Demand soars for ‘emergency’ school improvement cash

There has been a surge in the amount of emergency cash given to multi-academy trusts (MATs) to help struggling schools, Tes can reveal.

The increase in handouts from the Department for Education’s Emergency School Improvement Fund (ESIF) has emerged as the government works on plans to change the way schools are supported, including by setting up regional improvement teams.

Leaders say Tes’ findings reveal the “hidden” and growing financial costs facing MATs that carry out improvement work, as the level of need grows.

And, amid government attempts to dampen expectations ahead of next month’s Budget, they warn that new regional teams will lack impact without sufficient resources.

Our analysis also reveals that most of the trusts awarded the funds go on to absorb the schools they help, suggesting the money gives MATs an advantage when it comes to growth.

Rise in money dished out under scheme

Trusts can apply for ESIF grants to deliver short-term support to schools facing “unexpected or imminent failure to improve” in areas such as leadership, governance, safeguarding, human resources and finance, according to DfE guidance.

Tes’ analysis of government figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act reveals that, between April and June this year, the DfE had already received 40 applications for ESIF grants - close to the number received over the entire 2023-24 financial year.

The DfE confirmed that bids are “demand-led” and are usually received throughout the year, rather than being front-loaded.

Although applications are not always considered or awarded in the same financial year in which they are received, the overall number and value of awards appear to be rising in recent years.

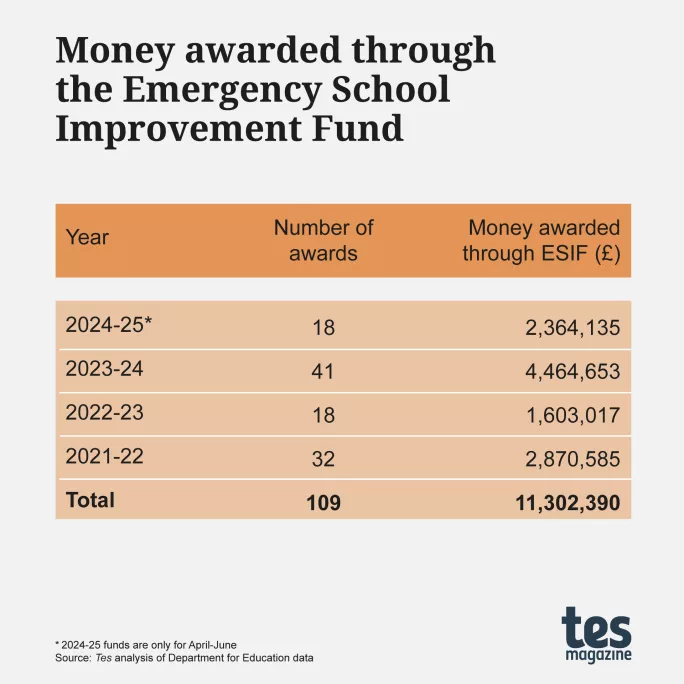

In the year from April 2021, the DfE handed out nearly £2.9 million of ESIF cash across 32 separate awards.

This figure fell the next year, to £1.6 million shared across 18 grants, but the number of awards then more than doubled to 41 in 2023-24, amounting to almost £4.5 million.

Between 2021-22 and 2023-24, there was a 56 per cent leap in the amount of ESIF cash handed out, against a 28 per cent rise in the number of awards granted.

Overall, between 2021 and 2025, more than £11 million has been awarded to trusts through the ESIF grant.

- Exclusive: Trust capacity grants fall £33m short of bids

- Revealed: The fastest growing MATs

- Exclusive: 9 in 10 large MATs expect to grow by 2025

Jonny Uttley, CEO of The Education Alliance, said the rise could be a reflection “of worsening finances in that period and more trusts needing funding with doing support work prior to conversion”.

Trust to school support has sometimes “operated a bit on goodwill”, he said.

Nearly nine in 10 (86 per cent) of the 91 ESIF applications between 2021 and 2024 were accepted, DfE data obtained under FOI by Tes shows.

Responding to Tes’ figures, Warren Carratt, CEO of Nexus Multi-Academy Trust, which has 16 schools, said: “What this tells us is that there is a hidden financial cost to improvement activity from the MAT sector over the last couple of years.”

He had been unaware of the grant until now.

Schools likely to join trust after ESIF help

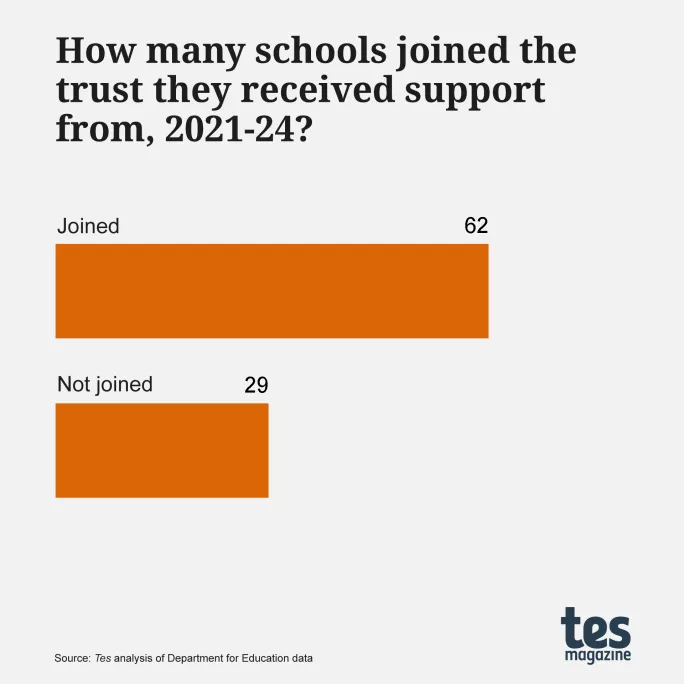

Our analysis also shows that 68 per cent of schools assisted under the scheme are now part of, or are set to join, the MAT they were supported by.

Of the 91 ESIF grants awarded between 2021 and 2024, 62 of the schools receiving support have now joined or are set to join the trust that received the improvement cash.

One such example is Ormiston Academies Trust, which has 42 schools. Ormiston supported Queensmill School in 2024-25, and advisory board minutes show that the school is set to join the MAT later this year.

ESIF “sometimes allows trusts to help schools get back on their feet”, said CEO Tom Rees.

In this case, it allowed the trust to provide operational support to the school, he added.

Trusts cannot support a school already in their MAT.

The 29 schools helped through ESIF since 2021 that did not join the trust supporting them either went on to join other trusts, have remained as single-academy trusts or were not academised.

Rob Tarn, CEO of the Northern Education Trust, which has 29 schools in the North East and North West, said that the ESIF grant seems to give trusts a leg up when it comes to expansion.

This, he said, makes sense, rather than passing over a MAT that has already worked with a school.

Emma Bradshaw, CEO of the Alternative Learning Trust, which has four alternative provision settings, said that for trusts that do not think the approach is fair, it is a case of “chicken and egg”.

“You’ve got to put yourself out there to get that [opportunity],” she said.

Lack of ‘fair funding’

As policymakers draw up plans for school improvement to sit with regional improvement teams, leaders say there are clear lessons to be learned from ESIF, including the need for sufficient funding.

Steve Rollett, deputy chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts (CST), said trusts are keen to support the wider sector, but that this “takes time and resources”.

In a recent CST survey, the majority of trusts said that they expect to spend from their reserves this year.

“In that context, funding support like ESIF is likely to be increasingly called on for the very intense support needed when a school needs urgent help,” Mr Rollett said.

Tes revealed earlier this year that there had been a jump in the number of MATs with reserves at levels suggestive of “financial vulnerability”.

Matthew Shanks, CEO of Education South West, agreed that financial pressures - caused by “a lack of fair funding for schools, as well as the impact of Covid-19” - could be behind the growing ESIF spend.

There was “no doubt” that schools need “greater financial support” and “the fact that increased funds for schools’ improvement were given support this”, he said.

Support needed earlier

But Mr Carratt questioned where resources for the school improvement teams would come from, and how the return on investment would be tracked.

Mr Carratt said the DfE will have to be careful not to “throw money under the auspices of improvement” that is not part of a long-term strategy.

He saw one of the benefits of the MAT sector as the offer of “long-term services and long-term vision for improvement”, which he said can take anywhere between three to five years.

The help should ideally be provided at an earlier stage “rather than through emergency intervention”, according to Mr Rollett.

Mark Blackman, director of education consultancy Leadership Together, agreed, saying a key lesson for the new teams is that “early conversations and swift action pays off in the long run”.

He added: “For schools that need support, there is always a need to act quickly; delays rarely mean that the issues solve themselves.”

There would be a continued need for trusts to step in due to the amount of “capacity” needed in school improvement, he said.

North East receives just one payout

The data also reveals a huge regional disparity in the amount of ESIF cash being handed out.

However, this does not appear to be down to the DfE rejecting applications, seeing as the vast majority of bids are accepted.

Between 2021 and 2025 to date, the North West received the most cash out of all nine regions. Since 2021, trusts in the region have received a combined total of £2,268,243 through 18 awards.

The region that has received the least funds in that period is the North East with just £120,570 handed out through just one award.

Between 2022 and 2025, small trusts - defined as those with fewer than 3,000 pupils - received the most grants, a total of 31.

Medium-sized trusts - those with between 3,000 and 7,500 pupils - received 30, and large trusts - those with more than 7,500 pupils - received 16.

Small- and medium-sized trusts received a similar amount on average, at £103,000 and £108,000, respectively, while large trusts tended to receive a larger wad, amounting to £123,518 on average.

Schools ‘tend to ignore advice’

Mr Tarn, whose trust received the only payment in the North East in 2023-24, said that the grant is “probably not a great use of public money”.

He raised concerns over the workability of support grants and the idea of regional school improvement teams, adding that “unless you have executive authority to tell people to do things, it doesn’t really work”.

“The problem with an advisory model is when people can take or leave your advice they will leave it a lot of the time,” Mr Tarn said.

The future of school improvement grants like ESIF is as yet unclear, but the DfE is yet to indicate that funds such as this will disappear with the introduction of regional improvement teams.

It is unclear as yet whether improvements suggested by the new regional teams will be compulsory.

A Department for Education spokesperson said the government is committed to high and rising standards in education, “investing in programmes and initiatives that drive long-term improvement, like the Emergency School Improvement Fund“.

“Since a period of lower demand during Covid 19, and with the expansion of eligibility requirements, we have seen an increase in schools who have accessed the ESIF.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article