- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Will artificial intelligence be a force for good in education?

Will artificial intelligence be a force for good in education?

- This is an abridged and updated version of “Algorithm’s gonna get you”, originally published in Tes magazine on 26 May 2017. You can read the full version of the original feature here.

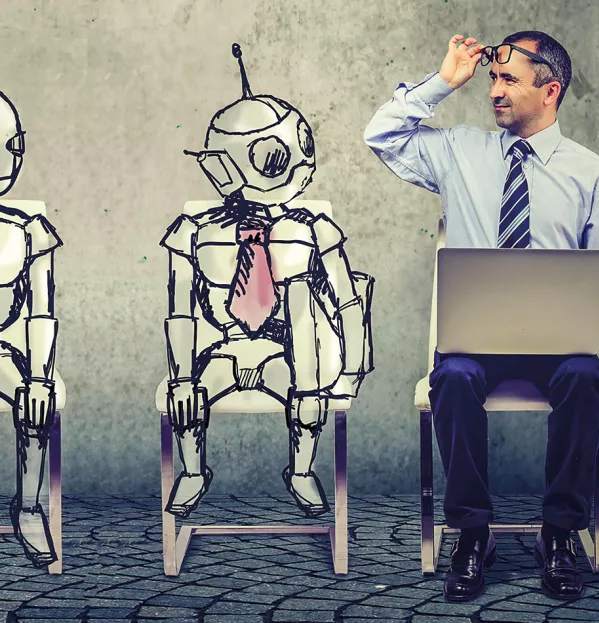

Let’s get this straight: robot teachers are not going to steal your job. Artificial intelligence (AI) could, however, fundamentally change what teachers do.

How? Well, it could be used to support learning at any age, says Rose Luckin, professor of learner-centred design at the UCL Knowledge Lab in London.

There are already great examples to draw on here. Ashok Goel, a computing professor from the US, stunned his students when he revealed that a teaching assistant they’d been messaging all year was an AI chatbot. The chatbot system answered simple but common questions around the syllabus, deadlines and assignments with a 97 per cent certainty, while sending unanswerable questions over to human TAs.

Meanwhile, others are using AI to create personalised learning experiences. Century Tech, for example, has built a system that sees students log in and work on a learning platform, while the technology collects intricate data on skills and knowledge. That data can be used to inform lesson planning and assessment and, according to Century Tech, saves teachers hours each week, allowing them to concentrate on teaching.

So, AI might save time - and reduce stress - but some teachers fear they will be reduced to crowd control while their students beaver away online. Those fears are unfounded, says Priya Lakhani OBE, founder and CEO of UK-based Century Tech.

“The benefits are around augmenting the skills of the teachers; they’re absolutely not replacing them, but instead finding ways teachers can use their uniquely human skills more effectively,” she says.

AI-integrated education might sound less gimmicky and more procedural than you imagined, and while it makes for less dramatic headlines, the effect on students and teachers could be huge.

Of course, those effects could be negative as well as positive. You see, when it comes to using machine learning, such as language-based tools like chatbots, AI is only as good as the data fed into it. A lot of education data is highly suspect; if it’s human data, it will come with human variables. For example, how does the AI recognise why a student is performing in a certain way on any given day?

Any number of issues could impact performance, yet the data will only tell one story. Human biases will be problematic, too. These biases might not be explicit, or even conscious, but they’re there in the data that’s used to “train” AIs.

There are other reasons to be cautious when it comes to artificial intelligence. With stories of data breaches and hacking hitting the headlines, it’s commonly said there are two types of companies: those who have had a data breach and those who haven’t yet.

Luckin does have some concerns. Because algorithms are designed by people, she says, they “therefore run the risk of being biased”. She agrees that the market for personal data is a “huge worry” and that data security is also a challenge.

But she thinks that educating the public about these issues is the best form of defence, rather than ignoring AI altogether. She stresses that with the right “vision, culture and safeguards”, artificial intelligence can be a force for good. However, its challenge is to win over “hearts and minds”. AI doesn’t just need people to believe it works - it needs people to trust it, to believe that it does not endanger the relationship of trust between students and teachers.

For advocates of artificial intelligence in education, this will be the real battle if the potential negatives are going to be overlooked for, what some believe, are the life-changing benefits.

Kat Arney is a freelance writer

Commentary: ‘We can set the direction’

Rose Luckin is professor of learner-centred design at the University College London Knowledge Lab. She says:

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, technology has become an even bigger part of our daily lives. Edtech companies provided very attractive deals to schools, which has led to many systems mentioned in Kat Arney’s original article being used more in education.

On the one hand, this is positive, as it means that teachers have more practical experience of using technology that employs AI. But many fears still remain. There’s a general unease about data and privacy, and I often hear from teachers who have concerns about AI not taking their jobs, but reducing the status of human teachers.

Those concerns are understandable, given that teachers are not taught about AI in an accessible way. The companies who are making a fortune out of it don’t want the public to understand it, because that’s not in their interest. And while there has been some very welcome investment into setting up more courses on how to build AI, nobody’s investing in a concerted effort to educate people about what modern machine learning AI does and how, what the risks are, and what benefits it can bring.

This needs to change. AI is a part of our world, and it’s not going away. So, we need to do something to help bridge the gap. For me, it’s about brokering good relationships between educators and developers, so they can have useful conversations: teachers can help the edtech companies to understand more about education and vice versa.

I always say to teachers: if a company can’t explain to you what their AI does in a way you understand, don’t buy it. They need to be able to. That would be such a good way forward. If we could set up a framework whereby educators and developers work together, we’d end up with much better AI and a more knowledgeable educational workforce as well.

The good news is that we are still early enough in the evolution of this technology that we can set the direction for it.

Technology within AI is increasing in sophistication all the time, and there will be more and more different ways that AI can help us in education. It is a benefit we don’t want to lose, so it really is worth spending the time to get it right.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article