- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- ‘A school isn’t a building - it’s a shared culture’

‘A school isn’t a building - it’s a shared culture’

The notion of “school” is something everyone understands. No one ever asks me what I do as a teacher, because they went to school and had teachers themselves. We all therefore know (or think we know) what schools look, smell and sound like. Our children go to school, too, and so we experience all over again our understanding of the “schoolness” of schools.

But, for what have become very obvious reasons - over a much longer time than any of us would have wished for - we have all had to reassess our idea of “school”. School has become the kitchen table, the spare room, the makeshift desk in the shared bedroom. And so, without children in our schools, educators have been thinking about what schools truly are.

If schools are no longer defined by buildings or physical structures, if they are not about gathering together young people under one roof, if they are not about noise and bustle and shared activity - then what are they? And what is teaching, if the freedom we once had to roam the classroom, to crouch beside the struggler, to eyeball the transgressor or step into the space of the sad and support them, has been temporarily taken from us?

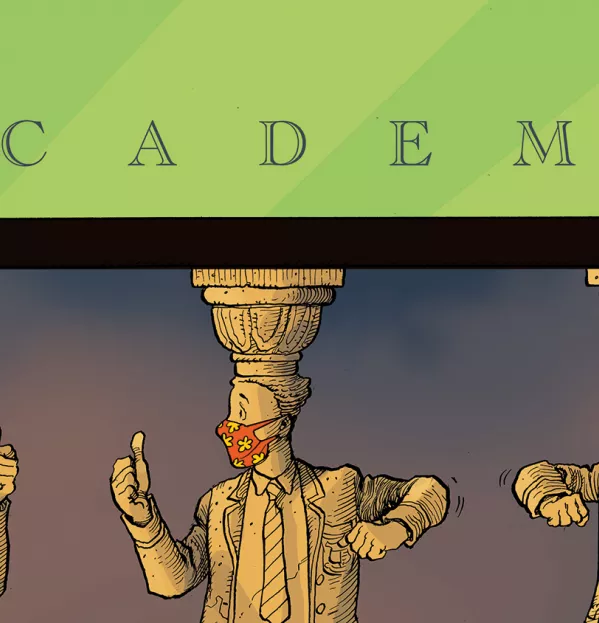

When you take away the shell, what remains at the heart of a school? In my view, it is its culture, and a school that can create an active, thriving culture will therefore continue to thrive through any pandemic, no matter how lengthy, because each student - despite sitting individually and separately in their own bedroom as they learn - is still at school. They instinctively understand and feel what being part of that school means and what the corresponding values-driven expectations of them are.

In A Manifesto for Excellence in Schools, by academies chief executive Rob Carpenter, we read: “Learning is inherently a social process, so as a school, improvement is dependent on working together. When learning is social, we unlock our own and each other’s creativity, are motivated because great work is done together, and grow stronger because of the interdependence we have on each other’s ideas, generously shared and valued.”

A school is all about culture and ethos

As a manifesto for a staff body, that’s pretty powerful. But as a manifesto for a classroom, it’s nuclear. It sums up that each of our classes is a small, interdependent network of people, sharing and valuing each other’s ideas in order to improve.

And, if learning is social in this particular way, then the creation of an atmosphere and learning identity for each of our classes - the building of that team - is crucially important. We’re not just teaching a set of individuals who happen to be in a group together because we can’t afford to educate everyone individually, as this country’s fixation with differentiation might lead us to believe.

Rather, the strength lies in the very fact of the group itself, and it is therefore our job to find out how that group will tick, how it will work together toward that “interdependent network of people” of which Carpenter writes.

Perhaps this is why, famously, John Hattie’s research on class size led him to the conclusion that it makes little to no difference: because it is the group atmosphere, the joy of learning created by the teacher who loves teaching, that counts - not how much individual attention is given to them.

Shared endeavour

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be encouraging independent learning - quite the opposite. Instead, the group dynamic is created where the notion of individual exploration is encouraged - is the very air that is breathed - with everyone buying into this shared endeavour.

For example, differentiating our questions as practitioners, so that individuals are catered for, is often considered the holy grail. But how much more effective would it be to create a questioning culture? If students are encouraged to ask questions of each other, without it seeming uncomfortable or awkward; if they are accustomed to your responding with, “Well, what do you think?” when they ask you a question; if they are used to your reframing their questions with, “Is there a better question you could ask here?” ; if - even better - they are used to your writing one word up on the board and then asking, “What am I going to ask you about this?” - all that builds toward a shared culture of questioning and curiosity.

And this creation of a shared culture has to be more important now than ever because, without physically being together, we needed to hang on to the feeling of learning as a social, human feeling. We couldn’t always be with each other but we could absolutely keep the culture of each of our individual classes - and thus the culture of our schools - alive.

As author Robert Pirsig says in his book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: “If a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a government but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves … There’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding.”

Schools are not buildings. They’re not people factories. They’re patterns: they’re systematic patterns of thinking and learning and being together. If we can establish, as part of a culture, the systematic pattern of thinking that teaching and learning is about joy and curiosity, questioning and wonder, then that will remain, whatever the circumstances.

And then (perhaps even more crucially, looking at what is happening in our world today) it must be our duty to establish a culture that looks to those young people’s later lives, and the contributions they will go on to make to their own communities and to society more generally. It is our job not just to help them to learn but to help them to develop an inner compass of values to guide them - a compass they develop because of their school and then take with them, instinctively, for the rest of their lives; values of integrity, of self-belief tempered by humility, of strength that is equated with compassion. We must equip those of our young people lucky enough to have access to outstanding education with what they will need, not just themselves to thrive and to be happy and successful but to allow others to do so, as they look to shape a more equitable world for all.

The Slinky toy

I have been reading a book called Thinking in Systems: A Primer, edited by the Sustainability Institute, which brings together - posthumously - the work of an environmental scientist called Donella Meadows. It’s about finding patterns in scientific research and thinking that help us to consider the communities we lead and live in.

In it, Meadows writes this: “Early on in teaching about systems, I often bring out a Slinky. In case you grew up without one, a Slinky is a toy - a long, loose spring that can be made to bounce up and down, or pour back and forth from hand to hand, or walk itself downstairs.

“I perch the Slinky on one upturned palm. With the fingers of the other hand, I grasp it from the top, partway down its coils. Then I pull the bottom hand away.

“The lower end of the Slinky drops, bounces back up again, yo-yos up and down, suspended from my fingers above. ‘What made the Slinky bounce up and down like that?’ I ask students. ‘Your hand. You took your hand away,’ they say.

“So I pick up the box the Slinky came in and hold it the same way, posed on a flattened palm, held from above by the fingers of the other hand,” Meadows continues. “With as much dramatic flourish as I can muster, I pull the lower hand away. Nothing happens. The box just hangs there, of course. ‘Now once again. What made the Slinky bounce up and down?’”

The answer to Meadows’ question clearly lies within the Slinky itself. The hands that hold it release some behaviour that is latent within the structure of the spring. And that is what a school really is. It’s first of all that guiding hand: the hand that shapes each spring within a shared culture, so that it develops within each and every student who attends our school, and then stays within them as they step out into the wider world, away from our direct guidance.

While they are in school, they have the benefit of our guiding hand. But, eventually, we must let them go - releasing them, just like those Slinkies - and trust that they will propel themselves with purpose and energy, going on to think, explore and behave to others in the ways their school culture has encouraged them to.

Fionnuala Kennedy is head of Wimbledon High School, part of the Girls’ Day School Trust

This article originally appeared in the 23 April 2021 issue under the headline “More than bricks and mortar”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters