Less than 2 in 5 ‘good and improving’ schools get top Ofsted rating

Less than two in five improving schools told they had a chance of an “outstanding” grade at their next inspection were actually given Ofsted’s top rating, Tes analysis reveals.

Heads’ leaders have said the figures are evidence of the “morale-sapping” and “disheartening” impact of the inspection system, which they claim “does very little to support school improvement”. The figures have also led to renewed calls for a shake-up of the four-grade system.

Tes’ investigation shows how a change of Ofsted rules, the introduction of a new framework and the Covid pandemic have led to long waits and disappointment for many schools hoping to secure an “outstanding” grade.

Before 2018, Ofsted could convert ungraded inspections of “good” schools to full inspections if it believed the school could be judged as “outstanding”.

However, from 2018 it changed its approach, telling “good and improving” schools at ungraded inspections that they would instead get a full graded inspection within one to two years.

Schools struggling to get Ofsted top grade

Tes revealed last month that the number of “good” schools receiving the top grade from Ofsted has fallen dramatically under the new approach.

Now a Tes investigation reveals the fate of those “good” schools that were told by Ofsted they had shown signs of improving further.

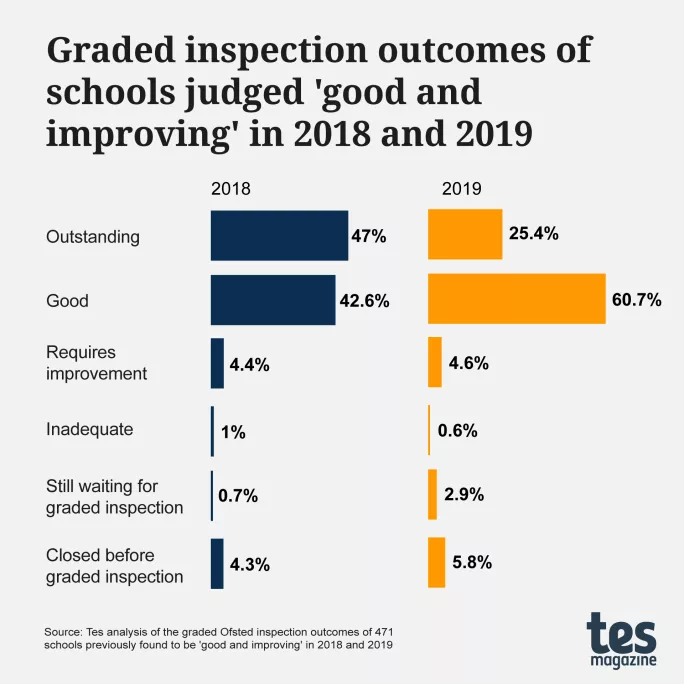

The investigation has identified the schools that were told they were “good and improving” in the two years after Ofsted’s change came into effect (2018 and 2019), and analysed which grades they were awarded when they eventually received their full inspection.

Just 39 per cent of schools found by the watchdog to be “good and improving” in ungraded inspections in 2018 and 2019 were upgraded to “outstanding” at a subsequent graded inspection.

Of the 471 schools included in the Tes analysis, just under half (49 per cent) remained “good” when they received a full graded inspection.

And, despite receiving a full inspection because they were seen to be on an upward trajectory, 25 schools were downgraded from “good”: 21 to “requires improvement” and four to “inadequate”.

There were also 23 schools that closed to become academies before receiving a graded inspection, and seven schools were still waiting for a graded check.

Tes also compared outcomes by phase, and found that in both 2018 and 2019 “good and improving” secondaries were more likely to go on to be upgraded to “outstanding” than primaries.

Some 44.4 per cent of primaries judged “good and improving” in 2018 went on to be upgraded, compared with 65.6 per cent of secondaries.

In 2019 the corresponding figures were 23.4 per cent of primaries and 38.4 per cent of secondaries. However, in 2019 only 13 secondary schools were found to be “good and improving”, compared with 145 primary schools.

Upgrades halved under new framework

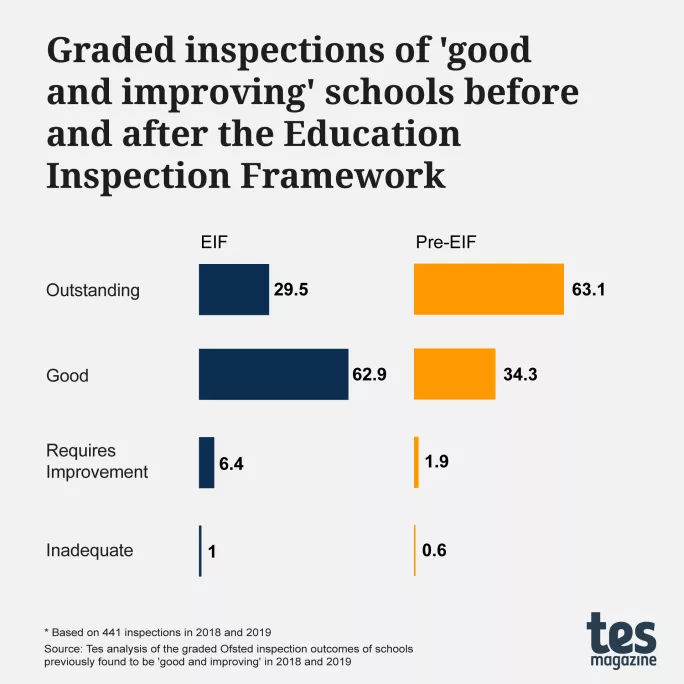

The analysis also reveals that “good and improving” schools were more than twice as likely to get Ofsted’s top grade before the watchdog’s Education Inspection Framework was introduced in September 2019.

Some 29.5 per cent of schools identified as “good and improving” in the 2018 and 2019 calendar years and graded under the Education Inspection Framework (EIF) went up to “outstanding”.

The proportion was far higher - 63.1 per cent - for “good and outstanding” schools graded before September 2019 under the previous framework.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said that the findings are more evidence of the “morale-sapping” impact of an inspection system in which the “goalposts have shifted, making ‘outstanding’ judgements harder to obtain”.

He added that the “possibility of actually dropping a grade may make the prospect of a graded inspection in a ‘good and improving’ school something to dread rather than welcome”.

Section 8 Ofsted inspections involve ungraded visits by inspectors, whereas Section 5 inspections provide a judgement that results in an “outstanding”, “good”, “requires improvement” or “inadequate” grade.

An Ofsted spokesperson said: “Our expectations for children’s education are higher now than they were 10 or 15 years ago, and the way we inspect schools has also evolved. We set a higher bar for schools to achieve the ‘outstanding’ grade under the introduction of the Education Inspection Framework in 2019.

“The ‘outstanding’ judgement needs to be challenging and exacting, as it demonstrates that schools are consistently and securely doing everything that makes a school good, and going beyond that to deliver the best possible education.”

Ofsted follow-up inspections: ‘It’s demoralising’

One head at a London school that was downgraded to “requires improvement” after being forced to wait more than three years for a follow-up Section 5 inspection, and who wishes to remain anonymous, told Tes that the inspector carrying out the graded inspection told them “to take no notice of your previous inspection because I’m not taking any notice”.

The leader added that schools that were judged to be “good and improving” under the former framework should not be penalised for being made to wait and then be measured under an entirely new system.

The school was judged under two separate frameworks because its Section 8 inspection occurred before the Education Inspection Framework was introduced in September 2019.

“It’s demoralising. We stick to rules, we stick to timetables, we stick to fairness and everything, but we’re not being treated fairly,” they told Tes.

- Ofsted: “Outstanding” grade “out of reach” for “good” schools

- Inspections: More schools keep “outstanding” grade

- School ratings: “Most” Ofsted grades align with exam result

James Bowen, assistant general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, said the Tes analysis will “reinforce the view of many school leaders that Ofsted inspections do very little to support school improvement” .

“Not only that, but there is a strong sense that they are failing to consistently offer a fair and reliable judgement on the effectiveness of their schools and improvements they have made,” he added.

Mr Bowen said the findings further highlight the “pressing need for a fundamental review of the inspection system” to deal with the “damaging impact” on staff wellbeing and ensure that reports paint a more accurate picture of schools.

“That must mean an end to blunt single-grade ratings. School leaders accept the need for accountability but there has to be a more humane and intelligent approach than the blunt system we have currently,” he added.

Schools still waiting for recognition

Although Ofsted had planned to return to “good and improving” schools within two years, the onset of the Covid pandemic has resulted in much longer waits.

More than three-quarters of the schools (77 per cent) that got a Section 8 in 2019 have waited three or more years to receive a follow-up Section 5 inspection after Covid.

In total, across the “good and improving” schools from 2018 and 2019, 39.4 per cent (186 schools) have waited three or more years for their graded inspection.

This includes seven schools that are still waiting for an inspection.

Ofsted paused routine inspections from March 2020 and did not resume them until the start of the 2021-22 academic year.

Where Covid has meant that the gap between an ungraded inspection and the subsequent graded inspection was longer than intended, the likelihood that the picture in that school will have changed will potentially increase.

Tom Middlehurst, inclusion specialist at ASCL, said it was “very difficult” for Ofsted to achieve its planned time frames immediately after the pandemic, but added that it would be “disheartening” for schools told that they were on an upward trajectory to “now be told, actually, they’re not” .

“It comes down to the single-phrase judgements, and when we look at those reports, those schools, they do identify areas of strengths and areas of improvement,” he said.

“But as far as parents are concerned, they won’t. They won’t see that reflected in the overall effect of this judgement. So it all comes back to that single-phrase judgement ultimately.”

Call for review of grading system

Steve Rollett, deputy chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts, said: “With the overwhelming majority of schools being judged ‘good’ and it being harder to be judged ‘outstanding’ under the framework introduced in 2019, it would be reasonable to ask whether there might be a better approach than the current four-point grading system.

“This is one reason why we’ve been calling for it to be reviewed.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article