Is there any way back for Ofsted?

Jacky Kennedy is seething. An Ofsted report for a school in her trust has landed, and it’s the worst possible outcome: a downgrading from “good” to “inadequate”, with special measures required.

Like so many leaders across the system now, she has no faith in the judgement of the inspectorate. She not only feels Ofsted has failed to reflect the reality of her school, but that it has produced a report that is fundamentally flawed and unjust. The report, setting out how St Cuthbert’s Primary School is failing its pupils, draws from an inspection that was later dramatically revised. But the headline judgement remains.

Mater Christi Multi-Academy Trust, which runs the school in Windermere, Cumbria, tried to convince Ofsted that its findings were unfair, but the final report has now been published for all to see. The “ordeal” has left leaders feeling “helpless”, parents “in shock” and staff “deflated”, says Kennedy, the trust’s chief executive. “The repercussions have been enormous,” she says.

The inspection system has always attracted criticism from heads, especially from those at the sharp end of a disappointing judgement. But there is now a sense from more heads than ever, including those with “outstanding” judgements, that the process is unfair at best, and completely broken at worst.

Some supporters of Ofsted have tried to write this criticism off as a reaction to the death of headteacher Ruth Perry, whose family says she took her own life after a negative school inspection. But in truth, the tragedy has galvanised a battle-hardened profession to demand change on issues that have existed for some time, but that they have not felt able to speak publicly about previously.

Many commentators say Ofsted spotted this fact too late, and then reacted to it with piecemeal reform that failed to deal with the concerns and, in some ways, only made things worse.

So, the question needs to be asked: does Sir Martyn Oliver - poised to succeed Amanda Spielman as the watchdog’s chief inspector - have anything left to work with at Ofsted, or does the whole thing need to be scrapped and the inspection system built again from scratch?

At present, the majority of headteachers and multi-academy trust (MAT) leaders are not arguing for Ofsted to be abolished altogether. Instead, they want certain areas of the current system radically improved.

The most common area cited for improvement is consistency of inspections, which one government official, speaking anonymously, describes as “the big challenge” facing Spielman’s successor.

The experience of St Cuthbert’s illustrates what this inconsistency feels like at ground level. The rural primary teaches 41 pupils - many of whom speak English as an additional language and whose parents work in the local hospitality industry.

It received “the call” in February of this year - a month after appointing a new head, and 18 months after becoming an academy and joining Mater Christi MAT.

Two days of inspection - ungraded, then graded - resulted in a draft report that downgraded the school to “requires improvement” in two areas and “inadequate” in three areas, with an “ineffective” rating for safeguarding.

After the trust flagged “inaccuracies” in the draft findings, a third visit was carried out to collect what Ofsted described as “additional evidence”.

By this point, the rural school had hosted five inspectors across three separate visits, in the space of three months. The inspectorate showed “no regard for the stress and anxiety this places on a school”, says Kennedy.

Nonetheless, leaders were relieved when both of the areas that were re-inspected were upgraded to “good”, and the safeguarding judgement was overturned.

Far from “ineffective”, the final report states that staff are “well trained” in safeguarding and “report concerns promptly”, while leaders “take appropriate action” and “are aware of the safeguarding risks within the local area”.

This did not end the school’s woes - more on this later - but how was it possible for two inspection teams to come to such opposing conclusions?

Kennedy is adamant that the school’s safeguarding approach, for example, was left completely untouched in the interim period.

“There wasn’t anything to do…there was nothing wrong with the safeguarding in the first place,” she says.

Similar issues are happening across the system, according to heads, and sector leaders say they are now living in fear that their schools - and careers - can be turned upside down on the basis of one erratic judgement.

“You daren’t say anything wrong to an inexperienced inspector, because then they say: ‘You’re “requires improvement”’”

The growth of MATs is driving this recognition of inconsistency. Whereas, in the past, headteachers went through an inspection “in isolation”, without knowing exactly how their school compared with others, working at a MAT broadens that outlook, says Nick Osborne, CEO of Maritime Academy Trust in Kent.

“When you lead a MAT, and you see the same standards in different schools or the same curriculum in different schools, and you see them treated differently by different inspectors, it really highlights the inconsistencies in the process - it’s not the science it’s painted out to be,” he argues.

Finding this out the hard way has left him a “nervous wreck” when it comes to Ofsted, he says.

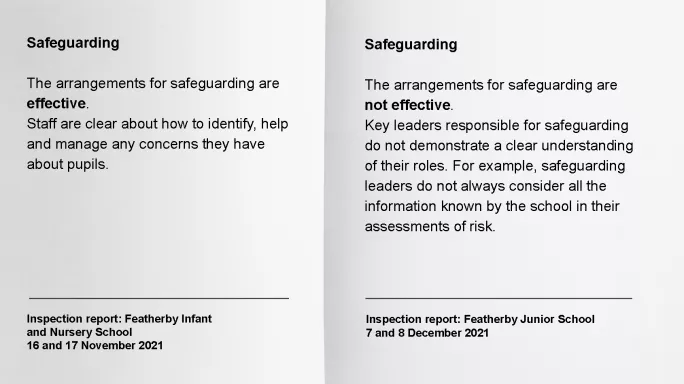

Two of his schools, a junior and infant school based on the same site, with the same safeguarding team and “the same policies, procedures and record-keeping systems”, were inspected three weeks apart - by different teams, and with very different results.

Safeguarding at Featherby Infants School, in Gillingham, was deemed to be “robust” and the school was a “good” overall. Over at the juniors, a different inspection team found safeguarding to be “ineffective”, leading to an “inadequate” headline grade.

At the infants, leaders were “resolute in their approach to providing a safe environment for all”, the report states. But at the juniors, inspectors found: “Key leaders responsible for safeguarding do not demonstrate a clear understanding of their roles.”

“It was absolutely ridiculous,” says Osborne, who insists the infants and juniors are only separate entities for funding purposes. “They’re one school - it’s only a technicality, the difference between these two schools,” he adds.

Six months later, the juniors received a glowing follow-up report and a “good” rating across the board.

Osborne, however, remains “scarred” by his earlier experience, which he holds up as an example of the unpredictable and subjective nature of the system.

As part of the package of measures introduced in response to the Ruth Perry case, inspectors will now return more quickly to schools that have been graded “inadequate” overall owing to ineffective safeguarding, where all other judgements were “good” or better.

While this might dampen the impact of a single snapshot finding on safeguarding, it does nothing to alleviate inconsistency more generally, or the anxiety it causes.

So, what exactly is causing these inconsistencies?

For Adrian Rogers, who has been chief executive of the 15-school Chiltern Learning Trust for the past eight years, it comes down to “absolutely shocking…disgraceful” variations in the quality of inspectors.

Ten of his trust’s 15 schools have hosted Ofsted inspectors in the past 11 months. While some inspectors have, in his eyes, been “excellent”, he describes several as “poor”, particularly in their “interactions with the senior staff in the schools and with the children [and] their knee-jerk reaction to very flimsy evidence bases”.

“They’re not able to synthesise the information with competent and good judgement,” he expands.

Leaders who lack confidence in inspection teams are then less willing to impart information, making the whole process less meaningful, he suggests.

“You daren’t say anything wrong to an inexperienced inspector, because then they say: ‘Well, that’s it, you’re “requires improvement”’,” he says. “They haven’t got the ability to unpick what’s important and what’s not.”

Rogers is far from alone in feeling that too many inspectors are simply not up to scratch. Lee Mason-Ellis, CEO of The Pioneer Academy, says some even misinterpret Ofsted’s framework - not realising, for example, that if the quality of education is not judged as “good”, it does not necessarily follow that leadership cannot be classed as “good”.

“This can completely undermine the progress made at vulnerable schools, which have previously been entrenched in systemic failure,” he says, calling for further training in this area.

Mason-Ellis, whose trust runs 15 primaries across Kent and south London, also highlights the varying levels of experience of inspectors, some of whom “have never taught or been in a leadership position at a primary or secondary school”, he says.

Even those with years of leadership experience may only have worked in one region, or in one type of school, sometimes leading to extreme misperceptions.

For example, Osborne recalls how one inspector warned that his primary pupils’ enthusiasm about selling poppies could be a sign of “white supremacy”, given the school’s position in a predominantly white British part of coastal Kent.

Rogers, whose trust operates in areas such as Luton with large Muslim populations, has been questioned by Ofsted about the credentials of his “overseas-trained” staff; he employs none.

“This assumption doesn’t happen in our rural schools,” he points out.

It would be difficult to remove inconsistency from the system altogether; inspections carried out by humans will always be somewhat subjective. There is even research by FFT Education Datalab showing that similar schools receive different grades based on “arbitrary” factors, such as the gender of the lead inspector - men are more generous in their grading of primary schools, for example.

But there are also concerns that the quality of inspectors has declined over time. Rogers has overseen 52 inspections over the course of his career, “and the quality of the last 10 has been markedly different to the first 40”, he says.

If there has been a decline in quality, one factor could be inspector turnover, which rose to 14 per cent last year, according to Ofsted’s most recent annual report. This followed pre-pandemic warnings that inspectors were quitting to take up better-paid jobs in MATs.

Prioritising the recruitment and training of inspectors, it seems, could go some way towards addressing Ofsted’s problems.

But there is another potential reason for variable inspections: Ofsted’s 2019 framework. The framework emphasises the school curriculum, while reducing the focus on exam results, and some feel its more nuanced approach can encourage “arbitrary” judgements.

While many heads retain grim memories of the data-heavy inspections of old, and welcome Ofsted’s shift in focus, there is also a widespread feeling - including within the Department for Education - that the pendulum may have swung too far.

Instead of scrambling to present inspectors with performance data, schools instead feel compelled to “create loads of curriculum documentation…and over-intellectualise it”, says one government official who wished to stay anonymous. A judgement could rest on how well a school talks a good game on curriculum, critics say, rather than what they actually do.

Meanwhile, many inspectors, according to school leaders, do not have the skills, training or phase/subject knowledge base to judge curriculum fairly or accurately across different schools: there is a mismatch between the aims of the framework and the capacity of Ofsted to meet those objectives.

The new framework, the official says, clearly places too much weight on curriculum, as opposed to what students “can do at the end”.

This was a concern expressed earlier in the framework’s life by two prominent MAT chiefs: Sir Martyn Oliver of Outwood Grange Trust - who is about to take the reins at Ofsted - and Sir Dan Moynihan, chief executive of the Harris Federation.

At the time, Sir Dan called it a “middle-class framework for middle-class kids”.

Does he still hold these concerns?

There is more of a focus on outcomes now but it could still be stronger, he says. “Nobody gets the job saying: ‘I studied X, Y and Z’ - it’s the qualifications they’ve got.”

He continues: “So it’s finding that balance between curriculum and outcomes. And certainly, in the early stages of this framework, outcomes weren’t talked about enough. They are talked about more now, but I personally would like to see a greater emphasis on that.”

“The problem with the framework is it could work reasonably well in a secondary, and for a small primary, it’s just a complete contortion”

Former chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw agrees, calling the new framework “a gift to the education charlatans in the system who talk a good game on the curriculum…but [whose] results are awful”.

And it is unfair on high-performing schools in disadvantaged areas that perform well on progress measures, Sir Michael feels. “It upsets headteachers who work hard to show, actually, their kids are doing well,” he says.

Research by FFT Education Datalab suggests there is still a link between progress scores and Ofsted ratings, but there are some noticeable outliers.

Sir Michael also worries that the new framework leads to fewer questions being asked about efforts to boost the performance of students from poorer backgrounds. “I think that is absolutely outrageous…morally unjustifiable,” he states.

Sir Michael’s concern is, to some extent, borne out in inspection reports. For example, an analysis of Ofsted inspection reports carried out by School Dash earlier this year for Tes found that mentions of “disadvantage” in Ofsted reports were at their lowest levels since 2014, while inclusions of the phrase “pupil premium” had fallen by around 40 per cent.

Another common concern about the framework is the pressure it places on classroom teachers and department heads tasked with answering complex questions about curriculum intent and sequencing - a particular challenge in primaries lacking expertise across all subjects.

There is always the fear that Ofsted will home in on a part of the curriculum that a school has not looked at for a while, says Catherine Lester, an executive principal at LEO Academy Trust, which runs eight primaries. “In a primary, you can’t improve everything all at once. It’s just not manageable,” she says.

It may come as little surprise, then, that the smallest primary schools are five times more likely to be rated “inadequate” by Ofsted than the largest ones.

While the watchdog claims to “always take each school’s circumstances into account on inspection, including the very smallest”, that does not always appear to happen in practice, leading to widespread complaints that the framework tries to judge primaries through a secondary lens.

Such critics include Jonny Uttley, CEO of Education Alliance Trust, which runs eight academies - a mix of secondaries and primaries - in Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire. “I think the problem with the framework is it could work reasonably well in a secondary school, it’s less appropriate in a primary school, and for a small primary school, it’s just a complete contortion,” he says.

But while the framework might be flawed, another charge being made against Ofsted from the profession, in the wake of Ruth Perry, is that it places intolerable pressure on leaders by refusing to recognise they are already under an enormous amount of strain.

Years of austerity and a global pandemic have left public services creaking, forcing schools to step into roles that would once have been the domain of social services and the NHS. But Ofsted is seen as having failed to sufficiently alter its expectations in line with these extra challenges.

Take Covid, for example. As the Omicron variant took hold, and as heads warned that schools were in “crisis mode” owing to juggling in-person lessons and online teaching, all while facing severe staff shortages, Ofsted refused calls to extend a pause in routine inspection.

Although schools were theoretically able to request inspection deferrals if they were hit by disruption caused by Covid, around a third of such requests were rejected during the 2021 autumn term.

Former inspector Adrian Lyons sees Ofsted’s conduct during the pandemic as a tipping point for the current crisis of confidence.

Before leaving Ofsted in 2021, he “heard heartbreaking stories of school leaders and staff recounting how they supported families during lockdown”. But “any mentions in draft reports were struck out”.

Ofsted’s “refusal to celebrate what dominated school activity and continues to have a significant impact” is “a slap in the face to the teaching profession and to school leaders in particular”, and “surely the real reason for the systemic lack of confidence in Ofsted”, he says.

And there is little sense that the regime takes into account the continued fallout of the Covid crisis - a point Lester picks up. “Having been through a huge pandemic, to just go straight back into this fairly difficult framework and say: ‘OK, everyone’s back on track now, let’s crack on.’ It’s been difficult and stressful,” she says.

Ofsted was accused of a similar rigidity in its insistence on inspecting schools during last summer’s record-breaking heatwave as temperatures climbed to 40 degrees, red weather warnings were issued and pupils were being told to stay home.

Inspection now feels to many as something that exists outside of the reality of schools.

Despite this groundswell of discontent, Ofsted has appeared unwilling to listen to its critics. While it has recently announced changes to its complaints processes, this has followed years of warnings that the system is stacked against schools. A Tes investigation back in 2017 had shown how it was “virtually impossible” to overturn an Ofsted verdict - but significant plans for reform were only announced in June of this year.

“Their reluctance over the years to reform the complaint system - it’s been like banging your head against a brick wall,” says Sir Dan. “It’s good that they’re now consulting on making a much more responsive complaint system. It’s just a shame it’s taken so long for that to happen.”

St Cuthbert’s, for example, is stuck with its “inadequate” judgement - even though this grade is based on an inspection that Ofsted itself felt was lacking in evidence.

While draft findings were overturned in all of the three areas checked by a separate inspection team, Ofsted would not re-inspect the remaining three areas - claiming that the evidence was already “banked”, according to Kennedy.

In the inspectorate’s lingo, the original inspection was “incomplete”. But Kennedy is baffled as to why the original report has not been thrown out completely. “At what point is an inspection flawed,” she asks.

“They were more fixated on their process than on how this was impacting on the head,” Kennedy says.

Is this sluggish response to criticism and unwillingness to listen a sign of an organisation mimicking its leader? There are many who argue this is the case.

While often hugely complimentary about Spielman’s focus and intellect, there is a widespread feeling in both the DfE and among sector leaders that she has got the tone and communications policy of Ofsted wrong.

Some say she takes criticism incredibly personally, takes defensive positions and has not listened to advice about softening the tone of the organisation.

“Ofsted is a job that forces you into a bunker mentality where you think everyone’s out to get you all of the time - because a lot of the time, people are out to get you”, says the anonymous government official, giving their personal view. “I think Amanda has too many times ruled out criticism as being just ‘those lot trying to destroy Ofsted again’ - when, actually, it was the right criticism,” they add.

There are many examples of Spielman appearing tone deaf, including in the admission to the BBC that she had not reached out to Ruth Perry’s family, and her claim that the vast majority of schools find inspection a “positive and affirming experience”.

Many stress, though, that she has done much good, too. The organisation is more evidence-informed, more robust and better run than it has been, supporters claim.

There is also a view that Ofsted is merely an outlet for the pent-up frustration of an angry profession.

“If you look back at how Ofsted was before [Spielman] started and remember how we felt about it and what we were saying then, actually, if we’re really objective, Ofsted is in a better place now,” says the anonymous official. “It’s just that it’s not perfect, and [Ofsted] is bearing the brunt of a lot of frustration with a lot of other things.”

But for others, Spielman’s public response to critique and inability to adapt has undermined her strengths, as has her inability to communicate effectively. And this has exacerbated the wider problems with the organisation.

The main way in which all of these frustrations have surfaced is in the debate over single-word judgements, widely seen as the fundamental problem with the current inspection system.

While headline grades have always been controversial, they have never carried more weight than now, partly due to the increased threat of a school being rebrokered or forced into a MAT. New government powers are being introduced allowing intervention in schools that get two consecutive Ofsted reports rated less than “good”, despite warnings this will create a “sword of Damocles” for heads.

Meanwhile, population changes are leading to falling pupil rolls in many schools, which, as Osborne points out, can make an “inadequate” rating “catastrophic”. “If you lose pupil numbers with the funding issues at the moment, you are in massive trouble. And then it’s a spiral,” he says.

At the same time as having heavier implications than ever, the grades have never been seen as less reliable, for all the reasons outlined in this article. Even Sir Michael has changed his mind about them.

There is also a strong concern that the current regime is exacerbating the teacher and leader recruitment crisis.

“I don’t want to be part of a system that judges like that”

“The single-word judgement, if it was ever appropriate, it’s just so completely not so now,” says Uttley. “The consequences for schools and trusts of a negative inspection are so huge…there’s this cusp between ‘good’ and ‘requires improvement’, which is basically the difference between, you’re fine, and you’re in a world of trouble.”

“And what that then brings with it in terms of leadership anxiety, I think you can trace a kind of direct line from that straight through to why people don’t want to teach,” he adds.

Despite the strength of feeling on this, Spielman has simply said that single-word judgements are “not wrong” and that parents “value the simplicity and clarity” of them.

It is unclear on what evidence the latter line of argument is based, as less than a third of UK adults are confident that Ofsted ratings provide an accurate assessment of how good a school is, according to a recent YouGov poll.

Separate research has found that an Ofsted inspection outcome can be years out of date by the time a child is attending that school and is “not particularly useful” for parents.

“The one-word judgement was of its time, and for me, the system, school leadership, has moved beyond it, and Ofsted needs to catch up,” says Uttley. “Until that’s changed, then everything else is tinkering around the edges.”

So, is the inspectorate as we know it still viable, or is the Ofsted brand now too damaged even for a substantive rebuild to work?

On the whole, heads say many of its problems appear to be fixable with the right priority list, willingness to change and sufficient resources. Most importantly, they say, Ofsted must listen to the profession, not least to avoid exacerbating the current exodus of teachers and leaders.

“I think they have to realise the dam has broken and people are really deeply unhappy,” says Lester. “I don’t think anybody is saying that we shouldn’t be held to account - we should be, most definitely, but not to the detriment of the good work that schools do.”

Similarly, Sir Dan wants to see a strong Ofsted, but one that reduces the “fear factor” for schools. The fact that Ofsted is a key factor in teachers’ decisions to leave the profession is “a bit of a crisis”, he says.

But there is a fine balance to be struck, he suggests. “We need somehow for Ofsted to keep its function of having rigour, and highlighting good and bad practice, but at the same time downscaling the high stakes nature of those visits.”

Time to save the inspectorate is running out: the new HMCI, due to start next January, will likely have less than 12 months before a general election takes place.

Labour has already put forward a radically different vision of Ofsted, and plans to consult on replacing inspection grades with a school scorecard and introduce an annual school safeguarding check.

The plans have been generally well received, though school standards minister Nick Gibb said they amounted to a decision to “go soft on education standards”.

Sir Dan thinks scorecards are worth exploring, but also sounds a note of caution: “The examples that exist, say in parts of America, they’ve become increasingly complicated over time, as more and more criteria have been added to them.

“So whether a balanced scorecard is better or not depends on what’s in it. And we need some work on that, and some public discussion, and I’m sure that’s what will follow.”

But for some, the damage is already done. Following a “brutal, gruelling, patronising” inspection, one headteacher, who runs a pupil referral unit (PRU) and who wants to remain anonymous, is now thinking of leaving education altogether after 20 years.

Among the head’s many grievances is the fact that the framework called for a “calm” atmosphere in order to obtain a “good” rating. “How can you judge a PRU on that,” the head asks.

“I have thought of nothing else since that inspection other than never putting myself through that again,” they say.

Ultimately, the inspection outcome was positive. But, the head concludes: “I don’t want to be part of a system that judges like that.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article