Schools White Paper: 5 key claims fact-checked

The Schools White Paper published by the government this week contains many notable plans - from enforcing a minimum 32.5-hour school week to aiming to boost average GCSE grades from 4.5 to 5 for English language and maths.

Underpinning these plans are bold claims that they will deliver many benefits to pupils and the nation as a whole, and claims that existing policies have delivered many positives as well.

Tes has picked out five of the most notable claims put forward by the Department for Education to see if they stack up - and our findings are interesting...

Fact-checking the Schools White Paper

1. Will boosting GCSE scores add £34 billion to the economy?

One particularly bold claim is in relation to the ambition to increase the national average GCSE grade in both English language and maths from 4.5 to 5, which the government says will be worth an estimated £34 billion to the economy.

This would be for the cohort that takes its exams in 2030 - and the benefit would then continue each year after, so it would have a considerable economic impact. It’s a big number and the government has been happy to show its working on this, with a methodology document breaking down where this figure comes from.

It explains that, based on research conducted by itself and published last year on the lifetime earnings attributable to exam outcomes, a one-grade improvement in maths is associated with an additional discounted lifetime return of £14,500, and in English the return is £7,300.

As such, a 0.5-grade increase would be worth £7,250 for maths and £3,650 for English - equating to around £11,000 additional earnings.

This, though, is then brought down to £9,800 due to an economic measure called ”discounting”. It effectively means that the time it takes to wait for a financial investment to have a return reduces its impact.

Then by multiplying £9,800 by 613,000 - the number of students expected to take their GCSEs in 2030 - this equates to a total boost of £6.05 billion.

Luke Sibieta, a research fellow at the Institute of Fiscal Studies, says this portion of the calculations is solid and based on “very good research”, and can be taken with good faith as being accurate.

“One can quibble with the precise method and there will always be uncertainty around individual estimates, but fundamentally they are likely to be in the right ballpark,” he adds.

Andrew Eyles, a research economist at the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE, agrees:” I think that’s pretty accurate, really. It’s the best way of kind of measuring what happens when people move up kind of a grade distribution [and] it uses the best data set.”

Of course, though, this is still a way short of the £34 billion figure. To get to this, the government says that we need to look beyond simple lifetime earnings and understand the impact that a higher-earning workforce has on the wider economy.

Eyles says doing this is fair and it is an important consideration in economic research into the benefits of a well-educated workforce.

“If you’re going to make an estimate on what are the benefits of increasing basic skills, you do need to account for the wider effect of education on society. It’s not enough just to say, ‘These people’s earnings are going to go up by X amount,’” he says.

So to work this out, the government used two recent research reports from the US - the first here, and the second here - that estimated the earnings loss to the wider economy through the lack of schooling during the pandemic.

The first estimated that it would be $14.2 trillion (£10.8 trillion) while the other said $2.5 trillion. By dividing these numbers to find a multiplier, you get a figure of 5.7, which the government used to multiply the £6.05 billion figure - arriving at £34 billion.

Sibieta says that while it is true that there will be wider economic returns from a boost in education, he is “less keen” on how they have arrived at this 5.7 multiplier to get to the £34 billion figure: ”I think this is extremely speculative [...] and a bit over the top.”

Eyles also says he thought this outcome harder to justify, explaining that there are so many different papers that attempt to put a metric on the value of education that any figure has to be taken with some caution.

“I think the issue is, they’re just two studies, basically. And there’s so many studies looking at these things and the estimates vary quite a lot,” he adds.

So while it is clear that boosting grades will have a positive economic impact on both an individual’s earnings level and wider society, the figure of £34 billion is certainly not one that should be seen as definitive.

2. Has the government narrowed the disadvantage gap?

Another notable boast in the White Paper is that the government has a successful track record of narrowing the attainment gap.

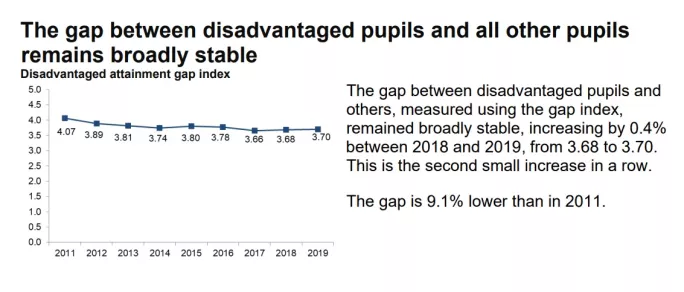

Specifically, it claims that in terms of the gap between students from disadvantaged backgrounds and their non-disadvantaged peers, there was a 12.8 per cent narrowing between 2011 and 2019 for key stage 2, and 9.1 per cent for KS4.

The basis for this claim is taken from the DfE’s own Disadvantaged attainment gap index - but talking to experts, it is clear that the numbers used don’t tell the whole story.

For example, Sibieta says that “all this narrowing of the attainment gap occurred between 2011 and 2014”.

Dave Thomson, chief statistician at FFT Education Datalab, adds: “Most of the reduction in the KS4 gap (8 per cent of the 9 per cent they quote) occurred by 2014.”

The DfE’s own data also reveals this to be the case, and, in fact, there has been a slight widening of this gap in the two years before the pandemic (see below from the government’s own publication).

Natasha Plaister, a statistician at FFT Education Datalab, says this makes the claim even less impressive.

“If you look at a different time frame, things look a bit different,” she says. “If you look at the three years before the pandemic, between 2017 and 2019 the gap at KS2 only narrowed by 3.0 per cent and at KS4 it actually widened by 1.1 per cent.”

However, it does seem that the government’s claim that it has narrowed the gap since 2011 is - at least, based on the government’s own metrics - accurate.

But for Plaister the wider issue is that the numbers it is crunching aren’t reliable, as the eligibility for free school meals (FSM) has changed over the past few years, leaving a “question mark over how consistent the definition of disadvantaged pupils actually is”.

It’s a point that the National Foundation for Educational Research makes, too, citing its own recent research showing that changes to universal credit will make it hard to truly tell if movement in the attainment gap is being driven by changes to the composition of the disadvantaged group, economic conditions or genuine attainment changes.

“Going forward, we recommend that a more meaningful set of measures are needed to ensure that we can understand how the attainment of disadvantaged pupils is evolving over time,” adds NFER research director Jude Hillary.

3. Is the success of MATs being overstated?

It’s no secret that the government wants more schools to be in multi-academy trusts (MATs).

The Schools White Paper adds that the government wants most trusts to be formed of 10 schools or more, as this is where the best efficiencies start to occur.

Specifically, it says that trusts “typically start to develop central capacity when they have more than 10 schools” and that this scale allows them to “be more financially stable, maximise the impact of a well-supported workforce and drive school improvement”.

Furthermore, in a document published alongside the White Paper, the DfE says MATs are, on average, “less likely” than single-school trusts to have a current or predicted deficit, qualified accounts or financial concerns.

It adds: “On all those measures, trusts of 15-plus academies outperform other trusts on average.”

But the evidence the government has provided to back up its claims has been criticised by experts - as we reported in a separate story earlier this week.

For example, Jenna Julius, a senior economist at the NFER, says there is “no conclusive evidence” that MATs are more effective than maintained schools or single-school trusts at managing their finances and that the DfE’s claims are “difficult to evidence”.

Meanwhile, the Education Policy Institute (EPI) think tank says prior research it has done on the impact of Covid on school finances shows that bigger trusts are not always more resilient in the face of financial pressures or that their attainment outcomes are stronger.

“Our research has generally found little difference between the attainment outcomes of academies and local authority-maintained schools,” says Jon Andrews, head of analysis at the EPI.

As such, it seems that the case for the power of trusts, at least in the White Paper, may have been overstated.

4. Is £30,000 for new teachers one of the ‘most competitive’ starting salaries?

Earlier this year, the DfE announced its commitment to a starting salary of £30,000 by 2023-2024 - and this plan appears in the White Paper, alongside the statement that it is a wage “amongst the most competitive in the labour market”.

While few would argue that a £30,000 salary is not “competitive”, the claim that it is among the “most competitive” in the labour market may raise eyebrows.

However, it seems that it may be a reasonable claim. For example, a report from an independent research company focused on the graduate market called High Fliers recently found that graduate starting salaries at the UK’s “leading graduate employers” is £32,000.

Given that this is based on a selective group of companies with specific graduate recruitment schemes, the fact that you can start on a £30,000 salary as a state-funded teacher does seem pretty competitive.

Elsewhere, job comparison site Glassdoor lists the average graduate salary based on survey data from 1,562 salaries submitted as £29,293. It’s not the most empirical data set but it again shows the new salary is going to stand up against other organisations.

Meanwhile, the government’s own data for working-age graduates from 2020 reveals that the median salary was £35,000 - so clearly there are many more people who do earn more than the £30,000 figure, but it’s not too far off the median.

So while a claim that the new starting salary is among the “most competitive” is open to debate, as clearly you can earn more elsewhere, the plan will definitely bring starting salaries to a level that may make the profession more appealing to those considering a career in the sector - so a little hubris seems forgivable.

5. Will enforcing a 32.5-hour school week stop lost teaching time?

Finally, perhaps the easiest “headline policy win” of the White Paper for the government came from its plan to require all schools to ensure a minimum 32.5-hour week.

This was put forward as being required to stop some schools from effectively depriving their pupils of up to two weeks’ additional learning a year if they fall under this threshold by 20 minutes. However, the reality is more complicated.

As Tes columnist Laura McInerney points out from Teacher Tapp data, many schools that do run below this 32.5-hour figure do so because they have shorter lunchtimes or breaktimes - not because they reduce teaching time. Conversely, for many that are over this threshold, it is because they have longer lunchtimes.

McInerney notes that there are some rare examples of primary schools having “long-ish lunch breaks that still didn’t hit the 32.5-hour week target” - suggesting they may be losing teaching time for pupils. But she says that “data would suggest it’s very unusual”.

Primary head Michael Tidd also says he worries the policy will lead to schools simply elongating breaktimes to hit the target.

“We’ll have schools that have spent time consulting with families about shortening their breaks - to fit transport needs or to align with neighbouring schools - having to stretch them again so they can stick the sentence on their websites, too,” he writes.

While enforcing a 32.5-hour week may bring consistency to the sector, the idea that it will boost teaching time to any meaningful degree seems questionable.

But, given that many have argued that longer breaktimes are important for socialistation and wellbeing, perhaps there will be an unintended benefit from this proposal anyway.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters