GCSEs: Concern over Year 11 absence as exams loom

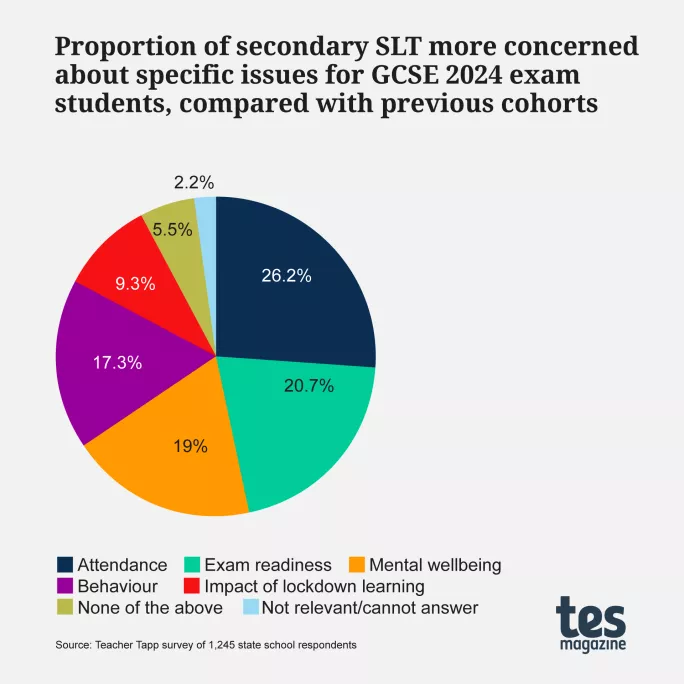

As GCSE exams approach, more than one in four senior leaders say they are more concerned about high absence among Year 11 students than last year, a poll shared exclusively with Tes has revealed.

The concerns about absence and the ongoing legacy of the pandemic have led to fears from some trust leaders that this year’s key stage 4 exams could lead to an even “wider divide” between the most disadvantaged and most affluent students.

More than a quarter (26 per cent) of secondary senior leaders surveyed by Teacher Tapp said they were more concerned about Year 11 absence than they were at this time last year.

And over one in five (21 per cent) senior leaders also said they were more concerned about Year 11 exam readiness this year than last.

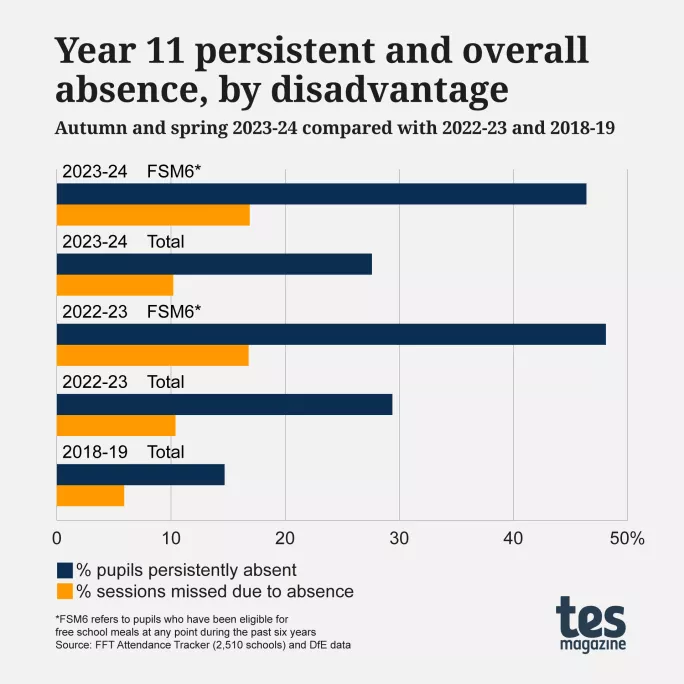

This comes as new data, seen by Tes, shows that Year 11 absence has remained nearly as high as the previous year and well above pre-pandemic levels despite a government drive to reduce it.

Year 11s have missed 10.2 per cent of half-day school sessions due to absence over the autumn and spring terms this academic year, FFT Education Datalab found, which is barely down from the 10.4 per cent recorded among GCSE students last year.

Wider divide in progress and outcomes

However, the proportion of disadvantaged exam students missing school has increased so far this year.

For those who have received free school meals in the past six years, the percentage of sessions missed due to absence increased to 16.9 per cent for this year, compared with 16.8 per cent last year.

- DfE: No Progress 8 replacement for next two years

- GCSEs 2024: Maths and science students get extra support

- GCSEs 2023: Grading fears amid high exam student absence

“We are seeing some legacy challenges with attendance that are particularly acute in our schools in more socially deprived areas,” East Midlands Education Trust CEO Rob McDonough told Tes.

“We think we’ll see a wider divide in terms of progress and outcomes,” he added.

Persistent absence rates among Year 11 students fell slightly to 27.6 per cent this year compared with 29.4 per cent in 2022-23, but are still well above the 14.7 per cent seen before the pandemic in 2018-19.

And nearly half of disadvantaged students (46.4 per cent) were persistently absent in the autumn and spring terms of this year, data shows.

Persistent absence has a big impact on student progress, said Vic Goddard, CEO of the Passmores Academy.

For the summer 2023 exams, the trust’s only secondary saw a difference equivalent to two grades in Progress 8 scores for students with 100 per cent attendance compared with those with 80 per cent.

Mr Goddard said the trust is starting to make improvements on attendance from last year, but it is taking longer to improve absence for the most disadvantaged students.

He added: “We are running into the same brick wall. We have this year’s worth of data on the impact of absence on attainment but we’re still in the same boat.

“I don’t feel like anyone in the country will be closing the disadvantage gap.”

Specific challenges for disadvantaged families

Dan Morrow, CEO of Dartmoor Multi Academy Trust, told Tes the trust has also seen absence rates improve slightly compared with last year, but not for the most disadvantaged students.

Mr Morrow added that government messaging on attendance without services and support is not enough, and does not account for “the specific challenges that faced disadvantaged families during Covid and more recently during the cost-of-living crisis, which has led to real stress and anxiety”.

He added: “Many disadvantaged Year 11 students also work and putting money into the house to keep it going is taking priority over potential gains of grades and outcomes.”

A recent report from the University of Bristol found schools are now running more food banks than charities as they increasingly step in as the fourth emergency service.

Both Mr Goddard and Mr Morrow said intervention to improve absence for future cohorts needs to be led with resources and funding to allow schools to decide how they can best make an impact in their communities.

National crisis in school absence

“I think we are experiencing a national crisis in school absence rates,” said Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at the University of Exeter.

He added: “There are many children in the classroom who aren’t engaging, but if they’re literally not at school that’s the worst-case scenario.

“It really worries me that young people going into the exam system this year are going to be unprepared. And that’s going to hit those children from under-resourced backgrounds hardest.”

Several sector leaders raised concerns about high Year 11 absence before GCSEs in 2023 as last year’s cohort was the first to take exams since Covid that were set to be marked using pre-pandemic grading boundaries.

Disadvantage gap

Last summer’s GCSE results saw the disadvantage gap reach its widest point since 2011.

Union leaders said the data showed more government effort was needed to support schools to tackle the impacts of the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis, which had reversed the narrowing of the trend seen in the years before 2019-20.

Academics at the University of Exeter, including Professor Elliot Major, warned last week that cohorts of children who saw disruption to their education from the pandemic could face poorer GCSE results well into the 2030s.

Professor Elliot Major said they predicted inequalities would widen in particular for the current Year 11 cohort in their GCSE grade projections.

‘Huge concerns’ over behaviour

Nearly a fifth (19 per cent) of senior leaders reported they were more concerned about Year 11 mental wellbeing than last year in the Teacher Tapp survey.

Additionally, 17 per cent said they were more concerned about behaviour for this year’s cohort than last year’s.

Current Year 11 students were in their first year of secondary school when the pandemic first hit and schools closed in 2020.

“They will have been a cohort that will have been particularly badly hurt,” said Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL).

Ms McCulloch said ASCL members have still been reporting “huge concerns” about attendance, behaviour, poverty and mental health.

The bigger picture

“It’s all interwoven,” she told Tes. “I think it’s right that we’re moving on now from making mitigations to exams - it needs to be about that much bigger picture of how we support kids at an earlier stage so they’re ready for exams, particularly kids from challenging backgrounds.”

Passmores Academy has been investing in family and home liaison workers to reach out to the families where absence rates are the highest, but these come with a cost.

“These young people lost fundamental years in their education and we’re still playing catch up,” said Mr Goddard.

“This cohort missed those first years of secondary school where you work out where you are and start to feel comfortable at school and that has a big impact.”

End of Covid recovery funding

Sutton Trust chief executive Nick Harrison said the absence crisis is likely to “exacerbate inequalities”, particularly with the disadvantage gap so wide, ”largely due to the impact of the pandemic and inadequate catch-up provision”.

Mr Harrison called for a national strategy to close the attainment gap, warning that “these inequalities will worsen without decisive action”.

This year, schools had access to the last tranche of a government subsidy aimed at supporting their efforts to provide catch-up interventions for learning lost during the pandemic through the National Tutoring Programme and the Recovery Premium.

Next year, schools will receive no catch-up support - though the Department for Education has said schools could continue to fund tutoring through the pupil premium.

Survey responses were drawn from 1,245 senior leaders at state secondary schools who responded to Teacher Tapp’s question on 14 April 2024.

FFT Education Datalab attendance data is drawn from 2,510 schools that take part in its Attendance Tracker.

A DfE spokesperson said the government is working to improve attendance and has seen 440,000 fewer persistently absent children compared with last year.

The spokesperson added that it has taken a range of steps to improve outcomes since the pandemic, including increasing pupil premium funding to £2.9 billion for 2024-25.

In a report published last week, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development said the government has put in place a “comprehensive strategy to fight school absences”.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article