GCSE and A level results 2021: What did teachers learn?

This week’s GCSE and A-level teacher-assessed results have seen higher grades at the top end, with a leap in the proportion of As and A*s awarded at A level.

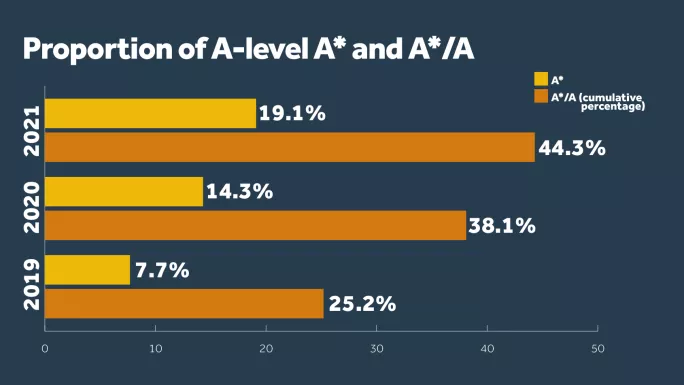

In England, nearly 1 in 5 (19.1 per cent) of entries were awarded an A* grade, while more than two in five (44.3 per cent) were awarded an A or A*.

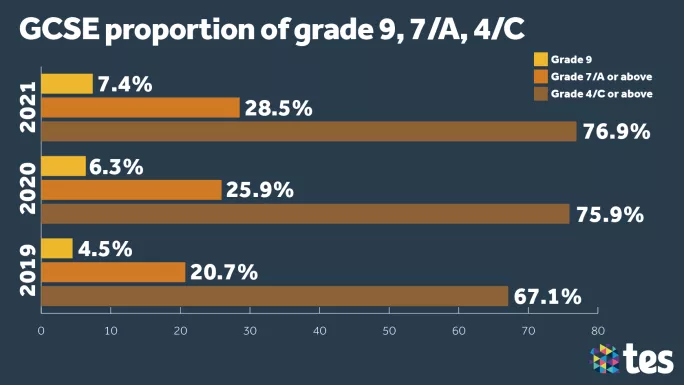

And at GCSE, 28.5 per cent of entries were awarded a grade 7/A or above, while 7.4 per cent scored the top grade of a 9.

More on this year’s GCSE and A-level results:

- A levels 2021: Results at a glance

- GCSEs 2021: Results at a glance

- GCSE resits 2021: More students achieve grade 4

- GCSE results 2021: ‘No long-term teacher assessment’

Here’s what we learned from results this week:

1. Did teacher-assessed grades ‘bake-in’ inflation?

At A level, results at the top two grades were even higher than in 2020, although a relatively smaller rise across the board was seen for grades awarded C or above, with an increase of 0.7pp to 88.2 per cent. The pass rate from A*-G dipped by 0.2pp to 99.5 per cent.

There are concerns that this level of inflation will now be “baked in” to the system, making it harder for universities to select applicants based on ability.

Attention is now focused on how grading standards might change for the 2022 cohort to deal with this, with possible plans for a new numerical grading system at A level, a phasing back to 2019 distributions over a number of years, or, less likely, a sudden jolt back to 2019 within a year all currently under discussion.

Within the education sector, however, some school leaders and experts have challenged the narrative around inflation.

In our Tes expert panel discussion of the A-level outcomes, Alison Peacock, of the Chartered College of Teaching, said we should “resist talking about grade inflation” as results are not comparable with other years.

But Jon Coles, chief executive of the United Learning trust, said: “Frankly, I think we probably should talk about grade inflation because it’s quite clear that the standard of this year hasn’t been the same as in other years.

“That’s not the fault of the teacher and it’s not the fault of the young people who’ve worked extremely hard and faced severe difficulties. But we have to remember that there are other cohorts of young people who are also affected by this year’s grading. And they have faced a different standard and will be, to a significant extent, in competition with this year’s group of young people.

“And when we’re thinking about fairness and equality, of course, first and foremost, we think about this year’s cohort. But we have to think about fairness and equality with previous cohorts and with future cohorts as well.”

2. Did cancelling exams widen inequality?

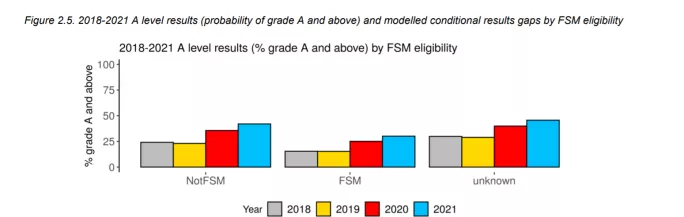

A-level results this year do show a widening gap for disadvantaged pupils and their peers at the top grades.

