- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- The real cost of classroom interruptions

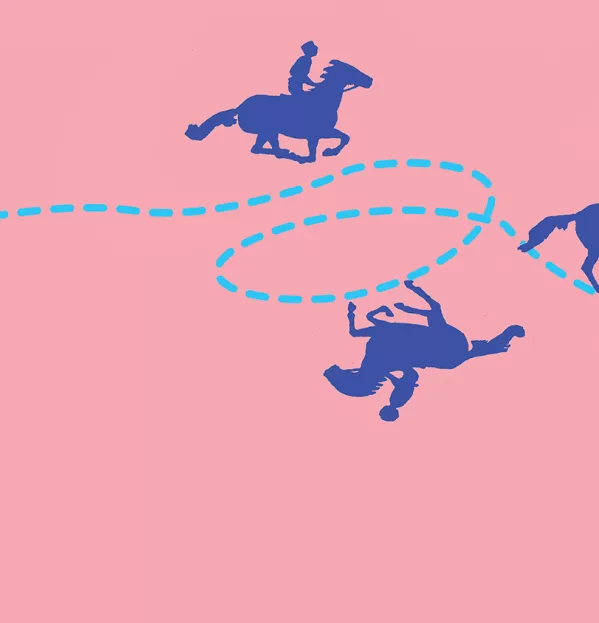

The real cost of classroom interruptions

Lessons are punctuated with constant interruptions. A child might turn up 10 minutes late because they’ve been to the dentist; a fire alarm test might be held midway through class; a supply teacher might knock on the door, asking for help with the tech in the neighbouring classroom.

Many of these interruptions sound like trivial things and, in their own way, they are. However, these little interruptions create a significant problem.

Quite how significant that problem is might surprise you. Matthew Kraft - a former high school humanities teacher in the US, who is now associate professor of education and economics at Brown University - undertook research into the impact that “external” interruptions have on lessons. Earlier this year, he published his findings in a paper titled The Big Problem With Little Interruptions to Classroom Learning.

Kraft calculated that interruptions can add up to between 10 and 20 days of lost instructional time over an academic year, and he suspects that they are having a detrimental impact on children’s ability to learn.

Tes caught up with Kraft to find out why these little interruptions are potentially making such a big dent in pupils’ progress and how school leaders can help to reduce them.

Tes: How much existing research was there about this subject?

Matthew Kraft: A lot of teachers have written blog [posts] and op-eds about their frustration with being interrupted but there was no broad-scale, quantitative evidence that would help us to understand how much this really was a feature of the classroom environment.

Some really pioneering work had been done by a few scholars as early as the 1950s in the US, which saw some teachers keep journals and log all the times that their classroom was interrupted. This afforded some eye-catching commentaries about how these types of interruptions undercut class momentum and could wreck the instructional efforts of teachers and the learning of students.

So, there was certainly good anecdotal evidence and a lot of work by sociologists, saying: “Hey, this is just part of the normal school day culture”. But in terms of trying to understand its consequences - in terms of what happens when you try to add it all up - we knew very little, and so that’s what I set out to try to answer.

In your study, how did you go about trying to calculate the impact that interruptions were having on teachers and pupils?

I’m a professor at Brown University, which is located in Providence, Rhode Island, and I was fortunate enough to have developed a relationship with the Providence public school district, who were, at the time of the study, engaged in an effort to maximise student learning. And to maximise student learning, they were focused on the use of time during the school day.

So, I was having conversations with them about this and I said: “Hey, part of the picture is likely to be these interruptions. Can we work together to systematically track this?”

We set out to capture that in a two-pronged approach. One was to just have a team of researchers sitting inside classrooms across schools in the district, observing, recording and logging the number of external interruptions that happen. Our second approach was to administer a survey to students, teachers and administrators, which was something the district was already doing, so we got to add a couple of questions about their experiences [in relation to interruptions]. It gave us really large-scale data - more than 13,000 students responded and more than 1,000 teachers - so we had two rich streams of new data on this issue.

How easy was it to define what constitutes an interruption? What definition did you use during the study?

We went about understanding how to categorise and judge what an interruption is in a really iterative way. We did a couple of pilot observations, just to see what was happening, and what we decided was that we were going to focus on external interruptions - things that are arguably outside of the control of a teacher, so they originate from somewhere outside of the classroom and intrude into the classroom.

