It is not all “doom and gloom” when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), it can do “incredible things”, says Dr Mhairi Aitken, an expert on AI and children’s rights - including opening up new opportunities for children “in education and learning, and entertainment and having fun”.

For instance, in education, AI can convert text to speech for children with visual impairments or speech into text for the hearing impaired, she adds.

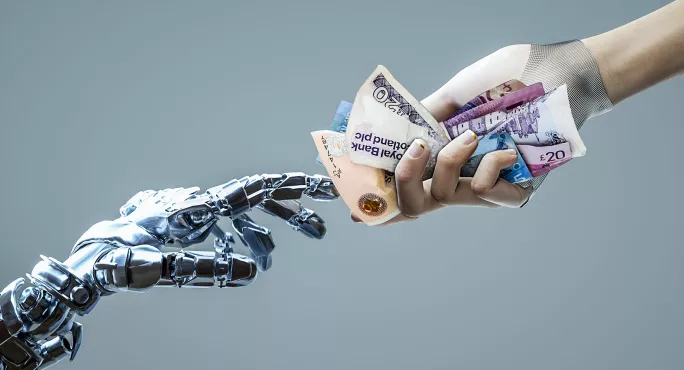

However, she warns that AI - which has been hitting the headlines because of rapid advances in generative AI and platforms such as ChatGPT - could also open up “new inequities in learning”, given the best systems are likely to come at a premium.

Dr Aitken, who is an ethics fellow at The Alan Turing Institute, the national institute for data science and AI, made her comments at the Children in Scotland Annual Conference in Edinburgh last week, as she took part in a panel discussion.

‘Real concern’ good AI will not be for all

She said: “As generative AI tools become more and more part of education, including education outside of the classroom and home learning, there’s real concern that having access to good, reliable generative AI systems, which will often be the paid-for systems, will not be accessible to all. That potentially creates new inequities in learning.”

There are often claims that generative AI could help address inequality, said Dr Aitken, by providing all pupils with opportunities to have personalised tutors or at-home learning experiences.

However, these are “increasingly paid-for experiences” and would only be available to those with reliable internet access and digital devices.

That generative AI could “potentially exacerbate existing inequalities” is “a really, really important consideration”.

Importance of involving children in decisions about AI

Dr Aitken also emphasised the importance of children being involved in decisions about how generative AI technologies are “designed, developed and deployed”, as well as regulated.

She explained that adults often use and experience technology differently. Assumptions about the way children use the same tools can lead to regulations and safeguards that are “inappropriate, ineffective or sometimes even harmful” if they do not “align with children’s actual experiences and needs”.

She said: “How many adults have grown up in a world of generative AI? Literally zero. Children are the only experts in growing up in a world of generative AI, so we need them in the room.”

Children more optimistic about AI

Also contributing to the discussion was Gregory Metcalfe, lead for the Children’s Parliament’s AI project looking at what children know about AI, how they feel about it and how they would like to see it used in the future.

The project published its first report last year and is being run with the Scottish AI Alliance and The Alan Turing Institute. It is working with 87 children in four primary schools in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Shetland and Stirling.

Mr Metcalfe said that children are generally more optimistic about AI and tend to focus on its positive uses. However, they share adults’ safety concerns and are keen that AI does not replace the relationships in their lives - including their teachers.

He added: “They really value the role that teachers play in understanding them as individuals and understanding their emotions and they are very aware that is not something that AI would ever be able to replicate.”

For the latest Scottish education news, analysis and features delivered directly to your inbox, sign up to Tes magazine’s The Week in Scotland newsletter