- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- GCSE maths: the power of productive struggle

GCSE maths: the power of productive struggle

Something I have learned from spending much of my working life in mathematics education research is that for every answer that you reach, you generate many more questions.

Our recent research into GCSE resit teaching and learning is a good example of this. A randomised controlled trial provided evidence that our intervention programme led to improvements in students’ exam scores. And, intriguingly, it was most effective for learners from the most disadvantaged backgrounds.

In fact, it led to these students effectively having a gain in exam marks equivalent to two extra months of learning.

An obvious follow-up question is: why is the programme most effective for these learners?

We have spent some time considering the issue and I conclude that the answer lies in the fact that we deliberately designed for students to struggle. Productively. And collaboratively.

Struggle: the key to maths success?

GCSE resit students may very well have spent years struggling with mathematics, but unfortunately, they have not been productive in terms of coming to an understanding of what are quite often basic concepts (the fundamental structure of number, proportionality, basic ideas of geometry, and so on). Our intention, then, is to reorientate students’ struggle in a way that productively leads to understanding.

Many educators - including Dewey, Piaget and Polya - have highlighted the importance of struggle in the learning process. But this is alien to what is often the approach in GCSE resit classrooms: reteaching most, if not all, of the curriculum, via direct instruction, at speed and with students revisiting topics and the teacher trying to clarify the rules and procedures that are necessary to answer GCSE questions.

Our alternative approach is to change students’ experiences of engagement with mathematics to one that asks them to work on the lesson with one of their classmates and with the teacher playing a facilitative/supportive - and much reduced - role. This requires substantial change in both students’ and teachers’ classroom roles and behaviours. We achieve this by the use of carefully designed classroom tasks and teachers working with colleagues to explore how they might achieve a change in their teaching approach.

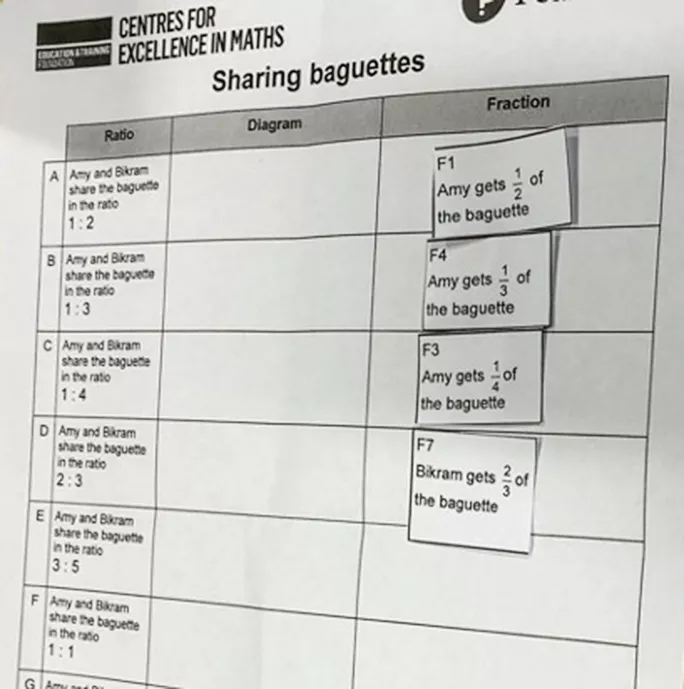

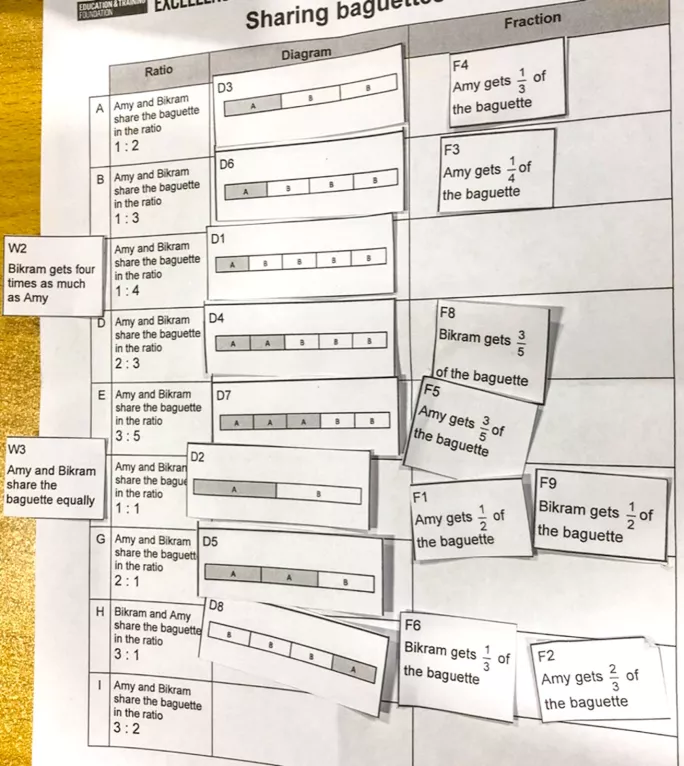

Let me illustrate. In one of our lessons, students explore fractions and ratios by considering how two people might share a baguette in various ratios such as 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 2:3, 3:5 and so on. They are asked to match fractions to these ratios by placing fraction cards on a template

It may be surprising to the teacher to find the prevalence of the misconception that the fraction ½ matches the ratio 1:2 rather than the correct fraction 1/3 - in our experience in resit classrooms, this can be above 75 per cent of students.

Because of the careful selection of ratios and fraction cards in the design of the task, students quickly get to a point where they can no longer proceed with their card matching. At that point, the teacher can supply the students with some diagram cards that they use to assist them resolve their difficulties.

As students collaboratively resolve their difficulties, the teacher takes a back seat, monitoring progress and minimally supporting them by asking questions that support their struggle in ways that allow them to be productive.

To achieve the improved learning outcomes that we did, we also systematically supported teachers to explore their own practice in collaborative lesson research groups based on Japanese lesson study principles. This allows teachers to learn from each other what, for many, is a substantial change in their practice, often leading to their own struggles.

I have found that the term “productive struggle” is much more likely to be used by teachers in schools in the US, where our work with Alan Schoenfeld’s team at the University of California, Berkeley resulted in the 100 Formative Assessment lessons that were found to have a large impact across the K-12 curriculum.

The next step in our work is an Education Endowment Foundation-funded Mastering Maths research study. This involves a large-scale randomised effectiveness trial that investigates if, when done at scale, and at distance from our team, the programme can replicate, or better, the impact of our earlier work.

Geoff Wake is a professor of mathematics education, based in the Observatory for Mathematical Education at the University of Nottingham. He leads the Mastering Maths research study.

If you work with substantial numbers of GCSE resit students in colleges in England and want to take part in the research, visit www.masteringmaths.org/

For the latest research, pedagogy and practical classroom advice delivered directly to your inbox every week, sign up to our Teaching Essentials newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article