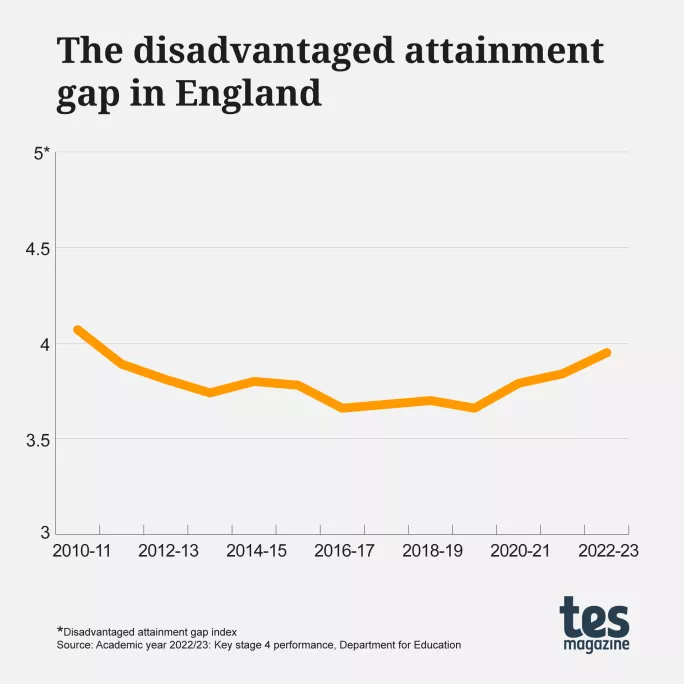

KS4 performance data: Disadvantage gap widest since 2011

The disadvantage gap is “heading squarely in the wrong direction” after reaching its widest point since 2011, leading to calls for urgent government intervention to help schools truly tackle the impact of poverty on educational outcomes.

New key stage 4 performance data, released by the Department for Education, shows the disadvantage gap index was 3.95 this year, up from 3.84 in 2021-22.

The last time the index was higher was in 2011, when it was 4.07.

‘Significant government intervention required’

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said it was clear from this data that “significant government intervention is required” to tackle the disadvantage gap, as the situation is worsening year on year.

“The events of the past few years, including the cost-of-living crisis and the pandemic, have clearly had an impact but in truth, very little progress was being made beforehand.

“We are now heading squarely in the wrong direction.”

He added: “There must also be greater urgency at a governmental level to address the shameful number of young people growing up in poverty.”

Carl Cullinane, director of research and policy at the Sutton Trust, added that the data was concerning and that progress made to close the gap over the past decade had been “eroded”.

The assistant general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, James Bowen, agreed that the data proved more must be done for schools but said support for other social services that support children in poverty must also improve.

He said: “This isn’t just about schools alone. Services like social care and mental health support have suffered from chronic underfunding over the past decade and this has an impact on students too.”

The effect of the disadvantage gap

The impact of the widening disadvantage was seen in other areas of the data too, with entry to the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) and attainment lower across every headline measure for disadvantaged students than other students.

For example, the disadvantage gap has widened for Attainment 8 compared with last year and with 2018-19.

In addition, the disadvantage gap for students achieving grades 5 or above in English and maths GCSE - 27.2 percentage points - is slightly narrower than in 2021-22, but wider than in 2018-19, when it was 25.2 percentage points.

A DfE spokesperson said: “We know the pandemic had a significant impact on education, which is why we have made £5 billion available since 2020 for education recovery initiatives, including 4 million tutoring course starts supporting pupils in all corners of the country.”

They added that almost half of the students receiving tutoring up until January 2023 were receiving free school meals.

English and maths attainment falls

The data also shows that the percentage of students achieving a grade 5 or above in both English and maths is 45 per cent, down on last year by 4.8 percentage points.

However, this is still above pre-pandemic levels: in 2018-19, 43.2 per cent of students achieved this, as did 43.3 per cent of students in 2017-18.

Meanwhile, the percentage of students achieving grade 4 or above in these subjects was 64.8 per cent this year. This is down from 68.8 per cent in 2021-22 but slightly up from 64.6 per cent in 2018-19.

This year’s exams marked the end of Ofqual’s “soft landing” approach to returning exams to normal following the disruption of Covid. In 2023, GCSEs fully returned to pre-pandemic grading, albeit with some protections built in.

More on GCSEs:

- How Progress 8 has impacted lower-attaining pupils

- Results 2023: Attainment gap widens after grading reset

- AQA plans for digital GCSE exams from 2026

Attainment 8 down but EBacc entries up

Furthermore, the average Attainment 8 score has also fallen to 46.2, the lowest it has been since at least 2015.

However, Dave Thomson at FFT Education Datalab explained that this year’s Attainment 8 scores are only really comparable with 2019’s (46.7 per cent).

This is owing to the different grading standards used during the pandemic, the 9-1 number grades being phased in during 2017-18 and the different attainment scores that were used prior to that.

Meanwhile, the percentage of students entering the EBacc has increased by 0.6 percentage points to 39.3 per cent. This is still far short of the government’s planned targets for EBacc take-up.

The North-South divide persists

Regional disparities in student attainment also remain.

The average Progress 8 score for students in the North East was -0.27, and -0.20 in the North West. At the other end of the spectrum, the average Progress 8 score for London was 0.27.

The percentage of students achieving grades 4 or above in English and maths GCSEs was 62.2 per cent in the North East, 62.1 per cent in the North West, 62.4 per cent in Yorkshire and the Humber and 61.8 per cent for the West Midlands.

In London, 71 per cent of students achieved a grade 4 and above in both these subjects.

League table caveat

This is also the first year that league tables have been released comparing schools on key stage 4 performance data since the pandemic.

However, the DfE has retained a caveat warning against making direct comparisons over time, stating: “School and college performance data for the 2022-23 academic year should be used with caution.

“In 2022-23, qualifications returned to pre-pandemic standards. Performance measures that are based on qualification results will reflect this, and cannot be directly compared with measures from 2021-22.

“There are ongoing impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, which affected individual schools, colleges and pupils differently.”

Confederation of School Trusts deputy chief executive Steve Rollett also cautioned against making like-for-like comparisons, saying “blunt comparisons may well be misleading”.

He added: “When viewing the performance of schools and trusts, it remains vital to remember that schools and communities have been differentially affected by Covid-19 and its aftermath, including an ongoing and significant attendance challenge in some areas.”

However, writing for Tes today, AET CEO Becks Boomer-Clark said she is concerned by the return of league tables and their merits for the system.

“I worry about the impact that combined pressures of public accountability are having on our front-line teachers and leaders - be that inspection outcomes or league tables,” she wrote.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article