5 ways I apply the pedagogy of Paul Hollywood

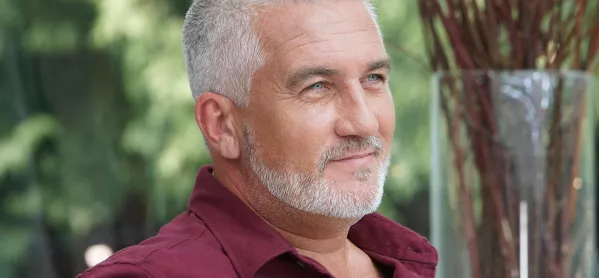

October, again. The long, hot days of summer fading into the distance. Months of cold and dreich on the way, punctuated by Hallowe’en discos and Christmas parties. Pupil reports are due, the nights grow darker, and with only Paul Hollywood’s brilliant blue eyes to bring us any cheer.

As another series of The Great British Bake Off dusts our weeknights with a little joy, my eyes are drawn, as always, towards Paul. The animal magnetism of him. The thoughtful, brutal way he chews on a teacake.

And like any reflective practitioner, I am always looking for models to help hone my classroom craft. In Paul Hollywood, in that tent, I observe a master at work - in five crucial ways.

How Paul Hollywood helps my teaching

1. Presence

This is a man entirely in control of his environment. Pacing the perimeters, marking his territory, the others merely passing through. It’s something I often do with younger classes, or when there are low-level behaviour issues: plot a route through the desks, stand in the back corners, make my voice a roving presence. If pupils expect to see you always standing in the same place - at the front - mix it up. Sometimes the way to deal with disruption is to become the disruptor. I see student teachers confined to a little stage near the board, and encourage them to take ownership of the room.

Great British Bake Off: ‘Bake Off winner had his first bake-off at our school’

Quick read: Five things teachers can learn from The Great British Bake Off

Baking in learning: How a Bake Off teacher uses cake in geography lessons

Bake Off judge: Schools must teach healthy cooking

2. Pace

What I particularly like about Hollywood’s approach to timing a challenge is how unrealistic he is. Partly this is to make good television - the melting ice creams, the unset meringues, the soggy bottoms. But there’s a sound theory behind this. He is trying to inspire excellence. And I think, in classrooms, a little bit of stress, a good pace, can be a wonderful thing to avoid complacency and ennui. If only I had Noel Fielding and Matt Lucas to bellow out timings to the pupils, while I ate a scone backstage. But in class, of course, timing and pacing is malleable - we can stretch it out.

3. Instructions

By far my favourite part of each episode is the weekly technical challenge, where Hollywood and fellow judge Prue Leith set bakers an unseen task, and provide only the most bare-bones instructions possible: “Make a choux pastry”, “bake until ready” and other undirected vagaries. I’d love to try this in class: “Children, write a sonnet! Analyse the role of Yorick in Hamlet! Prepare a dramatic monologue titled Modern Life is a Pantomime! You have 20 minutes.” I think, as a group activity, with lots of resources and supported scaffolding, this could work as an excellent piece of collaborative, student-led learning.

4. Praise

Paul Hollywood possesses, surely, the most powerful motivational tool known to modern society: the Hollywood Handshake. That strong, clammy embrace, which can reduce grown men and women to tears. And the beauty of this handshake lies in its rarity; the careful deliberation over when his thick, calloused fingers will be offered in congratulations. “Surely, now,” you can see the bakers think after birthing a successful souffle. “Surely, now I will be honoured with it.” Only to be left bereft, unshaken. There’s a clear lesson for teachers here - use praise that is not only sincere but meaningful.

5. Assessment feedback

Each episode ends with The Showstopper, a mad challenge with towering cake structures and ridiculous engineering expectations. The poor bakers sweat and swear and pour their soul into these creations. Once they are presented, Hollywood admires their work for about three seconds before slashing it to ribbons with a knife. Always attacking the fanciest bit first. Chewing over the flaws with glee, stabbing his big fat thumb in with a twist. And that’s what marking pupils’ work sometimes feels like - pulling apart what they have created, finding areas that need improvement as well as recognising success. To develop a growth mindset, we need to always think about new challenges.

Paul - I look forward to tuning in for another masterclass tonight.

Alan Gillespie is principal teacher of English at Fernhill School, in Glasgow. He tweets @afjgillespie and recently published his first novel, The Mash House

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article