- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Reading ages: what does the research say?

Reading ages: what does the research say?

Imagine three 14-year-olds. All are in the same class at school, but have very different reading ages: one has a reading age of 6, the second 10 and the third 16.

What does this mean?

Well, one obvious implication would be that the first student is eight years behind, the second four years behind, and the third two years ahead. But what is a teacher to do with that information?

Does it mean the first two students need additional support? What kind of support? And is the third an exceptionally good reader?

Recently, I’ve been spending a lot of time working with secondary schools, and thinking about reading ages.

Finding that a child or adolescent is behind age expectations can be alarming for teachers and parents, and distressing for the young person. It can also lead to expectations that additional support or resources should be directed towards that student.

It absolutely goes without saying that we want to ensure that all students have the reading support that they need.

However, reading ages should not be used to make those decisions, because they are deeply misleading.

Reading ages: how do they work?

The problem is that while reading ages seem straightforward, they actually tell us less than it might seem. This is because there isn’t one six-year-old way of reading, or a 10-year-old way of reading, and so on. Instead, students vary in how they read, just as they do in height and weight, and adolescents, in particular, vary a lot in their reading abilities.

- Primary: Why the KS1 results show we’ve put policy before pupils

- Teaching: Should you keep the same class for more than a year?

- Education research: Why you can’t (completely) trust the research

In fact, my research has shown that reading at the level of an average 10-year-old is within the expected range of abilities for a 14-year-old. So, our student who is “reading four years behind” is actually reading within the average range for their age.

The research also shows, though, that reading at the level of a six-year-old is extremely unusual for a 14-year-old. So, this student raises a clear cause for concern and presents a case for additional resources and support. However, the reading age alone doesn’t tell us whether a student has a reading need.

So, what is the solution to the reading ages issue?

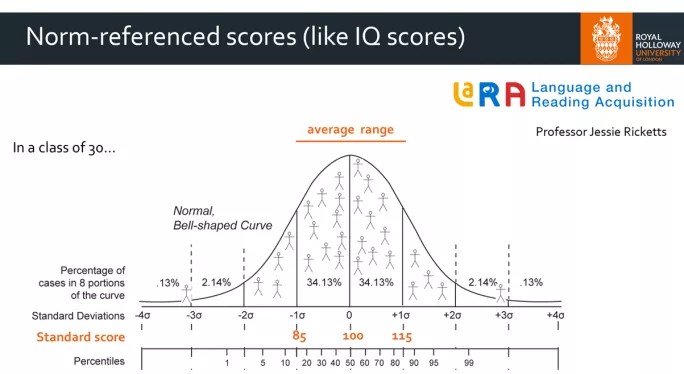

My approach over the past decade or so has been to work closely with teachers to understand how they might use diagnostic assessments to inform their decision making around reading support. Part of this has been to explain the normal curve and present norm-referenced scores as an alternative to reading ages.

Norm-referenced scores tell you where a student is in relation to peers of the same age. For our students here, they would show us that the second and third are within the average range for their age, but the first is substantially below the average range.

Some teachers and school leaders have told me that this approach is useful. However, I got the sense that it wasn’t helpful for everyone. So, in thinking about how to do better, I organised a workshop with teachers.

Two things emerged from this. Teachers told me that understanding the normal curve and what it means for assessment is challenging but that my diagram with children superimposed on it helped. This is the slide that they were referring to:

They said that knowing that there will be about five children who are below the average range in the average class helped. Of course, this number assumes that the children in the class are representative of the population, but this may not be the case. For example, I have been working with schools in Blackpool where the distribution looks very different and classes may well have many more than five children below the average range.

The other point that came up was that schools might find some kind of traffic lights system useful to indicate general reading level - although some teachers were concerned about associating children with the colour red. Rather than colours, then, an alternative might be something like “at the average range”, “below the average range”, or “above the average range”. Indeed, commercial diagnostic assessments often come with reports that signpost strengths and weaknesses using similar categorical systems.

So, where does all of this leave us? Well, it doesn’t suggest that a radically different way of explaining reading ages and their alternatives is needed.

Instead, the normal curve should be explicitly linked to children in the classroom and this can be supplemented with a categorical system that acknowledges the expected range of reading ability at any age.

Professor Jessie Ricketts is director of the Language and Reading Acquisition lab at Royal Holloway, University of London

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article