What will teacher strikes look like?

The latest crop of education ministers to enter Sanctuary Buildings are in for a bumpy ride this winter.

They inherit not just a policy headache in the form of the decimated Schools Bill but a looming national teacher strike over pay - with a new prime minister who’s talked about tough decisions on public spending and fiscal discipline.

Last week both the NASUWT and NEU teaching unions began to ballot members on strike action over pay and funding.

And the NAHT school leaders’ union is set to follow suit after announcing its intention to ballot members on strike action over pay for the first time in its 125-year history.

It looks highly likely that educators will join with other public sector workers gearing up for industrial action next year.

- Industrial action: Political chaos will lead to teacher strikes, warn school leaders

- School leaders: Union to launch formal ballot on striking over pay

- NASUWT: Most parents “would back” teacher industrial action

- Latest: Teaching unions move closer to strike action as ballots announced

But what could this action look like in schools? What are the end goals of the unions? And are they likely to achieve them?

And what does all of this mean for those school leaders trying to delicately juggle support for the cause with meeting their pupils’ needs?

As staff cast their votes, Tes takes a look at how teacher strikes have played out before - and what impact they might have this time around.

The last big teacher strikes

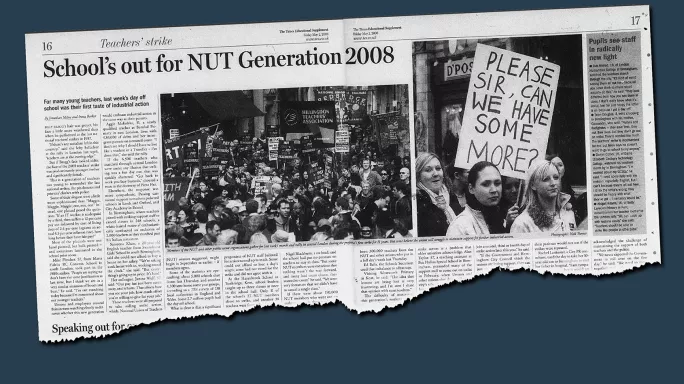

The last big industrial action was six years ago, when the NUT (which predated the NEU) led a day of walkouts in July 2016 making a number demands, including better funding for schools; a guarantee on terms and conditions for teachers in all types of schools, including academies; and a reduction in workload.

Eight years earlier, 200,000 teachers had walked out for a day over the government’s refusal to raise a pay offer of 2.45 per cent.

The NUT sent out another strike ballot later that year, but decided not to push ahead owing to a lower turnout and the deteriorating economy.

It would be fair to say that neither action achieved all of its aims. Indeed, one multi-academy trust chief tells Tes he has seen industrial action take place many times and never once seen any success in terms of changing the government’s mind.

However, this time grievances are more streamlined, with the NEU and NASUWT both demanding a fully funded above-inflation pay rise, while the NAHT wants what it calls a suitable agreement on pay and funding.

Lord Knight, Labour’s schools minister at the time of the 2008 teacher strikes over pay, and chair at E-ACT multi-academy trust, says “the current context is radically different”.

“The cost-of-living pressures are very real for teachers and schools,’’ Lord Knight says.

“The current context is radically different”

And public support may be with the unions: a survey from the NASUWT earlier this month found that more than six in 10 parents would support teachers taking action if they were given a below-inflation pay rise.

Jonathan Simons, partner and head of education practice at Public First, thinks there will be “a lot of public sympathy for teacher, and especially headteacher, strikes”.

However, given the current financial situation with spending cuts reportedly on the cards, the Treasury “will be…concerned, not just with public sector pay control in general but showing the markets they can stick to their plan to reduce debt”, he adds.

But for some leaders and teachers, industrial action is simply a welcome chance to have their voices heard.

Dan Morrow, chief executive officer of Dartmoor Multi-Academy Trust in Devon, says he would walk out with his staff.

“I think enough is enough, and I will support colleagues in that, and I will go out on strike myself,” he says.

Morrow adds he would be “very open” with parents and carers if strike action went ahead.

How would strikes impact on vulnerable pupils?

Morrow admits it is a concern that staff would have to choose between helping vulnerable pupils and not breaking picket lines.

But vulnerable children are already being “failed”, he feels, due to “unfunded pay rises, a demoralised and depleted workforce and a decade of real-terms cuts to education”.

However, Rob McDonough, CEO of the East Midlands Education Trust, is more cautious. Having worked in the profession since 1986, he warns that industrial action “is something that can be incredibly disruptive to schools and the life chances of young people”.

He hopes “both sides’’ can “reach an agreement to avoid disruption in schools, which can have such a profound impact on the lives of children and also inconvenience parents”.

Another school leader acknowledges the risks that strikes would pose to young people “either by not having free school meals or by being in the community”, and the impact on pupils’ learning.

Disruption in schools “can have such a profound impact on the lives of children”

Decisions over sending children home to learn remotely would involve looking at “safeguarding first” and “education second”, he says.

“I can see there being difficult decisions around protecting examination year groups and then protecting the most vulnerable,” he says.

He adds that “regardless” of teachers’ views on strikes, they will be “committed to make sure they don’t implicate young people”.

While any union needs to weigh up the impact of a loss of public services, schools are closely woven into the fabric of their communities, which creates a particular pressure. When train drivers go on strike “it’s anonymous”, the leader explains, whereas in education, the “parents are going to know which teachers are on strike”.

For its part, the NAHT union says members are “keen to ensure that our actions are directed at government and not at children”.

In Northern Ireland, where NAHT action has already started, every safeguarding-related activity is “ringfenced…as being work that cannot be interrupted”, a spokesperson said, adding that this would include supporting children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND).

And Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), says that, while it is uncertain whether industrial action will go ahead, “schools will put plans in place around issues like safeguarding and support for vulnerable children”.

In some education settings, deciding to strike may be especially “painful”, according to one special school leader.

The leader, who does not wish to be named, says: “Students I work with require high degrees of routine, organisation, structure.

“That’s always been a huge factor in my decision-making process”.

In his experience, the “emotional side of that decision” has prevented “quite a few teachers” from walking out before.

However, he intends to take part in strike action if it goes ahead this time around, saying that the “appetite for political change in the country has never been more acute in recent history than it is now”.

Both the NAHT and NASUWT are balloting over strikes alongside other industrial action, while the NEU is balloting only over strike action.

The picture for the ASCL is less clear, following mixed results from its survey of leaders, with only half of respondents calling for an indicative ballot on strike action.

A mere 16 per cent responded to the survey, sent to 13,693 state school leaders on 31 August, when schools were still in the summer holidays.

Despite Tes’ efforts to confirm with the union what its current position is, the ASCL only says it is consulting generally with members.

Different kinds of industrial action

For NEU members, meanwhile, industrial action could happen from 30 January next year.

The parameters for “industrial action” are very broad, according to Siobhan Mulrey, senior associate solicitor at Irwin Mitchell.

For example, they could include “working to rule”, a “go slow” or a marking boycott. Mulrey thinks staff could also legally refuse to engage in Ofsted inspections, but says this has not been tested.

There are some limitations. “Inducing another person to breach their contract of employment” by asking them to strike would fall foul of the law, Mulrey says, as would enforcing union membership.

Mulrey also says there’s “nothing” within the Labour Relations Act to “prevent unions from carrying out strikes at the same time, “provided that each of those unions have properly balloted and carried out the strike action in a lawful manner”.

And she can see this happening, given that, outside of the education sector, trade union leaders are “already considering waves of synchronised strikes to cause maximum disruption possible”.

And Mulrey says it would “probably make sense” if unions did strike at the same time, avoiding multiple days of understaffing.

School leaders ‘left in the dark’

Ultimately, school leaders may not know what to expect ahead of time. One MAT chief who wishes to remain anonymous tells Tes that, in their experience, “headteachers are left completely in the dark” until the industrial action starts. This, they say, is because members of staff do not have to tell their employers they are striking.

The leader in Hertfordshire adds: “As the head, you’re given a directive from the Department for Education to keep the school open, but you have to take a risk assessment. But the information that you need to make that risk assessment you do not know until 10 or 15 minutes before the start of the school day.”

In 2016, he told his staff he would “appreciate” being told ahead of time to plan accordingly. “They don’t have to tell me, but, if you’ve got a good relationship, they might,” he says.

In September, multiple trade unions mounted a legal challenge against the government over a decision to allow agency workers to cover for striking teachers.

Dr Patrick Roach, general secretary of the NASUWT, which is launching its own challenge, called the new regulations an attempt “to further undermine and weaken the rights of all workers, including teachers, to take legitimate industrial action”.

Can schools use agency workers to cover staff on strike?

Tes understands that the government has acknowledged the application for a judicial review and the decision now lies with the courts.

But even if the new regulations are allowed to go ahead, there are serious doubts over how many supply staff would be prepared to cover teachers on strike.

So what impact could a national teacher strike have? A fully-funded, above-inflation pay rise seems unlikely in the current climate. But does that render the action futile, or is there a case for raising public awareness of the pressures that schools, teachers and leaders are under?

Strike or no strike, as schools are squeezed tighter and tighter, with grim recruitment figures and attrition rising yet again after the Covid years, the government may need to consider whether schools can survive without any additional help.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article