Ofqual’s equalities analysis says that the gap between pupils achieving the highest grades with unknown free school meals eligibility, versus pupils who are not eligible, has widened by 4.11pp since 2020.

And for the probability of attaining an A and above, the gaps indicating lower outcomes for black African, black Caribbean, and mixed white and black Caribbean candidates relative to prior-attainment-matched white British candidates have widened by between 1.85 and 2.97pp since 2020.

The report also finds that longstanding gaps “indicating lower outcomes of black candidates, FSM candidates, and candidates with a very high level of deprivation” have widened by 1.43, 1.42 and 1.39pp respectively.

And gaps between boys and girls, and between pupils with special educational needs and disability (SEND) and non-SEND candidates, widened, according to Ofqual’s data. In 2019, boys and pupils with SEND had higher grades than prior-attainment-matched girls and non-SEND candidates, but this was reversed in 2021.

In Tes’ expert panel, Zubaida Haque, former director of The Runnymede Trust, said: “If there’s one thing we know about the pandemic, is that it has had a disproportionate impact on those from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

She added: “We know that with A-level students from disadvantaged backgrounds, quite a few of them have also had to work to help their parents because of the impact of poverty.”

At GCSE, Ofqual said that there has been a slight widening of the “long-standing results gap” between students in receipt of FSM and those who are not, by around one-tenth of a grade compared with 2019.

And adjusting for prior attainment, results also show a slight rise in the gap between white and Gypsy and Roma students, by a fifth of a grade.

At grade 7 and above, “longstanding gaps indicating lower outcomes of FSM candidates, SEND candidates and male candidates relative to prior-attainment-matched candidates of their respective reference group, have widened by 2.27, 2.00 and 2.13 percentage points respectively”.

Natalie Perera, chief executive of the Education Policy Institute, told our expert analysis GCSE panel: “The fact that we are still seeing lower grades or widening of the gap for poor children, for black children, does suggest to me that this isn’t the system that we want in its entirety in the future.”

3. Why did more students achieve top grades in 2021?

The number of students receiving grade 9s across the board in GCSE has risen sharply over the course of the pandemic.

A total of 3,606 students achieved the feat this year, compared with 2,645 in 2020 and 837 in 2019.

Overall, 7.4 per cent of entries were awarded a grade 9 compared with 6.3 per cent last year.

This was predicted by Ofqual chief regulator Simon Lebus and chair Ian Bauckham earlier this year, who both said that under a teacher-assessed grading system, all pupils in a class with the potential to achieve a grade 9 would secure one, whereas in an exam year, some pupils might have a bad day and under-perform.

Some school leaders have said it is unhelpful to talk of grading in terms of inflation. Steve Chalke, founder of the Oasis Charitable Trust, told our expert panel: “I’m really concerned about the overuse of the phrase ‘grade inflation’.

“I think that’s very demeaning for young people, I think it’s unhelpful and it’s insulting, actually, for us to be talking about grade inflation at the very moment we’re trying to support young people who’ve lived through these last two years.”

But Mr Coles told our A level panel: “So we’re at roughly 45 per cent A and A*. I don’t think that’s a good place to be.

“And I think it’s a consequence of a system which wasn’t well designed and could have been better designed.”

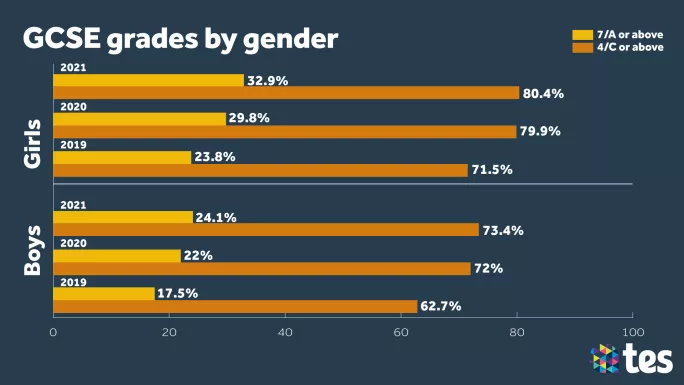

4. Does teacher assessment favour girls?

The proportion of girls’ entries awarded grade 7/A or above in GCSE this year was 32.9 per cent compared with 24.1 per cent for boys. This widened the gender gap at the top grade by 1pp to 8.8pp.

But the gender gap narrowed at grade 4/C, with 73.4 per cent of entries from boys and 80.4 per cent of entries from girls achieving a GCSE pass, a gap of 7pp compared with 7.9pp last year.

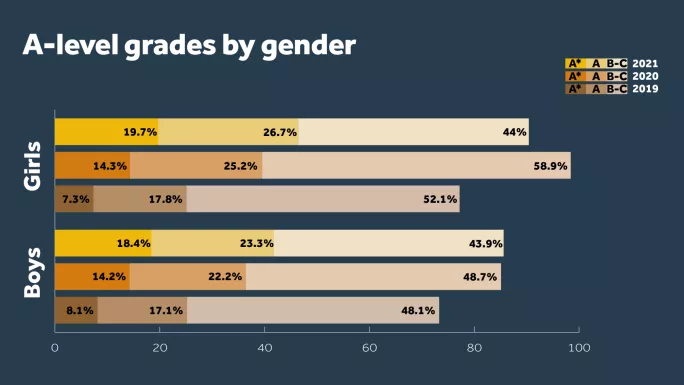

At A level, at the top grade, 19.7 per cent of girls were awarded an A* compared with 18.4 per cent of boys - a reversal of the gender gap seen in 2019, when more boys were awarded A*s.

In 2019, the last year when exams went ahead, 8.1 per cent of entries from boys achieved an A* compared with 7.3 per cent for girls.

At A*/A, girls increased their performance on the previous year by 7pp compared with 5.4pp for boys.

And girls’ A* rates increased by 5.3pp, compared to boys at 4.2pp.

Barnaby Lenon, chair of the Independent Schools’ Council and a former Ofqual board member, told our expert A-level panel: “So the gap between boys and girls at the top end has widened and we’re not quite sure why that would be.

“Maybe because girls are better than boys during the course of two years. It might be something to do with subject choice, because one of the, I think, still most remarkable things about these results is the gendered nature of subject choice at A level.

“I mean, there are only a couple of subjects where boys and girls are roughly the same: geography is one, chemistry is one. But if you look at computing, 12,000 boys and 2,000 girls, or you look psychology - now the second biggest A level - 19,000 boys but 53,000 girls.

“In a world where all schools strive for gender equality, it is extraordinary that, at the ages of 15 or 16, these young people are still choosing subjects with gender very much in mind. I always find that extraordinary.”

And Ros McMullen, founding member of the Headteachers’ Roundtable, said: “Assessment in the round, clearly, I think...is very robust and it does give a much more rounded picture than the flash in the pan, the putting it out of the bag on the day, or, alternatively, the crash and burning on the day.

“And, of course, we do see that with kids, don’t we? We see the kids that crash and burn, and we see the kids that pull it out of the bag. Actually. it’s fairer to have this kind of in the round assessment.”

“However, what we can see quite clearly, I think, is something that we have always known in education, which is that that suits girls better.

“There is something around the pressure of ‘every piece of work I do counts’ - continuous assessment, that keeping it going all the time - that is particularly suited to girls, whereas the boys respond quite a bit better, I think, to pulling it out on the day. Now, that raises an awful lot questions for us.”

5. Why was there a North-South divide in A-level results but not GCSE?

At A level, figures published by Ofqual showed the North East of England was the only one of nine regions in England that saw the proportion of C grades and above at A level drop compared with last year.

In the North East, the percentage of pupils achieving at least a C grade or better at A level was down by 0.4 percentage points in 2021 compared with last year’s figures.

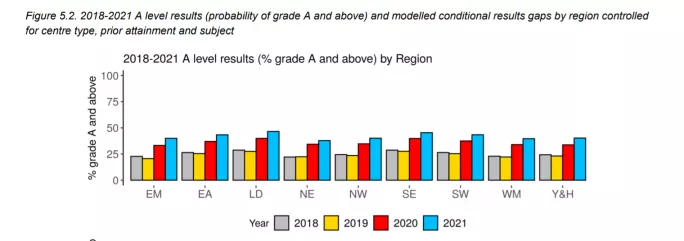

A-level results from 2018 to 2021 (probability of grade A and above) and modelled conditional results gaps by region

Equalities analysis by Ofqual shows that gaps indicating lower outcomes for A-level candidates in schools and colleges in the North East and the South West, relative to prior-attainment-matched pupils in the South East, have widened by 1.65 and 1.67 percentage points respectively since 2019.

But at the GCSE pass rate of grade 4 and above, the gaps indicating lower outcomes of candidates in schools and colleges in the North East and West Midlands, relative to prior-attainment-matched pupils in the South East, have narrowed by 1.76 and 1.02pp respectively.

Across England, every region recorded a year-on-year rise in the proportion of GCSE entries awarded 7/A or above, but London saw the biggest jump of all, up from 31.4 per cent to 34.5 per cent.

Yorkshire and the Humber saw the lowest percentage awarded 7/A or above (24.4 per cent), up from 22.3 per cent last year. Frank Norris, a former academy trust director who is now special adviser on schools to the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, said the figures demonstrate the need for action to be taken on a Covid education recovery plan that can benefit the North.

