- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How robots and pupils could interact in the classroom

How robots and pupils could interact in the classroom

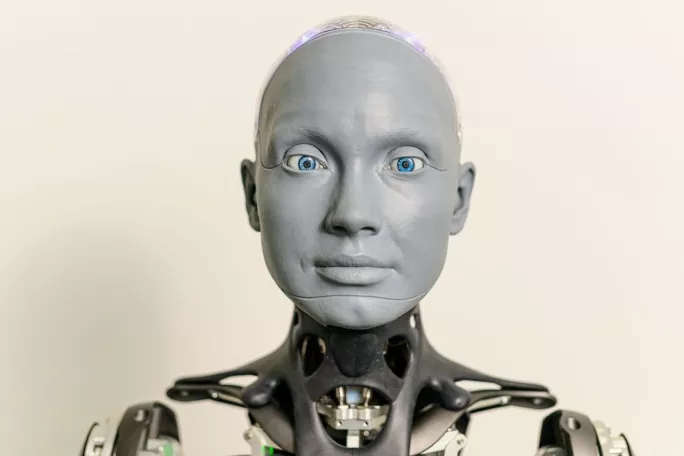

Last month we welcomed students from Lasswade Primary School and Lasswade High School, in Midlothian, to the National Robotarium here at Heriot-Watt University, so that they could meet Ameca, one of the world’s most advanced humanoid robots.

As robots become more commonplace in classrooms and other child-focused environments, understanding how children form trusting relationships with these machines will be crucial. With this insight, we can design robots to more effectively collaborate with teachers and help to educate children.

We’ve done considerable research on human-robot interaction. One of our studies found that a robot’s ability to perform its intended function reliably is the most significant predictor of whether humans will trust it. In other words, if a robot consistently completes its tasks as expected, humans are more likely to have confidence in the machine.

Children ‘trust robots more than humans’

A similar but separate study by scientists in Sweden, Germany and Australia shed some light on how children, in particular, perceive and trust robots compared to humans. The research revealed that children tend to trust robots more than humans, believing that when the humans in the study made mistakes, they were doing so on purpose, while the robots were not seen as making intentional errors.

So, why is trust between humans and robots so important? Putting robots’ potential applications in education aside, it is increasingly likely that they will become ubiquitous in the workplaces of the future. If we can get our young people comfortable living and working with them early, it will make that transition much easier.

- Analysis: Can a curriculum support coherence without removing teacher autonomy?

- News: UNCRC introduction is “historic day”, says commissioner

- Reform: Making Scotland’s Centre for Teaching Excellence an engine for improvement

This is why we invested in Ameca (pictured below). We want to use it to engage with people of all ages to try to demystify robotics, to break down the barriers often associated with the apprehension of interacting with a machine that looks a lot like you.

Ameca’s maker, Engineered Arts, designed it so that it mimics human behaviour as realistically as possible, maintaining eye contact and using familiar facial expressions and hand gestures, which are part of how humans interact with each other.

The students from Midlothian who visited in June were clearly awestruck by Ameca. Their eyes lit up when they walked through the door and saw it for the first time, some grinning from ear to ear. One little girl’s mouth dropped open and another pupil mouthed a silent “wow”. They were initially unsure about how to interact with Ameca but after a little prompting the questions started to flow.

What pupils like to ask robots

“Would you like to be human?” “Can you feel emotions?” “What is 1,000 plus 1,000?”. Even, “Ameca, do you like Taylor Swift?” (Turns out it does, or at least “can appreciate the emotional depth of her music”.)

The children then drew pictures for Ameca to identify. Most were of simple things like apples or a spaceship, which it was easily able to recognise. Impressively, it was also able to identify that one child had drawn more irregular pentagons than regular pentagons on their page.

Ameca’s blatant cheating at the game rock, paper, scissors, however - making its choice after the child it was playing had revealed his - wasn’t so impressive.

By the end of the visit, the children were posing for selfies with Ameca and a bond had clearly been formed. One little boy returned to the room after a break, ran up to Ameca with his arms outstretched and shouted, “Ameca, it’s me. I’m back!”

The limitations of robots

Ameca has limitations. It hasn’t been created to walk, for example, and does lose focus if too many people speak at once, so it won’t necessarily be the robot that we find moving among us in the years to come. But there is a higher purpose.

Research with school-aged children shows that puppets, like a favourite doll or teddy bear, can encourage learning and improve communication and behaviour. Talking to a puppet, as opposed to a person, makes the conversation feel less personal and more pretend. It is a play-based technique sometimes used in therapy to help the child feel less self-conscious and open up.

We believe it’s the same with robots. In terms of interacting with artificial intelligence (AI), for example, Ameca allows children to explore systems in a natural conversational manner, rather than battering questions into something like ChatGPT.

I think the questions that the children were asking showed their curiosity and interest in robotics and AI. That they so quickly adapted to Ameca was interesting - they were talking to it as if it was something more than a robot, as if it had a human personality. And that’s a good sign.

Michelle McLeod is industry and schools engagement lead at The National Robotarium at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh

For the latest Scottish education news, analysis and features delivered directly to your inbox, sign up to Tes magazine’s The Week in Scotland newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles