Teacher pay offer: is it affordable for schools?

The government said the new teacher pay offer it announced this week is “fair and reasonable”, but the deal has been condemned as “insulting” by the NEU teaching union.

The question of whether it is affordable within school budgets has also polarised policymakers, experts and unions, with one headteachers’ leader accusing the education secretary of “cherry-picking information” and using “propaganda” in an email setting out how schools should be able to afford the pay rise.

So what are the facts behind this war of words about how the offer will be funded and whether heads have enough cash to pay the bill?

What is the teacher pay offer and how is it funded?

The pay offer put on the table this week includes a one-off payment of £1,000 to teachers this academic year, on top of the 5 per cent rise most teachers received in September.

It also includes an average pay rise of 4.5 per cent for 2023-24.

A new government grant will fund this year’s £1,000 payment, as well as 0.5 per cent of next year’s pay rise.

“To ensure the pay offer is fully funded, we will provide further funding of around £620 million in 2023-24 for the additional 0.5 per cent...We will also provide a further £150 million in 2024-25 to schools to cover the ongoing costs of the pay increase,” education secretary Gillian Keegan said in an email to heads yesterday.

The remaining 4 per cent of next year’s pay rise will have to be met via existing budgets.

Asked if the pay offer was “fully funded” at a meeting of the Treasury Committee yesterday, chancellor Jeremy Hunt said that there would be “no reduction” in frontline services as a result of the award - and other public sector pay awards.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, challenged this, saying it was “not based in reality”.

So is the rise affordable for schools?

The NEU has described the pay rise as “not fully funded”, meaning that schools will have to find money from their existing budgets - which it said would result in cuts.

The union said its own analysis suggests that between two in five (42 per cent) and three in five (58 per cent) of schools would have to make cuts next year to afford it.

But the Department for Education said that the rise is “judged to be affordable” for schools. It points to the extra £2 billion being given to schools - above previously agreed funding - in 2023-24, as well as in 2024-25, set out in the Autumn Statement.

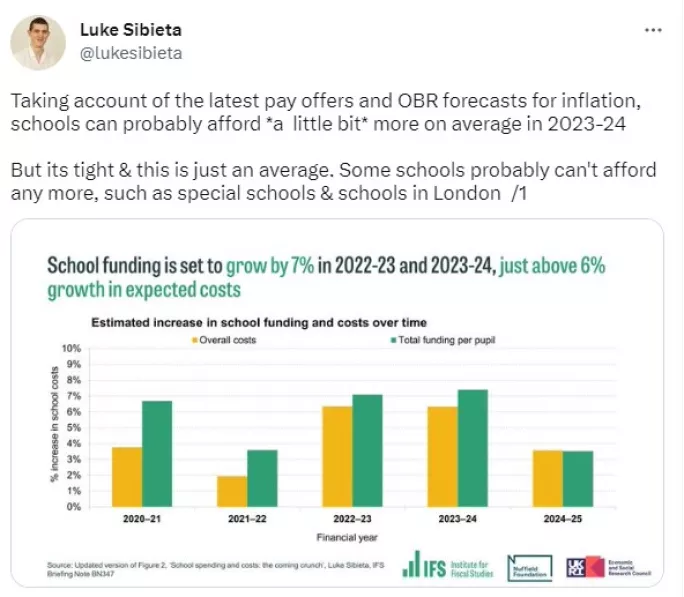

Luke Sibieta, a research fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said that school funding per pupil is likely to grow by about 7 per cent in both 2022-23 and 2023-24, and estimates that school costs are likely to grow by about 6 per cent in both years.

He said this means that schools “could potentially absorb a small amount of the higher pay offer for teachers”.

So does this mean that the DfE is right?

Mr Sibieta pointed out that the IFS figures are “just an average” and that some schools “will be seeing costs growing faster than funding”, such as special schools with heavier reliance on support staff, and schools in London, which are not experiencing funding growth at such a rapid rate.

Support staff have been offered a £1,925 pay increase from April, which equates to a 9.42 per cent cost increase for the lowest paid staff - though the offer has not been accepted.

Special schools, and schools with higher numbers of pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), will generally have more members of support staff, so are likely to have less headroom, if they have to fund these increases without extra money.

This mixed picture is also highlighted by Stephen Morales, CEO of the Institute of School Business Leadership (ISBL). “It will be affordable to varying degrees,” he said, but “it won’t be affordable to all schools”.

The actual cash terms impact for each school will depend on their staff mix, and where they sit on the pay scales, he added.

Will falling energy prices give schools more headroom?

The DfE said it expects 4 per cent to be affordable “because energy costs are forecast to fall at a faster rate than previously expected”.

In its submission last month to the School Teachers’ Review Body, which recommends teacher pay in England, the DfE wrote that a rise of 3.5 per cent would be “manageable” within schools’ budgets next year, on average.

But this is 0.5 percentage points lower than they are now being asked to fund.

The DfE’s submission added: “Different energy scenarios mean that more headroom could be available than the 3.5 per cent currently estimated. This could allow for additional investment in areas which benefit pupils, including, for example, a higher pay award.”

However, it conceded in the same evidence that costs were “currently particularly difficult to forecast with confidence at both a national and school level”, and that exact situations would “vary considerably” from setting to setting.

Mr Morales said the affordability of pay rises will depend on when energy price drops kick in for each school.

While schools on flexible energy deals, or those with deals due to expire soon, may see some easing in prices in the near future, the same may not be true for those on fixed-price deals.

Chris Jermy, head of education energy solutions at procurement firm Zenergi, said that the company was seeing contracts coming in at around 25p/kWh on electricity and 6p for gas as things stand, “which is saving schools significant sums”.

But similar to Mr Morales, he said there would be differences between schools caused by financial year differentials, contract renewal dates and purchasing strategies.

The DfE also accepted in its evidence that there is incomplete data on the energy deals that schools are on, admitting it “does not hold information on individual schools’ energy contracts and usage; this, combined with future price uncertainty, means it is not possible to produce an exact estimate of schools’ energy costs in 2023-24”.

Tes asked the DfE for its evidence on the affordability of the new pay offer based on energy price forecasts but did not receive a response.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article