- Home

- Leadership

- Staff Management

- We need to teach our teachers about feminism

We need to teach our teachers about feminism

Feminism has been defined in popular internet memes as “the radical notion that women are people”. Yet this movement for the liberation of girls and women is still misunderstood. Indeed, studies have shown that many teenage girls are keen to distance themselves from feminism because they perceive it as “man-hating” and “ugly” (as Danielle Giffort noted in her 2011 essay “Show or tell? Feminist dilemmas and implicit feminism at girls’ rock camp”).

In 2021, there are still a range of gender injustices that affect mostly girls but also boys. If teachers had a better understanding of feminism and gender issues, we would cultivate an environment of greater protection and inclusion in our schools - to the benefit of all pupils.

There is a common misperception that we are now living in a gender-equal utopia, where girls can have it all and there is no need for “man-hating” feminism. However, there is a plethora of worrying evidence that schools in the UK still have a long way to go in terms of gender equality or, indeed, safety for girls. It is important for teachers to be properly educated on feminism and toxic masculinity to ensure that our schools are places where all children can thrive.

My own experience is that teacher education on gender is far from adequate. As part of a recent master’s assignment, I was given the task of finding out whether I have a “male or female brain”. While the task was intended to make me consider “learning styles”, I was astounded to find such thoroughly debunked pseudoscience on a course for educators. While I recall some excellent university sessions on LGBT inclusion during my initial teacher training, I do not recall very much on gender. Not training teachers to recognise misogyny and toxic masculinity is simply not good enough.

In a 2019 book on early childhood socialisation, Boys Will Be Boys: Power, patriarchy and the toxic bonds of mateship, feminist author Clementine Ford notes that “girls are expected to be pretty and delicate, boys are supposed to dominate”. Even very young girls notice the male domination of what is supposed to be a playground for all. Perceived male superiority and dominion is what feminists refer to as patriarchy.

Early experiences of patriarchy often involve playground football and the toxic learned behaviour associated with the sport. Ford argues that patriarchy also harms boys, especially those who do not fit into the “typical boy” mould. Indeed, accusations of femininity are used to punish boys who run, fight or kick “like a girl” - the subliminal message being that femininity is weak and inferior. Young girls also take notice when staff ask for “strong boys” to help with jobs around the school: boys are strong and boys get out of class to go on adventures. These early experiences become embedded in the psyche and teach girls their place in society.

For young people in secondary schools, the effects of patriarchal structures become even more damaging and stifling. Jessica Taylor, in her 2020 book, Why Women Are Blamed for Everything, argues that schools put girls at risk of sexual violence by the perpetuation of “victim-blaming culture”. This is the age-old mentality of “why was she walking alone/dressed like that?” that removes focus from the perpetrators of violence, and burdens girls and women with it instead. This happens in many ways, from schoolgirls being given strict dress codes to not having their reports of sexual harassment taken seriously. And sexual harassment is something that very much happens in our schools. Taylor cites Westminster’s Women and Equalities Committee, which, in 2016, reported that 59 per cent of girls had been subject to sexual harassment in school.

The same committee noted that sexual health and relationships education normalised victim blaming by showing girls a film in which a sexual assault was implied to be a result of the girl’s lack of care. No equivalent films were shown to boys to educate them on their behaviour and responsibilities.

‘A distraction for boys’

I am in the early stages of interviewing girls in Scotland in an attempt to find out about their experiences in school. So far, many statements are consistent with the above. Girls have told me that their teachers are very explicit on what they can and cannot wear on non-uniform days in a way that they are not with boys (meanwhile boys are allowed to be topless in PE with no comments made from their teachers). Girls tell me that the reason they are not allowed to wear straps that are “too thin” is “in case we distract boys”. Furthermore, girls report being chastised by male teachers over their skirt length. This is in stark contrast with the case of a West London Muslim girl who, as reported in January this year, was excluded from school for her skirt being “too long”.

Girls it seems, cannot win and they know how much easier life is (in many ways) for boys. From a feminist perspective, these girls are being sent the message that they are responsible for male behaviour. Conversely, boys are learning that girls are responsible for their behaviour, not themselves.

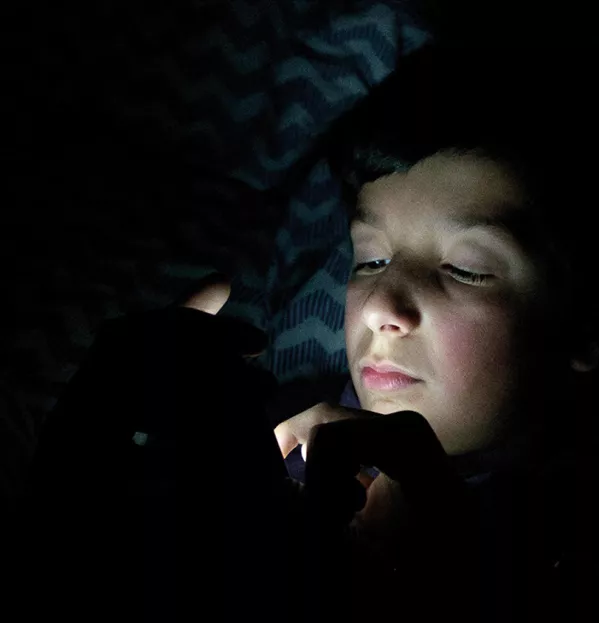

Girls have also reported a lack of equity in several curricular areas. Many feel less able to fully participate in physical education as a result of being laughed at and insulted by boys, and this behaviour is being accepted as normal and going unchallenged by teachers. PE is often another place where girl’s clothing is policed and they must ensure that their shorts aren’t “too short”. In wider society, girls (arguably more so than boys) are subject to a bombardment of advertising and social media that tells them that the way they look isn’t good enough and “detox” teas or expensive make-up are the cures.

Girls - should it need to be said - aren’t just shallow creatures who are obsessed by appearance. And yet, a girl learns from a young age that her value, opportunities and social standing lie in her appearance. If participation in PE will ruin a girl’s psychological and social safety, that becomes a barrier to her education.

Girls notice a lack of encouragement in traditionally “male” subjects, such as technology, and they see boys dominating teacher time and attention in other subjects. Girls observe a teacher bias towards “funny boys” and “class clowns”, who dominate lessons and teacher attention. This mirrors findings from a study in Canada - see Shauna Pomerantz and Rebecca Raby’s 2013 article, Smart girls: Success, school and the myth of post-feminism - that domineering boys were seen to benefit from “special relationships” with teachers that girls did not have. Girls I have interviewed are also aware of the gender pay gap and expect to be faced with fewer career and financial opportunities than their male counterparts in later life. And why wouldn’t they be acutely aware of this reality, if they cannot even have equity and safety in the school environment?

Another issue that has arisen in my interviews with girls is their education (or lack of) on abortion. Girls report that they are given “one-sided” information on abortion and told that it is “just wrong”. One girl said: “I know it’s a Catholic school but I think they should teach us about both sides of the story.” The least that young women deserve in 2021 are some facts and balance. For example, when there is no access to safe abortion, many women and girls resort to unsafe procedures, as the World Health Organization (WHO) documented in 2020. The WHO further estimates that 7 million women a year end up in hospital as a result of unsafe abortion complications. How can it be deemed “education” to instil shame and stigma into schoolgirls over their bodily autonomy? Why are they not learning that restrictive laws do not stop abortion, they only make it dangerous?

However, despite an acute awareness of the injustices they face, girls also report that there are things in school that are unfair on boys, such as a lack of “emotional support” and the pressure to be a “real boy”.

Unique position

There is no doubt that the cultural climates in some schools can range from damaging to downright dangerous to both girls and boys. The way to tackle this is to ensure adequate training on gender issues for all teachers and give us the tools to critique school culture through a feminist lens. Feminist ideology also benefits boys who are stifled, stunted and harmed by patriarchy. Teachers are in a unique position to influence the social structures of their schools. The burdens of assault, toxic masculinity and sexism cannot fall on the shoulders of schoolgirls. It is essential that they have the full support and allyship of their teachers; teachers who are educated and conscious of their own behaviours and attitudes, and the invisible structures of oppression that we can either reinforce or help to dismantle. It is as important for male and female teachers to be properly educated in the same way. Women can both internalise and perpetuate misogyny. In fact, a scroll through the Facebook comments section on a recent news report about an assault on a teenage girl in Glasgow showed several men and women questioning the girl’s movements rather than her attacker’s actions.

My own feminist education did not begin until well after my initial teacher training, when a book by a feminist author caught my eye in Waterstones. Further reading has taken me down a rabbit hole and brought the realisation that children, particularly girls, are being failed in schools every day. Where are the continuing professional development sessions on toxic masculinity or victim blaming? Above all, where is the education for children? One box-ticking session on the Suffragettes on International Women’s Day is not enough. Gender oppression is not just something that happens in “developing countries” where girls may struggle to access education - it happens right here.

Gemma Clark is a primary teacher and a master’s student, based in Scotland. She tweets @Gemma_clark14

This article originally appeared in the 2 April 2021 issue

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters