Exclusive: Just half of new primary teachers expected to find work

At this time of year new teachers yet to secure a contract are anxious - will they find work or won’t they?

Now, a new Scottish government analysis of teacher numbers - uncovered by Tes Scotland using freedom of information (FOI) legislation - is likely to heighten those fears, especially among primary staff.

The analysis predicts that only half of last year’s primary probationers will be in work in Scottish state schools by next month - be that on temporary or permanent contracts, working part-time or full-time.

Last year more than three-quarters of primary teachers (77 per cent) who had completed their probation the previous year were working in Scottish state schools by the September census.

- Background: By the numbers - teacher recruitment in Scotland

- Teacher recruitment: New teachers’ chances of a permanent job “plummeting”

- Analysis: Why are so many teachers struggling to find work?

The analysis - which was presented to the government’s Teacher Workforce Planning Advisory Group in March and published this week following the Tes Scotland FOI request - states: “We estimate that the proportion of primary teachers finding teaching employment will drop to approximately 50 per cent (down from 77 per cent in 2021).”

Responding to the figures, new EIS general secretary Andrea Bradley said it “beggars belief” that teachers are struggling to secure employment when education is supposed to be the Scottish government’s number one priority - and it is supposed to be “all shoulders to the wheel” so schools can recover from the pandemic.

New teachers unable to find jobs

She said it is “ridiculous” that so many highly skilled and trained people are “languishing on supply lists” or on temporary contracts.

“It does not make sense so many qualified teachers, who were encouraged to join initial teacher education and to stay the course during the pandemic, are now not able to find employment when - arguably, in the context of Covid - teachers are needed in greater numbers than ever before,” said Ms Bradley.

She accused the Scottish government of having “grand ambitions” for education but “skimping on education budgets”.

“Education cannot be the number one priority unless the investment matches the rhetoric - there is a lot of grandstanding when it comes to education but that’s not reflected in how funds are allocated or the constant fighting over budgets, and who will pay for what,” she said. “In the meantime, children and young people and teachers and the other staff that support them are left in the middle suffering.”

When Scottish teacher education students graduate from university, the majority join the Teacher Induction Scheme (TIE), which guarantees them a post in a school for a year so they can complete their probation.

The scheme - although now more than 20 years old - is still considered to be groundbreaking.

However, what happens to new teachers immediately after their probation year is increasingly attracting criticism.

The Scottish government has promised to increase teacher numbers by 3,500 during the course of the current five-year Parliament, but new teachers are increasingly likely to find themselves on temporary contracts - and now the Teacher Workforce Planning Advisory Group analysis suggests it will take a while for teacher numbers to start rising.

It says that in 2022 teacher numbers are expected to rise by just 362. They rose by 800 last year and are projected to rise by over 800 in 2023, 2024 and 2025. It says that this will therefore “likely have an impact on the proportion of the 2021-22 cohort of probationers who find teaching employment in 2022”.

The figures suggest that primary post-probationers have more to worry about than their secondary colleagues, and previous years’ figures also bear this out.

For example, while 77 per cent of primary post-probationers were working in Scottish state schools by September last year, that figure was 84 per cent for secondary post-probationers.

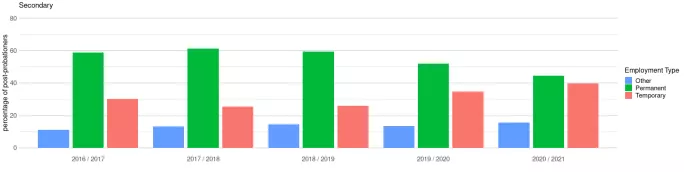

However, figures for both sectors are moving in the wrong direction and the analysis says “there are wide differences between the percentages of post-probationers in permanent posts, even amongst priority [secondary] subjects”.

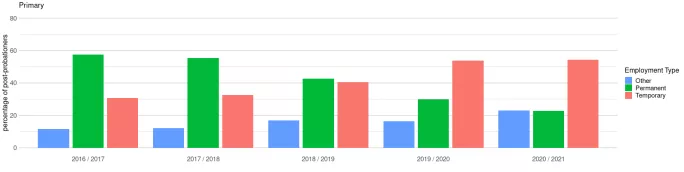

In the September following their probationary year, 58 per cent of the 2016-17 cohort of probationers had secured permanent roles. However, by the time the 2020-21 cohort of probationers had completed the teacher induction scheme and was looking for work, that figure dropped to 32 per cent.

Primary probationers have also become less likely to secure permanent posts over time than their secondary colleagues.

Among the 2016-17 cohort of probationers, roughly equivalent proportions had picked up secure jobs in their first year as fully qualified teachers: 58 per cent of new primary teachers had a permanent post by September 2017, and 59 per cent of new secondary teachers did. However, by the time the 2020-21 cohort of probationers was entering the jobs market, the picture was less positive. Just 45 per cent of secondary post-probationers were in permanent jobs by September last year, but for primary that figure was even lower at 23 per cent.

The graph below, from the Scottish government, shows the percentage of primary post-probationers by employment type for the first year following their probation only. The green bar showing the proportion in permanent posts reduces over time, while the pink bar showing those in temporary posts increases over time.

And the graph below shows the percentage of secondary post-probationers by employment type for the first year following their probation. Again, the proportion on permanent contracts is falling over time but is still far higher than in primary.

Now it has become normal to see new teachers taking to social media at this time of year to express their frustration. One primary teacher, who carried her probation out in Renfrewshire Council last year, said in a recent tweet that “trying to get a job in the teaching profession is honestly one of the most disheartening, awful experiences”.

Speaking to Tes Scotland, the 24-year-old said that she had only managed to get her name on supply lists. She said there were no permanent positions currently being advertised “unless you are willing to relocate to the Borders”, and that her lack of job security meant she was having to put her life on hold.

Nuzhat Uthmani, a Glasgow primary school principal teacher and co-founder of the popular Facebook group Scottish Teachers for Positive Change and Wellbeing, told Tes Scotland recently that recruitment was “the biggest concern by far among many colleagues, some who have been teachers for years and still are awaiting a permanent contract”.

She said that universities needed to be more upfront about the recruitment crisis, and called for local authorities to stop “using probationers as cheap labour to cover posts year on year, instead of giving permanent contracts to more experienced teachers”.

A spokesperson for the Scottish Council of Deans of Education (SCDE) said student teacher recruitment targets are set by the Scottish Funding Council.

However, the spokesperson said that it was the SCDE’s aspiration “that our student teachers, without exception, will secure employment as teachers following their probation period”.

The spokesperson added: “Where this is not happening, we stand ready to do all that we can to alleviate any issues so that Scotland can retain all its talent.”

The Association of Directors of Education in Scotland (ADES) said that some teachers would be picked up for jobs after census day - and also in their second and third year in teaching. ADES also pointed out that the primary school roll peaked in 2017, which means “fewer vacancies in the system”.

Tes Scotland reported in December 2020 that the Scottish government had been advised to scrap the most popular route into primary teaching - the one-year postgraduate route - from 2021 to 2027 because the primary school roll was expected to fall.

The government did not follow that advice and since then it has committed to policies that will require more teachers, including its promise to increase teacher numbers by 3,500 but also to reduce class-contact time.

It seems likely, therefore, that new teachers will secure jobs eventually but that will be cold comfort for those who need a steady income now.

A Scottish government spokesperson said: “While local authorities are responsible for the recruitment of their staff, we have taken action to support councils to recruit permanent teachers.

“Over the course of the pandemic, we have provided £240 million of additional investment, over two financial years, for the recruitment of additional education staff. This has supported the recruitment of additional staff and there are now over 2,000 more teachers in Scotland’s schools than before the start of the pandemic in 2019.”

The spokesperson added: “Last August we announced that further additional permanent funding equating to £145.5 million per annum will be baselined into the local government settlement from April 2022.

“This will ensure sustained employment of additional teachers, while meeting local needs and benefiting Scotland’s children and young people.”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article