The number of pupils who were severely absent and the number of days missed through unauthorised holiday rose sharply in England last year, new Department for Education data shows.

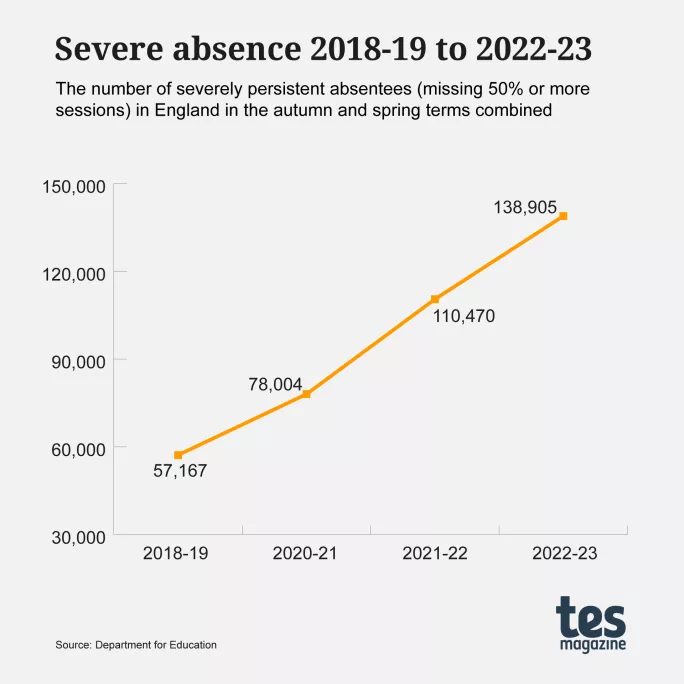

A total of 138,905 pupils missed 50 per cent or more half-day “sessions” - and were therefore classed as “severely” absent - in the autumn and spring term 2022-23 combined, according to figures published today. This was up from 110,470 the previous year and far above the 57,167 recorded in 2018-19.

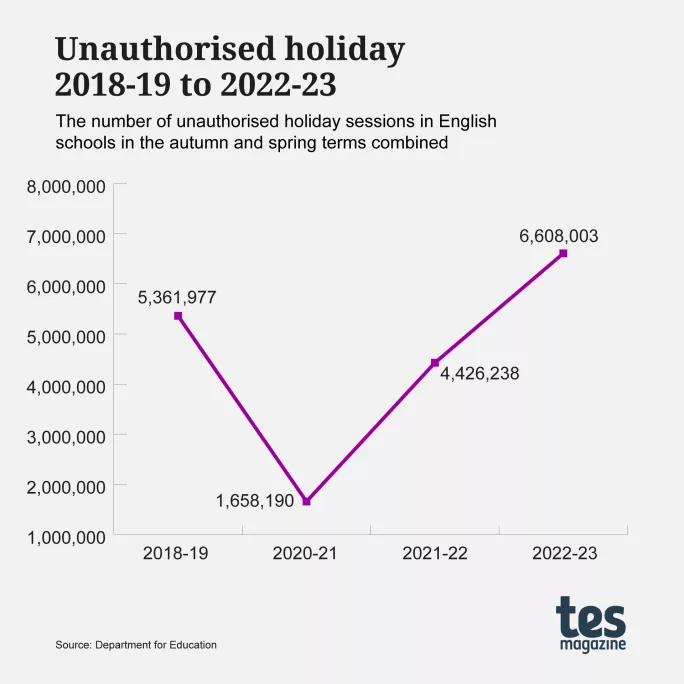

In state primaries, secondaries and special schools, the number of half-day sessions missed due to unauthorised holiday also rose year-on-year by more than 2 million.

Comparing the autumn and spring terms in 2021-22 with those in 2022-23, the number of unauthorised holiday sessions recorded rose from 4,426,238 (0.2 per cent) to 6,608,003 (0.4 per cent) - much higher than the 5,361,977 (0.3 per cent) recorded pre-pandemic.

Severe absence rose at a higher rate in secondary schools, increasing from 2.5 per cent to 3.1 per cent year-on-year, while the figure rose from 0.6 per cent to 0.7 per cent in primary schools.

And today’s data reveals that while overall absence across all settings fell marginally from 7.4 per cent, it rose in pupil referral units from 37.4 per cent to 40.7 per cent year-on-year (up from 34.4 per cent pre-pandemic).

And the proportion of “persistent” absentees in pupil referral units - those missing 10 per cent or more sessions - exceeded eight in 10, rising to 81.2 per cent, up from 78.3 per cent in 2021-22 and 72.2 per cent in 2018-19.

Across all settings, more than one-fifth (21.2 per cent) of pupils were persistently absent across the autumn and spring terms 2022-23. This was down from 22.3 per cent in 2021-22, but still double the 10.5 per cent recorded in 2018-19.

However, government figures show that persistent absence fell from 24.2 per cent in the autumn term to 20.6 per cent in the spring term alone in 2022-2023.

While the overall absence rate for autumn and spring fell between 2021-2022 and last year, the rate rose in Year 1 and below, and in Year 9 and 10.

Concerns over absence have spiralled since the pandemic and the government has overseen an expansion of a pilot scheme involving attendance hubs and attendance mentors.

However, some union leaders have criticised the hubs programme, claiming that the measures only “scratch the surface”, adding that the government will need to put more funding into its attendance drive if it is “serious” about solving the problem.

Absence crisis ‘could scar children’

Commenting on today’s figures, Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at the University of Exeter, said that it was ”increasingly clear” that the crisis of persistent absence would ”not be solved by existing efforts to improve school processes for getting children back into the classroom”.

He said that a bigger debate “about the fundamental factors fuelling the widespread rise in absenteeism” was “urgently” needed”.

“A whole generation of children risk being scarred if they never get back into the habit of regularly attending school,” he added.