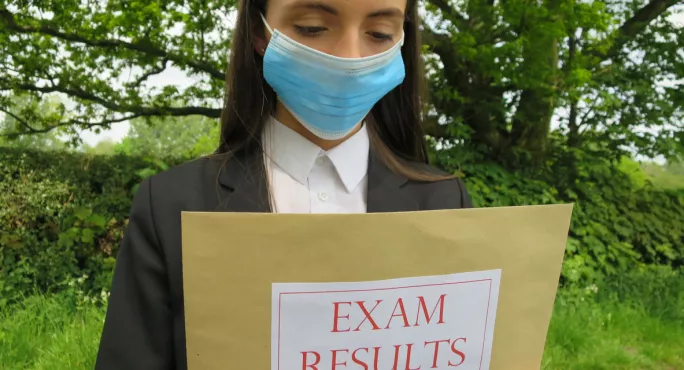

GCSEs 2021: How to give fair teacher-assessed grades

According to an old story, a traveller in Ireland stopped one of the locals as he passed through a village and asked for the best way to Dublin.

“If I wanted to get to Dublin, I wouldn’t start from here,” came the reply.

In some ways, this is where we find ourselves with assessment and grades in 2021. The failure to do any contingency after last summer’s shambles was astounding.

We didn’t wish to start from here, but here we are and we need to ensure that our students get fair grades, given all they have gone through.

Read more

-

GCSEs 2021: 10 unanswered questions about summer assessment

- Covid: The science of school closures

- Back to school: Can we close the attainment gap?

Some have welcomed teacher-assessed grades (TAGs), arguing that teachers know their students best and understand what their particular cohort has faced. There is some truth in this, particularly this year, but that risks negating some of the benefits provided by the examination system.

As a senior examiner, I am well aware that the examination system is not perfect and that we need to make it better, but it provides an anonymous and independent review of the candidates by a trained assessment professional. Each of these things matter.

In terms of anonymity, we know that TAGs may involve unconscious bias. It is also hard to take our knowledge of the student and their circumstances out of the equation. In terms of independence, this may vary by institution: is SLT breathing down teachers’ necks to improve results? Are there particularly forceful parents?

However, it is the benefit of trained assessment professionals that is worth focusing on. It is not always the case that teachers know best in terms of assessment. Time spent delivering training to teachers suggests that very good teachers can often have quite different understandings of “the standard”.

This is not teachers’ fault; most are crying out for more support and guidance on the level that they should be marking at and the grades to award. Exam boards could certainly be more transparent. The marking and the grades are different issues, and it is worth taking each in turn.

GCSEs 2021: How do teachers give the right marks?

When we talk about the need to get everyone marking to the same level, we are talking about what examiners call standardisation. It is easy to have our own favoured approach to how questions should be answered; part of standardisation is unlearning this and learning to look with an open mind at what is written.

As well as the content, examiners are also given a steer as to the standard on longer answers. Perhaps one question is particularly challenging and needs a little more generosity. For TAGs (particularly if we are using different questions), how can I be sure that your 15/20 on a question is roughly the same as mine?

Using the exam board training and exemplars when they arrive will be key (if you are a leader, it is vital that staff are given time to engage with this). Make sure you do some moderation with colleagues, and perhaps those in other institutions (particularly if there is an examiner in that institution).

The aim is that the marks we give are as in line as they can be under the circumstances. As I have said above, getting some anonymity and independence into the process may not be a bad thing.

How do teachers translate this to grades?

Examiners do not actually give the grades; they just give a mark. The awarding of grades is done afterwards by a combination of statistical analysis and senior examiner judgement.

It is worth conveying to students that this is not an exact science. If you look up the grade boundaries for your subject, they may show that 75/100 was needed for an A one year but 80/100 was needed the next. This shouldn’t be a surprise; no two papers will be exactly the same level of difficulty and no two cohorts are exactly the same.

So when we get to the stage of translating marks into grades:

- Look up the grade boundaries for the past two to three years..

- Think how your assessments compare with those with published boundaries. If we have given a shorter assessment with advance notice of the question or a longer time limit, then logic suggests that a higher mark would be needed for an A.

- Think about your cohort: how does that student who we think may be in A-grade territory compare with the A-grade student you remember from two to three years ago?

It is perhaps inevitable that there will be some grade inflation this year. It’s not that everyone is cheating; all that is needed for grade inflation is that each centre gives the benefit of the doubt in a couple of cases.

Is this necessarily wrong? If any cohort needs a break, it’s this one. They have coped with so much that is not their fault. Neither is it our fault; we didn’t wish to find ourselves here but our job now is to as fairly as possible award them the grades they deserve.

Chris Eyre is a senior examiner

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article