We didn’t record if a student was being disruptive, distracting their classmates or using their cell phone, or any of the other things that happen in classrooms on a semi-regular basis. That wasn’t the issue we were looking at.

We were looking at things like intercom announcements; a call to the phone, computer or radio in the teacher’s classroom making some kind of request; and what we call a “drive-by” visit by another teacher or school staff member.

One of the interruptions that we didn’t initially have on our radar, but which we became very aware of while we were observing, was students who would arrive to class late. That slow trickle of students into the classroom after instruction had begun was one of the main contributions to these external interruptions because, as you might imagine, it caused the teacher to have to pause and re-orientate that new student, and that student might also distract other people as they entered the classroom.

What did you discover in terms of the impact these external interruptions were having?

The bottom line was that both our survey data and our observational data pointed to an extreme amount of instructional time lost due to interruptions and the disruptions they cause - somewhere between 10 to 20 school days [a year].

In the US, if you’re absent for approximately 10 per cent of the school year, you are considered chronically absent or truant, and in violation of school attendance laws. And so, by that definition, in many of the schools that we observed, every student in the building could be considered truant or chronically absent simply by showing up every day and having their instruction interrupted.

Did you also record the impact of internal interruptions caused by external interruptions?

We did. Our team members have stopwatches with them in the classrooms and they would start timing when an external interruption occurred. They would mark the time when that external interruption ended but continue timing until the class was able to get back on track and engaged in the lesson.

So, we have very precise accounting estimates of that lost time and that’s how you end up with an estimate of 10 to 20 days. And I think that’s actually an underestimate because what we can’t observe is when a student is quietly looking at their work but they’re not able to mentally catch up and engage with where they were - there’s just a lag or a delay. There’s a lot of evidence from psychology literature showing that this type of small interruption can lead to task delay, especially when you’re engaged in more cognitively demanding tasks.

You said that students arriving late for class was a common theme across schools in the district. Were there any other sort of commonalities in terms of the types of interruptions or when they occurred?

We looked at this very closely as well and we found that the beginning of the school day was a peak time for interruptions because it combined a common policy to have intercom announcements in that first period as well as a lot of students arriving late for class. So that combination really heightened the amount of interruptions.

But what we did see is that interruptions occurred throughout the class period, so it wasn’t like they were exclusively occurring at the beginning. We also saw another spike at the end of the day, when schools would often schedule intercom announcements and [teachers] might also be trying to catch up with a kid for some thing that they need to do, like a [catch-up] test or handing in a permission slip at the end of the day.

The other thing I’ll add is that, in some classrooms, we observed the pattern where students and their teachers would systematically delay the start of the class until the intercom announcements were done, but they didn’t start immediately because these intercoms were scheduled five minutes into the class or five minutes before the end of the period. So students would start packing up and putting their books away even though there was five minutes or more left of class, and so it led to this systematic shortening of the school day.

In terms of your findings, do you think interruptions create the same amount of damage across the US and in places like the UK and Europe?

The interruptions we observed are probably more acute and more frequent in the district we studied than they are in many other contexts. But even if, let’s say, half as many interruptions might happen in a typical district, that’s five to 10 instructional days - and what I want to emphasise is that these are interruptions that I think the school has considerable agency to minimise.

What impact do you think these interruptions have on teachers and their ability to teach?

We didn’t set out to study teachers’ experiences with interruptions - we were aiming to quantify their frequency, nature and lost instructional time. But in informal conversations with teachers, we consistently heard that these interruptions really frustrated them. It made them feel as if their efforts to teach kids were not really appreciated or valued; that they could be interrupted at a whim for what, in some instances, were very trivial things. I think it really weighed on teachers in that way.

We also heard about how it was frustrating because it disrupted lesson momentum. So you’ve got the kids on board, you’ve explained the instructions, things are running smoothly then, all of a sudden, that momentum is disrupted and teachers - in many cases - had to go back and re-explain the lesson. That was harmful in terms of the students’ progress but also in terms of teacher morale.

What about the detrimental longer-term impact that these interruptions have on learning?

We don’t have definitive evidence on what the causal effects of these interruptions are on learning in the field in schools. There’s a really compelling body of research, from lab experiments done by psychologists, estimating the impact of frequent interruptions on different tasks and they find that overall accuracy of task completion and quantity of tasks completed degrades with the increased amount of interruption. So there’s some very credible evidence to suggest that this might really matter for students’ learning overall.

What I will say is that when you just look descriptively at the schools in the district we studied, there was a range of overall achievement across the schools and there was a strong association between schools that had more frequent interruptions and lower overall achievement.

Now, interruptions are not the only thing that is going to be a potential driver of that relationship. Schools with more interruptions had more kids who were showing up late. But what was really striking is there wasn’t a single school we observed that was high achieving and also had high amounts of interruptions. It’s not a profile that we saw in the data, which suggests that it’s not a school environmental culture and climate that builds the opportunity for high achievement.

Given the cumulative impact that these little interruptions are potentially having on children’s progress, why do you think it’s an area that’s been overlooked so far?

I think psychologists have a couple of insights to this. One is that humans are just really bad at adding up a whole bunch of frequent, small events. We just generally misperceive how much all these things add up to over time.

Schools go for 180 days [per year] in the US, which is a long time, and it’s hard not to sit there and be like, “oh, that was just five seconds, 10 seconds, a minute - it’s no big deal”. But day in and day out, that adds up.

[Another insight is that] we actually found very strong evidence that principals, school leaders and administrators systematically underestimated the frequency of these types of external interruptions compared with students and teachers.

I know you believe that this problem is something we can easily tackle, so what can be done to minimise interruptions?

Every school should engage in an effort to track the frequency of interruptions for a week. They should ask teachers to keep a journal and find out what the primary [culprits] are in their school, because they will differ and so the solutions will differ.

But it is really about establishing school norms and about holding instructional time as sacred. So you don’t pull a kid out of class for something that can wait until the end of the school day. Or you don’t interrupt someone to ask for some materials - you wait till a lunch break or a passing period. That would embolden teachers to basically say: “No interruptions. I’m putting a sign on my door, saying: ‘Do not interrupt the important lesson that we’re engaged in’.”

Another thing to implement is a clear system in classrooms for what students do when they show up late, which is very important. Have a system whereby there’s a place where the activity and the materials are always located, and [ensure] that students know they can just go and grab them when they turn up late. Or maybe there’s a student representative whose job it is to welcome a student who comes in late and orientate them to the class rather than a teacher stopping what they’re doing? Those types of norms and expectations can minimise the disruption.

Your research shows how disruptive interruptions can be. Are all interruptions bad? What about teacher observations?

There is definitely a good reason to show up in a classroom unannounced. I spend a lot of my time studying teacher observation and feedback - teacher coaching - and we want schools where there’s a culture of open doors for colleagues who observe each other, and for supervisors, administrators and instructional experts to come in and give feedback to teachers about what they observed.

But that wasn’t what I saw going on in any of the interruptions that we tracked. We want students to be acclimatised to people coming in and out [of a classroom], but I don’t think that is the real culprit of what’s driving these negative external interruptions. So, we need to find a way to promote that in a non-disruptive way while minimising the things that are particularly problematic because they cause students to become distracted and [go] off task.

Given how much learning children have missed owing to the pandemic, how important do you think the findings of your research are?

The research has rung true for many schools and, in a moment where we have to value every single minute we have with students to support them in the wake of this global pandemic - and maximise the learning time we have - I think interventions and efforts and policy approaches to minimise interruptions are more important now than ever.

However, I found that schools are really overwhelmed right now with just the basics of serving students and meeting their needs and operating safely, and so it’s hard to get their attention on something that - even despite the research that I’ve done - still has a perception of “well, that’s just kind of an annoyance; it’s not a real problem”.

The potential here is that there is real time we could recover with better organisational practices in schools to minimise interruptions. What I want to emphasise is that, compared with other approaches - like extending the school day, or summer school, or programmes during winter and other vacations - this is a much more affordable and feasible way to increase instructional time.

It is potentially low-hanging fruit that we have to recognise and take advantage of.

Matthew Kraft is associate professor of education and economics at Brown University. He was speaking to freelance journalist Simon Creasey

This article originally appeared in the 15 October 2021 issue under the headline “Do not disturb”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article