More schools train mental health ‘triage’ staff amid ‘crisis’

More than a third of teachers report their school now has an emotional literacy support assistant (ELSA) as heads’ leaders warn schools “can’t afford to wait” for pupils to get support from backlogged health and social services, Tes can reveal.

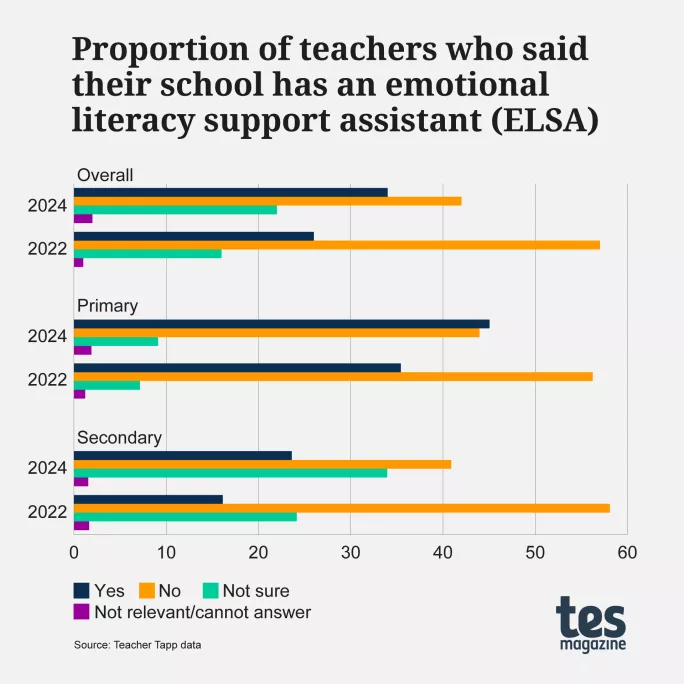

The proportion of teachers who said their school has an ELSA has jumped from around a quarter (26 per cent) to a third (34 per cent) in just two years, a poll carried out by Teacher Tapp and shared exclusively with Tes has shown.

Emotional literacy support staff are often teaching assistants (TAs) or other support staff who have undergone further training to be able to provide interventions for pupils struggling with mental health issues, such as anxiety or attachment issues.

They carry out one-to-one sessions with pupils outside of the classroom, addressing social and emotional development - usually meeting once a week for up to a term.

ELSAs ‘triage’ pupils but are not therapists

Leaders told Tes that they are increasingly using ELSAs as a form of early intervention to tackle pupils’ emotional wellbeing issues, which they say have increased after the Covid pandemic.

However, one leader warned that while ELSA interventions can act as a form of “front-line triage” for pupils who are struggling with their mental health, ELSAs are not therapists and should not be seen as replacing ongoing support from external mental health services.

ELSAs undergo a short period of training and then receive ongoing support from an educational psychologist.

Spiralling level of need a ‘mental health tsunami’

Heads leaders’ have previously described the spiralling level of need among pupils as a mental health “tsunami” threatening to swamp schools.

The growth in schools having such staff has been more pronounced in primary schools, according to the Teacher Tapp survey.

More than four in 10 (45 per cent) primary teachers said their school now has an ELSA - up from 35 per cent in 2022 - compared to less than a quarter of secondary teachers who said the same.

However, according to Teacher Tapp, secondary schools have also seen a rise from 16 per cent of senior teachers reporting their school had an ELSA to 23.6 per cent in two years.

- Report: Poor mental health ‘fuelling’ absence crisis, DfE told

- Children’s commissioner: Faster school mental health team rollout needed

- MPs: DfE should ensure support staff pay rises are funded

The survey reveals that teachers in schools with the highest proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals were more likely to report that their school has an ELSA.

Just over a third of teachers at schools with the highest levels of deprivation said ELSAs had been hired (33.8 per cent).

Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said there is “a crisis of mental health support in schools” despite increased government investment in its attendance mentor programme and the continued roll-out of mental health support teams.

Assistant general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, James Bowen, said the rise in ELSAs does not reflect more staff on the ground, but instead an upskilling of support staff such as teacher assistants due to a “growing need”.

‘Schools can’t afford to wait for external help’

“The long waiting lists and high thresholds to access services like the child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) are almost certainly playing a role, too, with schools knowing that they cannot afford to wait for external help to become available,” he added.

Emma Bradshaw, CEO of the four-school multi-academy trust, Alternative Learning Trust, with schools across London and South East, said that the huge rise in need was driving action from schools.

A report by the children’s commissioner in March revealed that nearly one million children and young people were referred to children and young people’s mental health services (CYPMHS) in 2022-23.

Meanwhile, a report published by the DfE in 2022 revealed there had been “inconsistent recovery of children and young people’s mental and physical health towards pre-pandemic levels”.

As a result, schools are having to battle increased challenges with “attachment issues” and “high levels of anxiety”, Mr Di’Iasio said.

Warren Carratt, CEO of Nexus Multi-Academy Trust - which has 15 schools across the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber - said the rise “reflects a shift in resourcing decisions”.

He said leaders are now seeking “to mitigate the impact on schools with the austerity-driven deconstruction of wider public services and the backlog in CAMHS”. Mr Carratt added that this has meant that schools have been forced to “fill the gap by prioritising this type of training or intervention”.

TAs have become ‘key workers’ since the pandemic

TAs - the members of staff most commonly given ELSA training - have become “key workers since Covid”, Mr Di’Iasio added, and are the “main points of contact for the most vulnerable students”.

Mr Di’Iasio said that the school he led before taking up the role of ASCL general secretary used its pupil premium, plus other funding, to upskill its TAs to ELSA roles. ELSA training can also be funded through inclusion funds, and some councils fund a certain number of places each year.

Julie Kelly, headteacher at West Meon Church of England Primary School in Hampshire, said her school has always had an ELSA. Currently, the early years assistant at the school is trained as an ELSA and is released to work with pupils.

However, she said that the school has recently increased its use of an ELSA from one to two afternoons a week, due to pupil demand.

Ms Kelly said that while interventions generally last for six weeks, some pupils now receive ongoing support. She added the rise in need has been sparked by a combination of the pandemic followed immediately by the cost-of-living crisis.

The pupils are “very aware of everything that’s happening”, Ms Kelly said, adding “that parents are now approaching the school asking for an ELSA intervention for their children” rather than the school making the initial suggestion.

However, Lisa O’Connor, vice president of the Association of Educational Psychologists and head of an ELSA programme in Leicestershire, warned that: “financial and time constraints” on ELSA staff within schools have meant that they can’t always respond to pupil needs and “have limited amount of ELSA time available to actually deliver interventions in some circumstances”.

Staff have ‘unseen roles’

Margaret Mulholland, ASCL’s SEND and inclusion specialist, said the increase in ELSAs had “more to do with the complexity of need being seen”.

Ms Mulholland said that the rise in ELSAs “reflects the often unseen roles and responsibilities being taken on by staff members”.

While Ms Mulholland said there was an increasing need before the pandemic, schools are now having to act due to a lack of specialist support.

Although leaders have said the availability of ELSAs is helpful, Jonny Uttley, CEO of 11-school trust The Education Alliance (TEAL), said that high levels of support staff attrition can cause difficulty in having to train new staff again to carry out the role.

Schools have faced increasing concerns over recruiting and retaining crucial support staff in recent years, as similarly- or better-paid roles with more flexibility are offered in other sectors.

However, Mr Uttley added that upskilling TAs as ELSAs can be a good form of professional development that could boost retention.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.