Scotland’s Pisa scores drop across the board

Scotland’s scores in the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) 2022 report have fallen in each of its three categories: maths, science and reading.

This decline echoed a general and unprecedented fall in scores among the 81 countries and economies taking part.

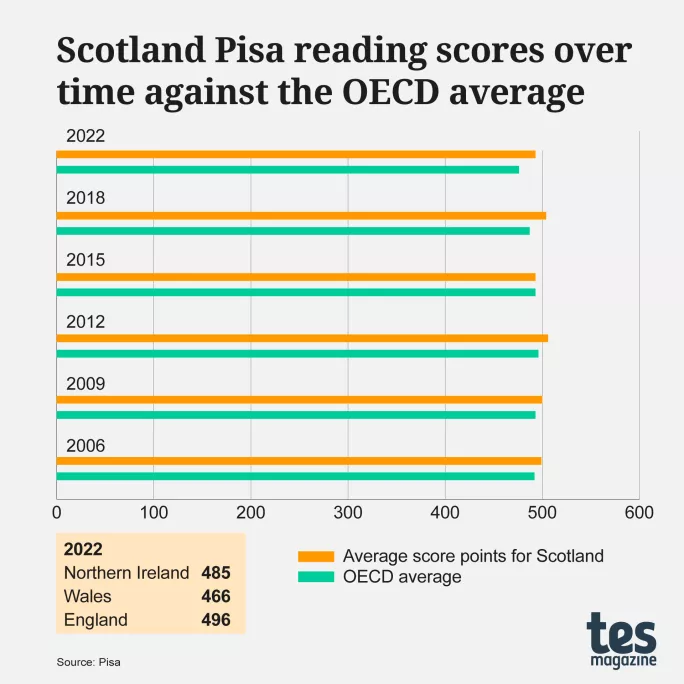

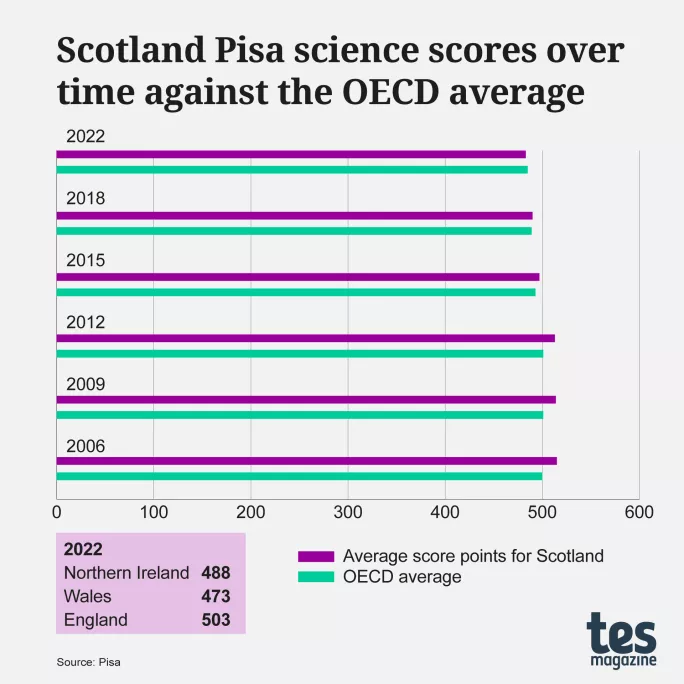

Scottish students scored close to average across the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for maths and science, and above the OECD average for reading.

The Pisa tests are a way of comparing the academic performance of students in different countries around the world. The 2022 report is based on results from 690,000 15-year-olds across 81 countries and economies.

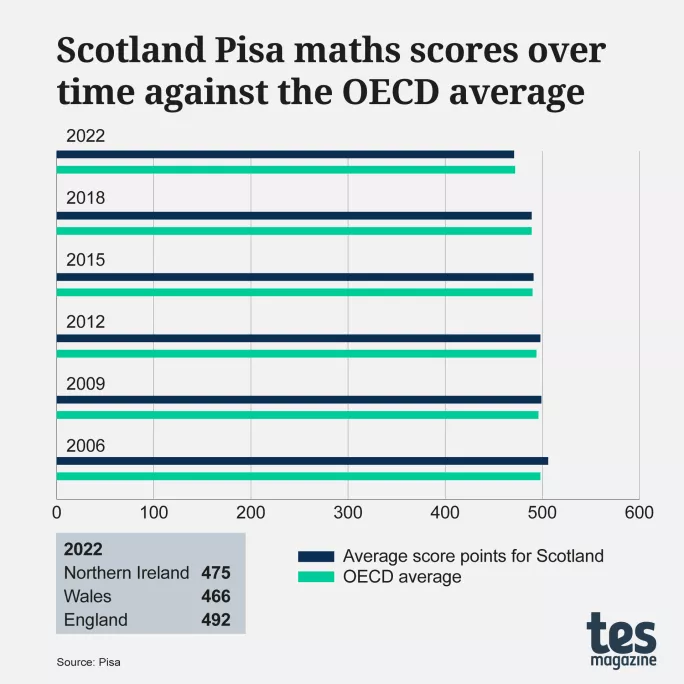

Maths sees biggest drop

However, today’s results represent the lowest or joint-lowest scores for each of the three categories since Scotland began participation in Pisa in 2000 (although it is advised that comparisons with some of the rounds of Pisa in the early part of the century should be treated with caution).

In Scotland, scores in maths - the main focus of Pisa this time - fell by 18 points (from 489 in 2018 to 471 in 2022); in reading they fell by 11 (from 504 to 493); and in science, they fell by seven (from 490 to 483).

According to the OECD, 20 points equates to a year of learning.

Pisa scores fell in all four parts of the UK: Wales saw the sharpest drop, the decline in England was least severe, while Scotland and Northern Ireland were in between.

In England, the maths score was 492, a drop of 12 points from 504 in 2018; it was 496 in reading (down nine from 505) and 503 in science (down four from 507).

Closing the “poverty-related attainment gap” is the defining aim of the Scottish government’s education policy. Yet, today’s report shows that the gap in mean maths scores between the richest and poorest students was wider in Scotland than in other parts of the UK.

In Scotland, socioeconomically advantaged students scored 98 points more in maths than disadvantaged peers (526 to 428). The average gap across OECD countries was 93 points. In England, it was 86 points, in Northern Ireland 81 and in Wales 76.

‘Not just about Covid’

OECD director for education and skills Andreas Schleicher said that generally declining performance internationally “should concern us a lot” - some countries had taken decades to accumulate the points lost between 2018 and 2022, and Scotland’s decline in maths over that period had been “a little bit steeper” than elsewhere.

He also highlighted that, since 2015, Scotland’s score in maths had dropped 21 points and concluded that Scotland’s performance had “not been so great” in maths in recent years.

Mr Schleicher warned against attributing falling Pisa scores solely to the Covid pandemic. In today’s report, he writes that the pandemic may seem an “obvious factor” in declining scores.

However, “long-term issues in education systems are also to blame for the drop in performance - it is not just about Covid”.

Speaking to journalists before the report’s publication, he said other issues that “policymakers should really take seriously” included: declining parental engagement; worsening teacher-student relationships; difficulties recruiting teachers; and the negative impact of smartphones’ use for leisure purposes.

Some countries had improved their Pisa performance, so falling scores were “not inevitable features of the pandemic”.

Mr Schleicher did not expect results to bounce back simply because the pandemic was over.

Context around scores

The publication of various Pisa reports today gives some idea of the context around each country’s scores, beyond the pandemic.

In Scotland in 2022, for example, 53.9 per cent of students were in schools where the headteacher reported that a lack of teaching staff had “hindered” the school’s capacity to provide instruction; the OECD average was 46.7 per cent.

When it came to support staff, again just over half of students in Scotland were in schools where the headteacher reported a lack of “assisting staff” was having a detrimental impact on learning and teaching (54.5 per cent); the OECD average was 37.2 per cent.

Lindsay Paterson, emeritus professor of education policy at the University of Edinburgh, today published an analysis in which he looks at Pisa scores since 2012, the first year of results since Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence was officially introduced in 2010.

He points to falls of 27 points in maths, 13 in reading and 30 points in science, and to the OECD advice that a 20-point change equates to around a year’s worth of learning.

“The Scottish decline associated with the implementation of Curriculum for Excellence has thus been equal to about 16 months loss of schooling in mathematics, eight months in reading and 18 months in science,” says Professor Paterson.

Parliament to debate Pisa

The Scottish government said that today’s Pisa report showed Scotland’s reading performance above the OECD average and higher than 24 other countries, and that Scotland was “similar to the OECD average” for maths and science.

Education secretary Jenny Gilruth said: “As is well understood, the Covid-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on our young people and their experience of learning and teaching.

“Pisa demonstrates this impact across the majority of countries participating. While every country in the UK has seen a reduction in its Pisa scores across maths and reading between 2018 and 2022, there will be key learning for the Scottish government and [local authorities’ body] Cosla to address jointly in responding.”

She added: “Since Pisa was conducted, wider evidence from both the 2023 national qualification results and the most recent literacy and numeracy data for primary show clear evidence of an ongoing recovery, which we are determined to build on.”

Ms Gilruth said she would address the Scottish Parliament with a “full update next week, reflecting on both Pisa and the 2023 national literacy and numeracy data, which is based on teacher judgement”.

- In the rest of the UK: Pisa 2022 scores drop in maths, science and reading

- Long read: How timetabling gets missed in education - and why it matters

- Big issue: Could banning mobiles ease Scottish schools’ behaviour woes?

- Pupil absence: How to improve school attendance in Scotland

- Staffing: Every secondary hit by teacher shortage, says education director

Andrea Bradley, general secretary of the EIS teaching union, said that Pisa test data was “limited in what it can say about the quality of learning within any education system, telling only a fraction of the story” but reflected “the most challenging of circumstances in the wake of the pandemic and continuing social inequality”.

Scottish schools and teachers are “swimming against a tide of cuts, which threatens now to be a tidal wave”, she said.

Ms Bradley added: “We know that Scotland has among the largest average class size and highest teacher class-contact time commitments of countries within the OECD, and those are nettles that the Scottish government will have to grasp if they are serious about delivering a better educational experience for Scotland’s young people, particularly in the wake of Covid disruption and the ongoing damage done by poverty and inequality.”

Pisa testing

The latest round of Pisa testing - involving nearly 700,000 students from 81 countries and economies - took place in 2022. Today’s report was delayed by a year as a result of the pandemic.

Across the OECD, compared to the previous Pisa report in 2019 (based on 2018 testing), performance fell by 10 points in reading and by almost 15 points in maths. Changes over consecutive Pisa assessments had never previously exceeded five points in reading and four in maths.

Pisa is the main source of data used by commentators to gauge the performance of Scottish school students internationally. Scotland withdrew from two other surveys - Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss) and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Pirls) - more than a decade ago.

However, in April, a few weeks after he became first minister, Humza Yousaf announced that Scotland would be rejoining Timms and Pirls.

Global competence

In 2020, Scottish pupils were among the top performers in a new and different kind of Pisa test looking at “global competence”.

They were among the most likely in the developed world to understand and appreciate the perspective of others, demonstrate positive attitudes towards immigrants, and score highly on a test that assesses the ability to evaluate information and analyse multiple perspectives.

Scotland was the only part of the UK to take part in this test. In 2018, the OECD indicated that England declined to take part partly because of a fear it would score poorly.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article