voice, eye contact, and we watch videos from FBI agents on how to read people and so on.”

Transferable skills

Session five is about problem solving and resilience, and again an outside speaker is used, with a former close-protection officer who has worked with high-profile sports teams coming in to talk about how to be resilient in the face of problems, especially if you don’t have an immediate answer.

Drew says the use of outside experts is important because they want staff to recognise that many of the skills they are learning will stand them in good stead throughout their careers.

“Leadership is transferable across industries and we want our emerging leaders to recognise that. Having a session led by someone from a different sector, rather than just another educational leader, helps,” he says.

“We’re getting them ready and being able to manage their subject - but we’re getting them prepared for a middle leadership role or senior leadership role, too.”

Session six of the ELLP sees participants visiting lessons with a school leader mentor who they collaborate with to write feedback about a lesson, and then the trainee observes the mentor delivering that feedback, taking note of how the leadership skills discussed are used.

In session seven, the roles are reversed, with the participant observing the lesson alongside the school leader, but this time they give the feedback, with the mentor offering support and guidance.

In the final session, all participants come together to share their experiences of lesson visits, feedback and application of leadership skills.

Broadening access

So far, 17 teachers have been through this process, with another cohort set to start in the spring. Sandy says the transformation among participants has been clear to see.

“For the dissertation, I had to be really rigorous with the evaluation process and from that the feedback was really positive. I did observations with participants on the pilot and saw them grow in confidence and their leadership styles develop.”

What’s more, other staff in the federation are keen to take part in something similar, with Drew confident this can be offered, with a few tweaks as required.

“I think the nuts and bolts of the course would stay the same, but obviously doing this course for a group of teachers in year five or six of their career would require some adaptation to how the course is structured.”

Filling a leadership gap

Is creating an entirely bespoke leadership course in-house really necessary though?

After all, there are plenty of leadership courses already out there, not least the National Professional Qualifications (NPQs) that come with government backing - so why not use those?

Sandy and Drew argue such courses do not meet the challenge of subject leadership at primary - and are often offered too late for those who would benefit most.

“My research found most people who do an NPQ only do so around nine years into their career, which is way too late,” Sandy says.

“And in terms of subjects, they only offer English and maths, so there is nothing there for any other subject, like music, PE, ICT, computing, geography, history - all key subjects that a primary subject lead has to look after.”

It’s for this reason that Drew and Sandy hope the work they have done to create a course for new primary subject leads will grab the government’s attention.

“This is a simple solution that will hugely impact recruitment and retention,” says Sandy, who notes it could especially help to stop newer teachers leaving the profession.

“I’ve seen people receive feedback that wasn’t thought out as [the person giving the feedback] didn’t know how to deliver it, and [the other teacher] found it crushing. I thought, ‘I don’t want to be a part of this’ - that’s what we can try and stop happening with this course.”

Drew says that a greater focus on subject leadership skills would not only help more teachers feel confident in the role but also ensure that a core purpose of that work - improving teaching across primary subjects - would have more of an impact.

“If we’ve got trained subject leaders, who know their craft and know what they’re doing and how to help others get better, that can only help improve what’s taking place in classrooms - and that will lead to better outcomes for children,” he says.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters