‘Outstanding’ grade ‘out of reach’ for ‘good’ schools

The shrinking chance of schools moving from “good” to “outstanding” is revealed in a Tes analysis that shows how Ofsted’s four-grade system is redundant, according to school leaders.

The trend coincides with changes made by the schools inspectorate that are widely seen as having raised the bar for “outstanding” grades.

Experts say that this, combined with a lower threshold for government intervention in schools, means that heads now face a “binary” Ofsted system where a “good” rating is the best they can hope for - but also the minimum required.

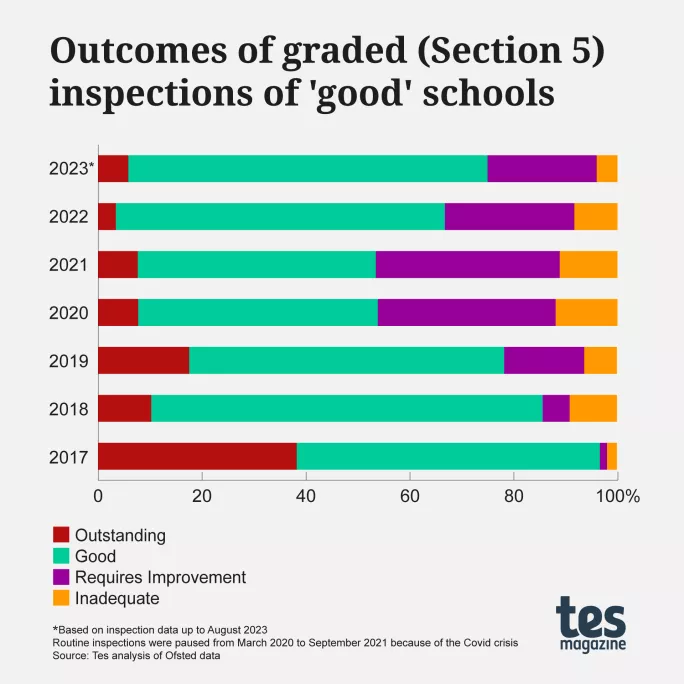

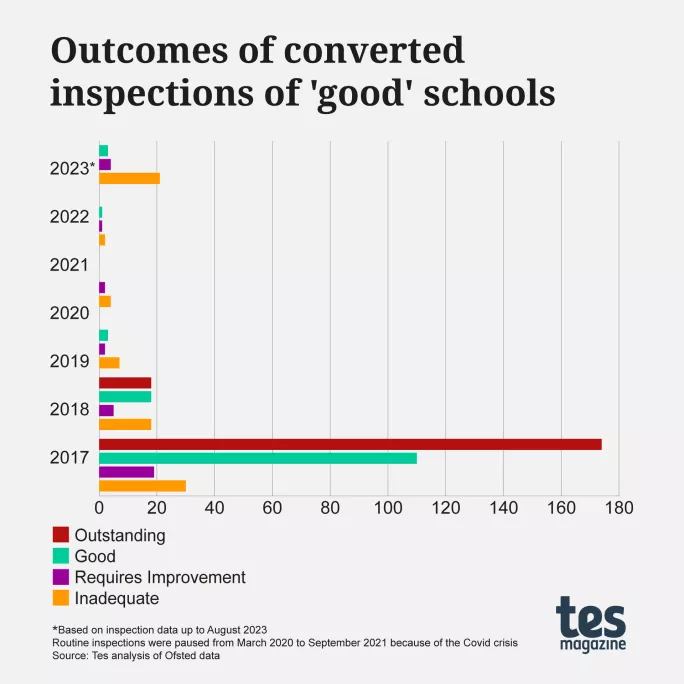

Our analysis shows how changes made under Ofsted’s current leadership have: dramatically reduced the proportion of “good” schools rated as “outstanding” after a graded inspection - from four in 10 in 2017 to less than one in 20 last year; and cut the number of “good” schools being upgraded after converted inspections from 174 to zero.

At the same time, more than 4,000 “good” schools have gone without a graded inspection for at least a decade, the findings show.

Tom Middlehurst, inspection specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said the analysis reinforces ASCL’s impression that “the goalposts have shifted, making it much more difficult for schools and colleges to obtain an ‘outstanding’ grade during an inspection”.

Ofsted operates a four-grade inspection judgment system for schools: “outstanding”, “good”, “requires improvement” and “inadequate”.

- Ofsted: More than four in five top-rated schools downgraded

- Inspection: “Outstanding” schools exemption is lifted

- Background: Ofsted accused of moving goalposts on “outstanding” schools

There have been calls for single-word inspection judgements to be scrapped, with Labour promising to consult on this if elected.

However, heads’ leaders warn that, in reality, the four-grade system is already less relevant due to the difficulty of securing a top rating.

In 2017 around four in 10 “good” schools facing a graded inspection saw their rating improve to “outstanding”, but this fell to less than one in 20 last year.

This appears to have happened partly as a result of changes to ungraded inspections.

Top Ofsted grade more difficult to achieve

In January 2018 Ofsted introduced a policy whereby inspectors could convert an ungraded Section 8 inspection into a graded Section 5 inspection only if they had concerns, not if they saw improvements.

For “good” schools showing improvements, inspectors could instead schedule a full graded inspection for between one and two years’ time.

In 2017, before the change took effect, there were 174 schools that moved from “good” to “outstanding” following converted inspections. This amounted to more than half of all converted inspections of “good” schools that year.

The following year 18 “good” schools were upgraded following converted inspections. But since then there have been none.

The Covid pandemic, which resulted in routine inspections being paused from March 2020 until September 2021, disrupted Ofsted’s plan to revisit all improving “good” schools within two years.

An Ofsted spokesperson said Covid “not did not stop us from carrying out these types of inspections, but it might have sometimes meant that it took us longer than it otherwise would have”.

Schools less likely to be upgraded

Tes also looked at the outcomes of all full graded inspections of previously “good”-rated schools since 2017.

This shows that 38 per cent of graded inspections of previously “good”-rated schools in 2017 resulted in upgrades. This fell to 10.2 per cent in 2018, and was 17.3 per cent in 2019.

Since then the figure has stayed below 10 per cent, with 3.4 per cent of schools upgraded from “good” in graded inspections in 2022, and 5.7 per cent in 2023, based on figures up to the end of August.

Experts say the decline in “outstanding” judgements has been driven by design, due to a premise that, by the end of the last decade, there were simply too many top-rated schools due to the fact they were exempt from routine inspections until 2021.

The exemption resulted in the proportion of schools with the top rating rising to around one in five.

Two years ago Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman said that halving the number of “outstanding” schools would be “realistic”. And last year Ofsted produced a report revealing that 83 per cent of previously top-rated schools had been downgraded.

At the time Steve Rollett, deputy chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts, warned that the goalposts for “outstanding” ratings had changed under Ofsted’s 2019 Education Inspection Framework.

Under previous inspection frameworks, he said, schools did not have to meet every single grade criteria in order to achieve an “outstanding” grade. But he said this changed under the new framework.

Siobhan Meredith, executive director of education for the Ted Wragg Multi-academy Trust, has led a primary school to “outstanding” twice, under two different frameworks.

She is clear that it is “absolutely” more challenging to do so now under the current framework due to the focus on curriculum sequencing.

“If you are a primary school teacher, you are teaching a huge range of subjects across the week and every single one of those subjects needs to be really well sequenced, with a clear intent, excellent implementation and then a really great impact for children,” she said.

“And equally, it is not just about the teacher. You have to be able to show that children are able to have had that learning and knowledge embedded in their long-term memory, be able to recall previous lessons and link to previous learning. This is more challenging.”

Our analysis also shows that “good” schools are going without a graded inspection for up to 14 years, with 4,135 schools waiting 10 years or more.

Of these, 2,777 have had two successive ungraded inspections.

Ofsted ‘now a binary system’

Another significant change to school inspections has come from a new government power to intervene and issue academy orders to what it classes as “coasting schools” that receive two less-than-“good” ratings in a row.

This means that, with “outstanding” grades out of the reach for an increasing number of schools, the vast majority of heads now either obtain a “good” rating or one deemed to signify underperformance.

Mr Middlehurst said: “If it is now very difficult to obtain an ‘outstanding’ rating - as appears to be the case - this, in turn, means that for most schools and colleges the system is actually a binary one between either ‘good’ or a negative rating, rather than the four-point system that it appears to be on the surface.”

He said the framework had been changed “in such a way that what was once judged to be one grade is no longer deemed to merit the same grade”, which was ”a fundamental weakness of the inspection system”.

A former Ofsted His Majesty’s inspector (HMI), who spoke to Tes anonymously, suggested that the changes meant that highly performing schools no longer fixed their sights on a top rating.

They said: “The schools I work with include some very highly effective schools who would have most likely been viewed as ‘outstanding’ under previous frameworks but are now not focused on achieving this rating because it is seen as being more out of reach.

“Their focus is only ensuring they are a ‘good’ school.”

Approached by Tes, an Ofsted spokesperson said: “We set a higher bar for schools to achieve the ‘outstanding’ grade under the introduction of the Education Inspection Framework in 2019.

“The ‘outstanding’ judgement needs to be challenging and exacting, as it demonstrates that schools are consistently and securely doing everything that makes a school good, and going beyond that to deliver the best possible education.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article