UK’s Pisa scores fall in maths, science and reading

Scores in maths, reading and science have fallen among the UK’s 15-year-olds taking part in a major international assessment.

Today, results have been released from the latest Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) survey, which is published every three years and compares education outcomes between high- and middle-income countries.

Scores fell in England, Scotland and the UK as a whole, although their international rankings have improved in maths and reading since the last survey in 2018.

- News: Spielman highlights drop in focus on science teaching

- Analysis: What do the 2022 Pisa rankings really tell us about the UK?

- Pisa tests 2022: The key insights behind the headlines

- Background: How did the UK perform in Pisa 2018?

- Explainer: Everything you need to know about Pisa tests and world rankings

The Pisa survey, compiled by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), focuses on students’ understanding of concepts rather than being linked to the school curriculum.

Today’s results are from tests taken in 2022 that involved 690,000 15-year-olds across 81 countries and economies.

Students spent an hour answering questions on maths, and another hour answering questions assessing their reading, science and creative thinking, although students in England did not participate in the latter test.

The latest results show that England has risen up in the rankings from 17th to 11th in maths, according to a separate University of Oxford research report published by the Department for Education.

And it now ranks 13th for both reading and science, having previously been placed at 14th and 13th respectively.

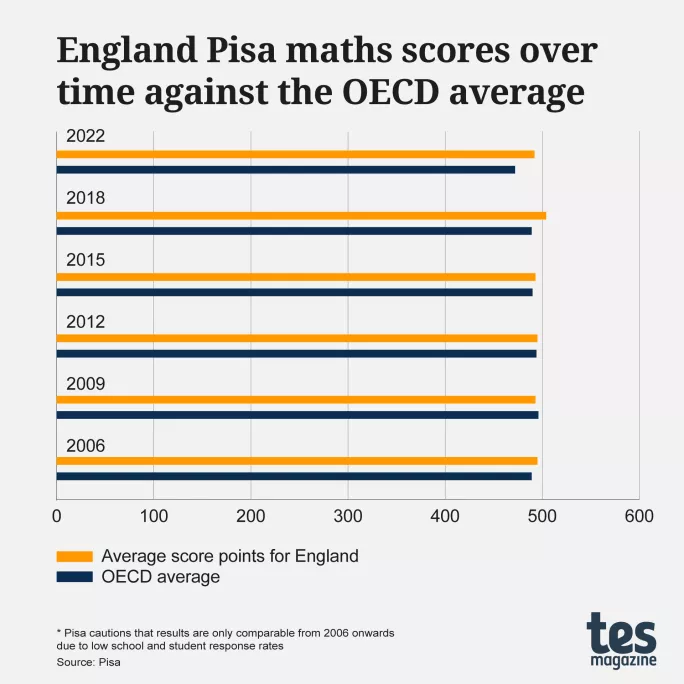

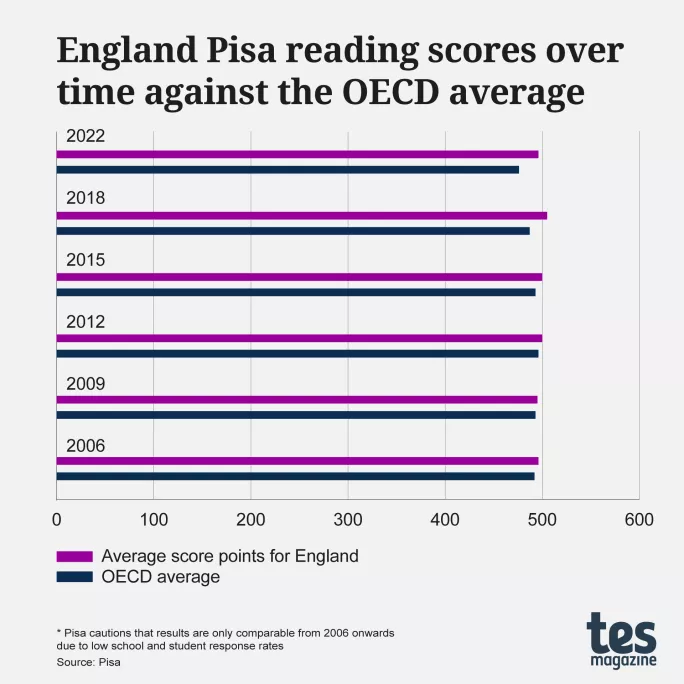

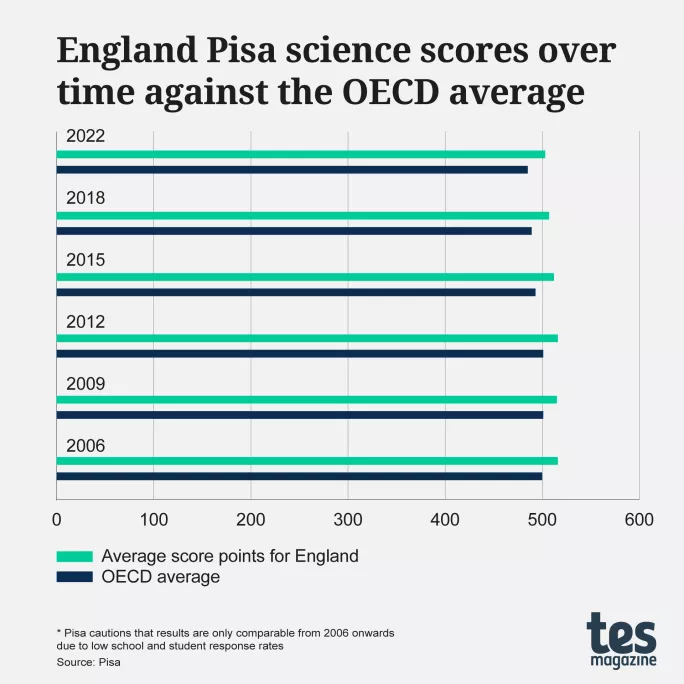

How did England score in maths, reading and science?

However, England’s average scores have fallen across the board.

The average maths score was 492, 12 points lower than in 2018:

And reading scores have fallen by nine points since 2018:

Meanwhile, scores for science are four points lower than in 2018:

Andreas Schleicher, director for education and skills at the OECD, said: “Those declines should concern us a lot.

“If you think of 20 points as broadly equivalent to a school year, you get a sense of the magnitude of this decline.

“I think, if you lose half a year or three-quarters of the year in outcomes, that is equivalent to the gains that we have seen in two decades in some countries.”

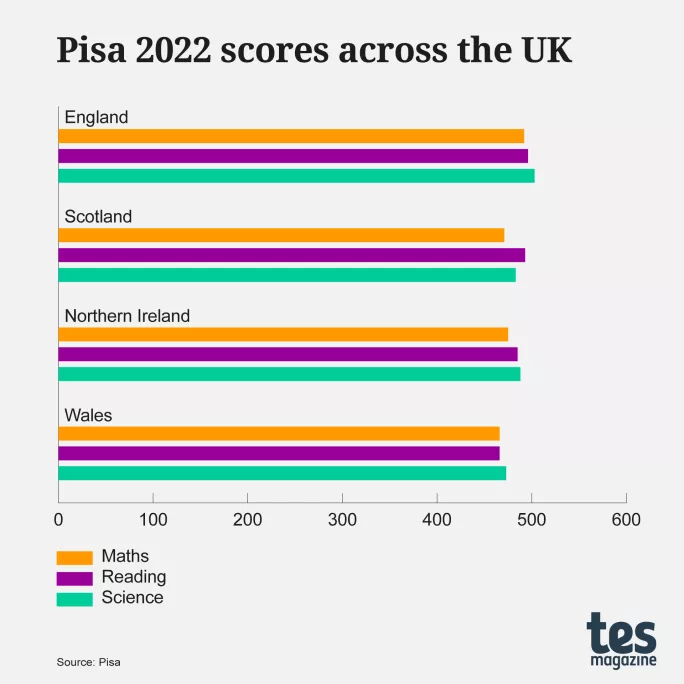

How did the rest of the UK perform?

Scores in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales have also fallen, with England performing slightly better than the other devolved nations. (You can find more details about the Scottish results here.)

UK-wide, the average scores were 489 in maths (13 points lower than in 2018), 494 in reading (10 points lower) and 500 in science (five points lower).

But UK rankings have also improved in two of the three subjects, rising from 18th to 12th in maths and from 14th to 13th in reading, with science staying in 14th place.

England and the UK as a whole remain above the OECD average in all three components.

Mr Schleicher said: “What is interesting is that we find for the UK there is a lot more performance variation within schools in the UK than between them.

“I say that because so much of UK policy focuses on school performance with the Ofsted rankings and how parents should choose the right schools, but looking at this data that’s not such a relevant question.”

UK participation rate target missed

Pisa’s methodology has attracted some criticism in the past, and the number of countries participating varies from year to year.

Some 12,972 15-year-olds in the UK completed Pisa in 2022 across 451 schools, but these participation rates fell below Pisa’s minimum target.

The UK’s scores may have been slightly lower with a better response rate, analyses found.

The latest results also need to be considered in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, experts say.

Some 63 per cent of students worldwide in Pisa 2022 reported that their school building was closed for more than three months owing to Covid.

And 39 per cent said they had trouble understanding their schoolwork at least once a week while remote learning.

In the UK, three in five students reported that they frequently had difficulty motivating themselves to do schoolwork while learning remotely - more than double the share of students in Guatemala, Iceland, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Moldova and Chinese Taipei.

Decline in scores ‘not just about Covid’

Natalie Perera, chief executive of the Education Policy Institute, said today’s Pisa results “confirm that England, alongside many other OECD nations, has experienced considerable learning loss as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic”.

The results also show the need for the government to prioritise education, teacher recruitment and improving children’s access to public health services and safe housing, she added.

Mr Schleicher wrote in this year’s report that the pandemic may seem an “obvious factor” in the decline in scores that some countries experienced - but was not purely to blame.

He wrote: “Educational trajectories were negative well before the pandemic hit. This indicates that long-term issues in education systems are also to blame for the drop in performance. It is not just about Covid.”

Many other countries have experienced a drop in their scores since 2018, particularly in Europe. The Netherlands’ scores, for example, fell by 27 points in maths, 26 points in reading and 15 points in science.

East Asian countries such as Singapore and China, however, have retained their top spots.

UK worse than average for wellbeing

The survey also included questions on wellbeing. A quarter (25 per cent) of UK students said they were not satisfied with their lives, higher than the OECD average of 18 per cent.

The UK also had a higher-than-average number of students reporting being bullied at least a few times a month: 27 per cent of girls and 28 per cent of boys, compared with OECD averages of 20 per cent of girls and 21 per cent of boys.

And 10.5 per cent of UK students reported experiencing food insecurity, slightly above the OECD average.

‘A starting point, not an end point’

Christian Bokhove, professor in mathematics education at the University of Southampton, warned against placing too much weight on today’s results.

He told Tes: “It is hard to compare [2022 and 2018] data given that there has been a pandemic in between, and [owing to] the sampling issues in the UK.

“All these countries differ in how they went about the pandemic and there are a lot of variables affecting these results.

“All international assessment data like this is a starting point for discussion, though people tend to use it as an end point.”

Overall, most of the UK scores were similar to pre-2018 levels, Professor Bokhove said, adding that 2018 scores were “an outlier for reading and maths”.

However, he warned: “We have been declining for a while in science. I do think that science as a subject has been undermined for quite some time and has been deemed less important, and some people have feared that may have an impact.”

Teacher shortages linked to performance

In about half of all countries and economies with comparable data, school principals were more likely than their 2018 counterparts to report a shortage of teaching staff.

Headteachers at more than half (54 per cent) of the schools attended by UK participants said teacher shortages hindered their capacity to teach, up from 28 per cent in 2018.

Nearly one in five (19 per cent) of UK students were at schools where heads reported teaching capacity was hindered by “inadequate or poorly qualified” teaching staff, up from 9 per cent in 2018.

Schools reporting teacher shortages tended to score lower in maths. Researchers said that the availability of teachers to help students in need has the strongest relationship to maths performance across the OECD, even compared with hindrances such as Covid school closure.

Disadvantage gap remains stable

The disadvantage gap in the UK’s Pisa scores has remained broadly stable over the past decade.

The gap between the highest-performing 10 per cent of students and the lowest-performing 10 per cent did not change significantly in maths and reading between 2018 and 2022, but widened in science.

In maths, the most advantaged 25 per cent of UK students outperformed the least advantaged by 86 points in 2022.

Commenting on today’s results, education secretary Gillian Keegan said: “These results are testament to our incredible teachers, the hard work of students and to the government’s unrelenting drive to raise school standards over the past 13 years.”

But Daniel Kebede, general secretary of the NEU teaching union, responded that “it takes a very opportunistic government to present the OECD’s depiction of a global crisis for education as a national success story”, pointing to the fact that scores are lower in all three subjects than in 2018.

And Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said Pisa “should not be used for cheap political point scoring, to justify a narrowing of the curriculum or to denigrate the work of schools in any UK jurisdiction”.

This was particularly true in the context of “severe funding pressures, teacher shortages, the uneven impact of the recent pandemic and the subsequent cost-of-living crisis”, he added.

The fall in maths scores comes amid plans set out by prime minister Rishi Sunak to require all children to study maths to the age of 18.

David Thomas, chief executive officer of Mathematics Education for Social Mobility and Excellence (MESME), said the Pisa results show “we’re still falling short of achieving our national potential” on the subject.

The former DfE adviser said children in England become top mathematicians at half the rate they do in countries like Singapore, and that we “should be doing much more to dig deeper into what seems to be preventing our talented maths pupils from becoming the mathematicians that we need for the economy of the future”.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article