In terms of why there are larger regional gaps seen at A level, it is unclear why this might be - and headteachers have called for further investigation.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “Top grades at A level have risen in general but less so in the North East, where there is actually a small decrease at grade C and above. This pattern is at odds with GCSE performance, where grades have increased in the North East, broadly in line with the national trend.

“It is difficult to draw conclusions why this variation at A level has occurred without further analysis. We urge the Department for Education and Ofqual to look into this more closely to understand what factors may have impacted on A-level performance in the North East.

“Schools and colleges have worked incredibly hard in all regions to support their students through the pandemic. It is important to understand whether there are any wider issues that have affected performance so that appropriate support can be put in place.”

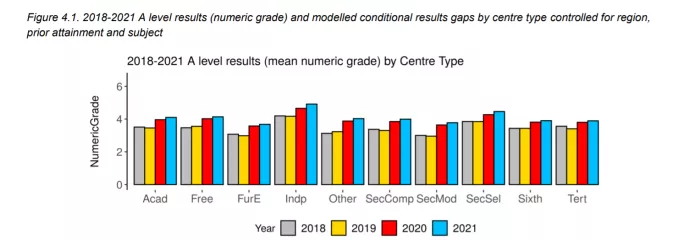

6. Did some types of schools perform better on average than others?

At GCSE, private schools and free schools saw the largest absolute increases in top GCSE grades this year. At grade 7/A and above, outcomes were higher than 2020 to the greatest extent in private schools, with a 4pp rise, while free schools also saw a rise in their proportion of top grades by 3.6pp.

But grammar schools outperformed private schools, with 68.4 per cent of entries scoring a grade 7/A or above, compared with 61.2 per cent of private schools.

At A level, the gap in the proportion of A*s awarded to private and state schools widened, with 39.5 per cent of independent school grades awarded A*s, up from 27.4 per cent in 2020 and 16.1 per cent in 2019, when national exams were last held.

Year on year, private schools have seen a 12.1pp increase.

Ofqual’s analysis found that the gap between secondary selective schools and academies had shifted from positive to negative. In 2019, candidates in secondary selective schools had higher outcomes than prior-attainment-matched candidates in academies, but, in 2021, this pattern reversed, representing a small change of 0.18 of a grade.

Long-standing gaps between private and grammar school pupils, and matched pupils in academies, narrowed this year.

Mr Lenon told our expert panel: “As far as independent schools are concerned, I mean...there is no very dramatic shift here.

“But it’s pretty obvious that independent schools, having better resources and, in particular, having better resources in the homes from which the children often come, not in every case, but often, did have very good online teaching right from the beginning, as did quite a number of state schools, but not all. And pupils in disadvantaged areas found accessing online teaching very difficult.

“And the system, this year, of teacher-assessed grades was designed to help compensate for that to some degree but it could never do that fully. And that’s what these results bear out.”

Ms Perera added: “I think there are two things. We ought to look at school type to understand why we are seeing some disparities but I think the hypothesis that we’ve seen already suggests there are two.

“One is the disparity between independent and state-funded schools could well be down to the learning loss that’s been inequitably distributed over the course of the pandemic.

“And also the point about being able to do large-scale moderation - I think that’s a very valid hypothesis that ought to be investigated.”

6. Which subjects were the winners and losers this year?

At A level, music saw the greatest rise in its A/A* outcomes, with a 13.1pp jump in the proportion of students achieving the top grades, followed by physical education (+11.1pp) and design and technology (+9.4pp).

At Grade A*, the greatest increase was in other modern languages (+19.2pp), followed by German (+11.2pp) and music (+10.5pp). The smallest rise was in other sciences (+0.8pp).

At GCSE, Spanish had the biggest rise in entries by percentage of any GCSE, with a 4.5 per cent increase to 108,982 entries, while geography saw the second largest. But German saw a 9.4 per cent decrease in entry levels to just 36,933 candidates.

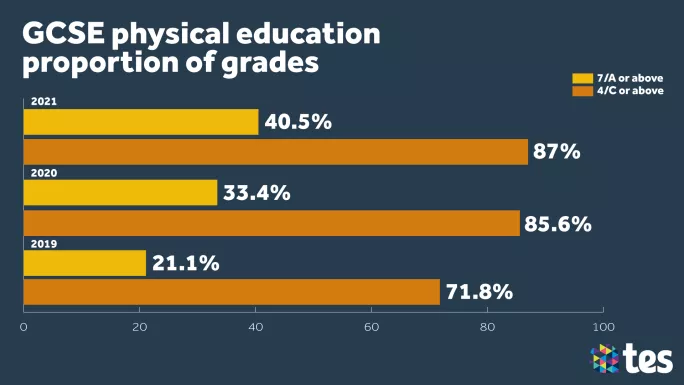

Results went up to the greatest extent in physical education at grade 7 or above, with a 7.1pp rise on 2020.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article