Attendance: what’s gone wrong and how can we fix it?

Speaking to MPs investigating persistent absence in March, Dame Rachel de Souza described school attendance as one of the “issues of our age”.

There are plenty of people within schools and in government who agree with the children’s commissioner.

Policymakers have been beating the drum on the importance of attendance since the reopening of schools in 2021. Ex-schools minister Robin Walker recently told Tes that data on attendance was “a priority” during his time at the Department for Education. Meanwhile, former education secretary Kit Malthouse said raising attendance rates was one of his “key missions”, and Nadhim Zahawi, another former education secretary, told parents that their children turning up at school was “simply non-negotiable” after the launch of his White Paper last year.

- Background: New attendance dashboard launches to “tackle absence”

- Covid: One-third of 12- to 15-year-olds still unvaccinated

- Pandemic: Covid inquiry will look at the impact of school closures

Most school leaders would agree that strong attendance is vital. One trust leader described persistent absence - pupils missing one in 10 sessions or more - as a “battle”. And there can be no doubt that schools are going to huge lengths to improve the situation, including collecting children from home, coaxing them in with creative timetabling and providing financial support to parents.

But the elephant in the room for many is that, while schools are doing their best to tackle the symptoms of absence, many feel the systemic causes of low attendance stretch beyond the limits of their control.

Attendance advisers, alliances and mentors are some of the DfE’s efforts to help schools tackle the problem, but some have questioned whether, with all the good faith in the world, these can fix an issue that may be as much about parental poverty and anxiety as getting pupils into the classroom.

How bad is school attendance?

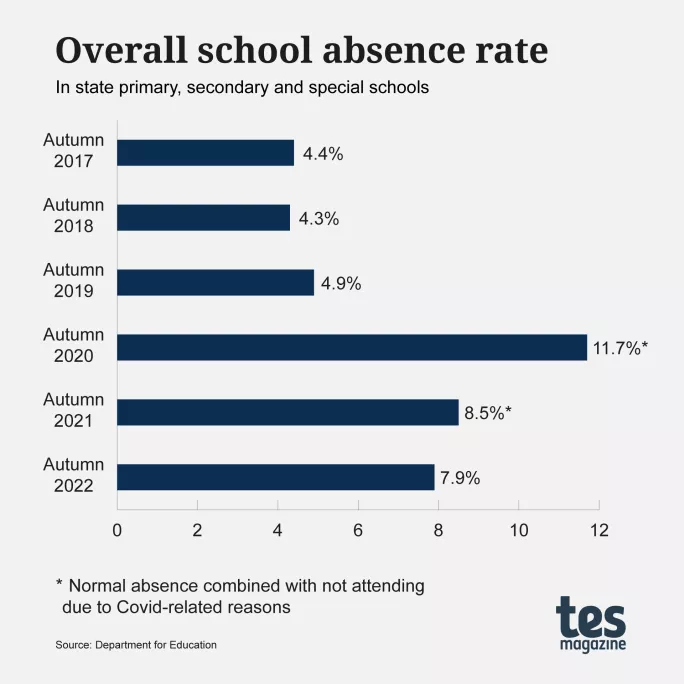

Data for the autumn term of this academic year shows an overall absence rate of 7.9 per cent, whereas the rate was below 5 per cent in the three autumns immediately before the pandemic (4.9 per cent in 2019, 4.3 per cent in 2018 and 4.4 per cent in 2017).

A lot of this latest absence is down to illness. Specifically, the rate of persistent absence - the proportion of pupils missing one in 10 sessions or more - was a quarter (25 per cent) in autumn 2022, but over half was because of illness alone (13.2 per cent).

However, the rate of unauthorised absences has risen, to 3.1 per cent in mainstream secondaries and 1.5 per cent in mainstream primaries last term - up from 1.6 per cent and 1 per cent in 2019.

This data has limits, experts warn, owing to discrepancies over how certain reasons for absence are reported and coded.

What is clear, however, is that each type of absence is higher than it was pre-pandemic, with the reasons behind this being multi-faceted.

Illness anxiety ‘heightened’

In its submission to the Commons Education Select Committee inquiry into persistent absence earlier this year, the Association of School and College Leaders explains that, during the pandemic, parents had “obeyed strict instructions not to send children into school if they have any sign of illness”.

Heads say switching this mindset off has not been easy.

Yvonne Brown, CEO at the Leading Learners Multi-Academy Trust - a trust of four primaries in Yorkshire and Manchester - warns that health anxiety “is much more heightened post-pandemic”, while Kate Brunt, CEO at The Rivers CofE Multi-Academy Trust - consisting of 15 primaries - says society as a whole is now “more wary” and perhaps even “less resilient”.

Parentkind CEO Jason Elsom agrees it is possible that some parents “remain more risk-averse in instances where their child is ill, and keep their child home rather than risk spreading infection”.

There is clearly a middle ground between telling parents to ignore illness altogether and avoiding sending children in at the first sign of a sniffle. But Brunt says that, on sending a letter out to families trying to explain this middle ground, she met with pushback from parents who argued she was asking unwell children to attend school.

According to ASCL, she is not alone, with the union warning that changing advice on how to handle illness has led to “a confused and sometimes acrimonious” situation.

And while anxiety about illness is one significant issue, a broader increase in anxiety and mental ill-health has also been noted by those working in schools.

“The younger children were very small when the pandemic broke out, so there were a lot of separation issues. And there are some children who still really don’t want to leave their carer in the morning,” warns Brown.

Again, ASCL says this is a broader trend, with members “continuing to witness increased anxiety post-pandemic”, which is “having a significant ongoing impact on attendance”.

The impact of poverty

School leaders and unions have also warned that poverty - exacerbated by the cost-of-living crisis - is driving higher absence levels.

Rachael Howell, chief executive at The Stour Academy Trust, which runs eight primaries and secondaries across Kent, says that some parents may not send a child in “because they haven’t actually been able to wash the school uniform and they’d rather not send their child to school than send the child to school in dirty clothes”.

“A lot of our families are on pre-paid meters, and perhaps they couldn’t afford the electricity to run the washing machine,” she adds.

The NEU teaching union raises similar issues in its education committee submission, arguing that economic hardship can “affect the mental health of parents, making it harder for parents to engage in school activities and monitor and support attendance”.

Alienation from school is not just driven by economic factors, though.

The highest rates of persistent absence are seen among students of Irish Traveller heritage - at 66.5 per cent - but among this group, a majority (63 per cent) are eligible for free school meals.

Professor Kalwant Bhopal, from the Centre for Research in Race and Education at the University of Birmingham, has conducted research specifically with Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children. She cites two main reasons for poor attendance and high dropout rates from education: experiences of racism and the sense of not feeling represented in the school curriculum.

“It could be that many young people are questioning the value, in a sense, of schooling”

Indeed, curriculum challenges are cited widely by education leaders as a reason for high absence.

The NAHT school leaders’ union’s submission to the education committee says that “heightened focus” upon academic attainment within school performance measures, and funding pressures, has “helped drive a narrowing of the curriculum”.

“It is, therefore, unsurprising that pupils who imagine a future beyond school outside an academic sphere may feel less connection to their learning,” it adds.

Lee Elliot Major, social mobility professor at the University of Exeter, concurs.

“Does the current curriculum attract people from all backgrounds?” he asks. “It could be that many young people are questioning the value, in a sense, of schooling, particularly in areas where there might not be jobs.”

What are schools doing?

School leaders are trying their best to think creatively about ways to support children to attend, particularly in terms of the curriculum.

“You need to make sure that your curriculum is engaging and exciting, so children want to come to schools and battle parents to get in,” says Brown.

She aims to ensure that the curriculum “sings” to children, so they give their parents “aggro” to make sure they are in. This might include working on an exciting art and design project or inviting an author into classes.

Brunt agrees. “If you’ve got a badgering five-year-old or six-year-old saying they want to go to school, you’ll get them to school because, actually, that’s the easiest thing to do,” she says.

Strategically timetabling the subjects that attract pupils can also be a weapon in a school’s arsenal. “Standards in core subjects is a cornerstone, but do they always have to come into English first thing?” Brown asks.

“And some children excel at PE and don’t want to be off on PE day,” she adds.

There are other approaches being used by schools to boost attendance. For example, Brown says the mantra “make every day count” is on every newsletter her schools send out, while the schools also run breakfast clubs and coffee mornings for parents.

Under an initiative called The 25-day Challenge, pupils attending consecutively get a prize, and their parents are entered into a prize draw.

Brunt also stresses the importance of providing financial support for parents. Her schools in deprived areas offer food from Tesco three times a week, so parents know this is available to them if they come in to the school.

And Howell adds that her schools have staff who come in early and walk around the housing estates by the school and collect pupils.

Various research projects have also promoted further good practice for schools.

Elliot Major has previously described how personalised text message campaigns for parents could be a “potential low-cost approach for improved school attendance”.

DfE ‘couldn’t really find anything we weren’t doing’

There are also multiple schemes being run by the DfE to try to help schools.

An attendance adviser project announced in 2021 and a pilot of attendance mentors, currently underway in Middlesborough, are two such examples of these, along with an attendance dashboard project.

Trevor Dunn, head of access to education at Middlesborough Council, says a DfE adviser provided the council with a self-evaluation tool, which helped to “frame” its approach to tackling absence.

“It allowed us to take a big problem, which attendance is, and asked leading questions to direct our thinking,” he says.

Others, while not saying the advice was unhelpful, suggest it was severely limited.

Howell describes her interaction with an attendance adviser who worked with a school within her trust on the Isle of Sheppey last year as “positive”, but adds: “She couldn’t actually find much that we weren’t doing.”

“Each Ofsted [inspection] the school has received says that attendance is not high, and yet everything seems to be in place,” she says.

Howell also challenges what she describes as a focus on data analysis, saying she doesn’t agree that it will help her settings.

And it is unclear whether the DfE’s help is reaching the schools that need it most (see box, below).

Limits to what schools can achieve

Education leaders say more cash would certainly help schools to improve attendance.

Support teams have been depleted in many local authorities, leaving many smaller primaries reliant on heads and deputies to carry out attendance work. Ideally, schools would have access to family liaison practitioners, says Elliot Major.

But even this will not tackle wider societal problems that need to be dealt with by other arms of the state.

Elliot Major sums up the problem: “The question is, where does it stop for schools, where does the day end?”

This is a question leaders are battling with, and, for many, the answer is constantly changing.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters