- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Primary

- Anxiety in primary schools: how to understand and tackle it

Anxiety in primary schools: how to understand and tackle it

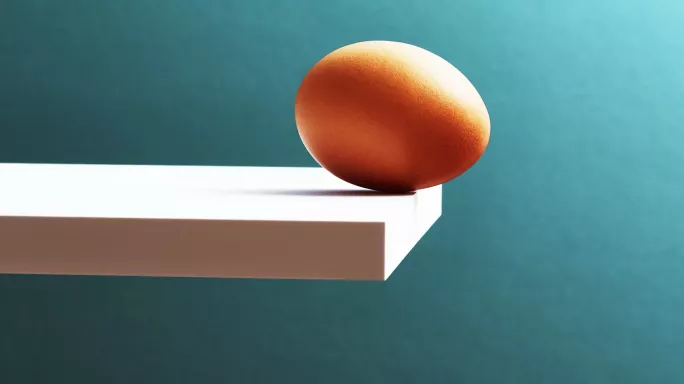

Anxiety in schools was on the increase before Covid-19, was exacerbated by the pandemic and is now the subject of increasing concern.

Reasons include war, the cost of living, global warming, media doom and gloom about the future, and, as cited by Jonathan Haidt in his book The Anxious Generation, the overwhelming influence of social media.

Camhs can’t cope with a backlog of referrals and GPs, according to a report by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (2022), are having to breach NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines in prescribing medication for under 18s.

Primary teachers increasingly have to manage severe emotional dysregulation, let alone generalised anxiety, panic attacks and school refusers. According to hands raised on our courses, self-harming and online bullying are now affecting primary-aged children.

After the pandemic, I got together with Dr Angela Evans, a child and adolescent psychotherapist who practices privately and who worked for Camhs for 20 years, and Kate Moss, a headteacher with a therapy background who runs a school (Clearwater Academy in Gloucester) with a tangibly contained and compassionate culture.

We wanted to see what we could do to help primary teachers manage and survive this anxious world.

We wrote a book, devised a one-day course and ran a three-day action research project in Sutton (a local authority with high numbers of mental health issues), asking teachers to experiment with strategies we gave them to reduce anxiety in the classroom. The outcomes have been exciting and heartwarming.

The book, just published (details are at the end of this article), is divided into four sections: why is everyone so anxious and what can we do about it; understanding and dealing with extreme behaviour; supporting the learning to reduce anxiety; and creating a containing and compassionate school.

Below, we reveal a key message from each of those sections.

1. Understanding how anxiety is projected

As part of our work, we ask teachers to name the emotions they experience when, for instance, an angry parent is confronting them.

They say: upset, ashamed, anxious, angry, overwhelmed, confused, inadequate. Angela explains that the parent is likely feeling all those emotions, too, and is successfully projecting them onto the teacher, although all the teacher sees is anger.

We can apply this to any projection from a child or adult. Understanding how emotions and often hidden feelings are projected in the classroom helps us to know how to react to them and helps children feel safe and contained.

Bion (1962) developed the theory of containment, where he described the mother’s capacity to act as a container for the infant’s projections, to make sense of them, to transform them and to come back to the infant with reassurance and comfort. He explains that this contains the infant’s anxiety and regulates their extreme emotions.

“Containing” adults listen, acknowledge emotions, provide reassurance and empathy, and let the child or adult know they are cared for and being kept in mind (“I can see you are feeling upset…”).

Children need to know they are still lovable before talk ensues about any extreme behaviour, for instance, or their shame and anger stop them from being able to think and process.

For challenging children, containment is a vital function of schools and both adults and children need to feel contained, with containment rippling down from school leaders to all adults and then children.

If a class teacher feels contained, they’ll manage to contain a child’s projections much more easily, nipping things in the bud, leading to the classroom being a safer place emotionally so that children can learn more easily.

2. The psychology of extreme behaviour

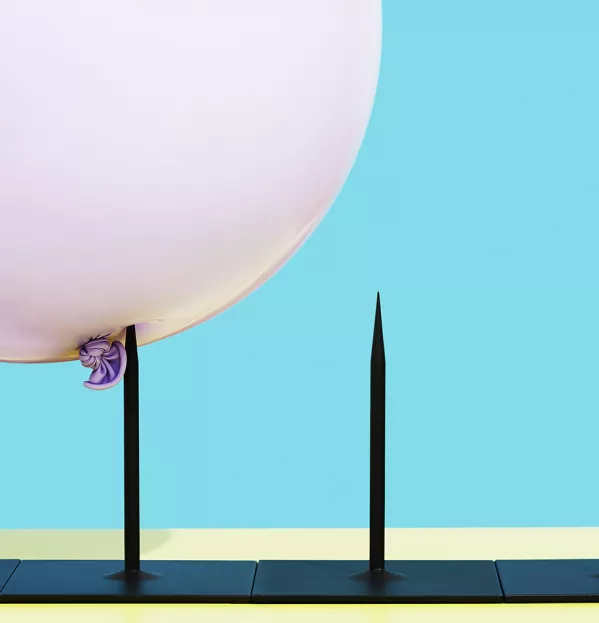

Attachment theory and attachment styles are crucial to understanding extreme behaviour that can have anxiety as a key contributor. The most extreme attachment style is “insecure”, which is a disorganised, controlling and/or traumatised attachment style.

These children can find no organised way of staying safe. They cannot seek attention, they cannot withdraw, they cannot smile, and when under two years old they cannot even run.

Thus, their behaviour and reactions to stay safe are a disorganised array of pathological responses triggered by the fight/flight/freeze response.

These children might be:

- Underachieving

- Anxious

- Very controlling

- Over-reactive

- Over-sensitive

- Unable to understand, distinguish or control emotions in self or others

- Experiencing strong, overwhelming feelings

- Depressed

- Switched off

- Violently angry

- Anxiously dependent.

What they need is:

- To know they’re in your mind through frequent, direct one-to-one interaction

- One-to-one time is essential

- A network of adults around the child

- Absolute clarity about rules

- Structured activities in class and break times

- Help with all transitions as they can be a trigger for an outburst

- To feel safe

- A curriculum that incorporates issues such as how to keep safe, and managing big feelings and dangerous feelings.

One of the most challenging roles for the teacher is managing your emotions so the children can manage their own. What follows is a good example of a common incident and how you might manage yourself in that moment.

Step one: If a child has an outburst of anger, either physical or verbal, alone, in a small group or in the classroom, that child will not be responsive to reason. Keep the child and others safe. Have two adults readily available at all times. Have an open-door policy in classrooms. But if possible and safe, let that outburst happen.

Step two: As the adult, you may become aware of overwhelming emotions and/or physical symptoms in response to this incident. Note your symptoms and emotions, hold them, breathe and meet the child’s emotions and behaviour with calm.

Step three: When the child begins to calm down, help the child to breathe, take their mind elsewhere, take them for a walk. Young children still need help to regulate their emotions.

Step four: And then after the incident. The educator needs to self-reflect on what happened to them or to speak with a colleague. Process your emotions. The educator should then speak and listen to the child who had the outburst, to help them to reflect on the event and to think about what they can learn from it. Take care not to induce shame. Note your tone of voice and non-verbal messages as you interact with them.

The educator needs to attend to other children who might have been affected, to reassure them and to help them to understand what happened. And to speak with parents/carers and listen to them with compassion and respect.

3. Adapting formative assessment

One of the reasons I wanted to write this book was because of how often the feedback from my learning teams included “reduced anxiety” as a result of using various formative assessment strategies.

There are elements that specifically reduce anxiety, starting with raising children’s self-efficacy (their belief in their ability to achieve); normalising error (“marvellous mistakes”) so that children see how we learn from them; giving task- not ego-related praise (“Well done - you’ve put a capital letter and a full stop” rather than “Clever boy”) so that children see they are all achieving; eliminating comparative rewards so that the learning becomes the main focus and children are not made to feel complacent or demoralised; having mixed ability via random learning partners or trios changing weekly so that children have a range of social and cognitive learning experiences and develop mutual respect and the ability to work with anyone.

Putting these strategies into place led to teachers saying children were less anxious and more confident to ask for help, to reveal their errors and misconceptions, and to help each other.

Moving on from frameworks for learning that reduce children’s fear and anxiety, we wanted to explore how teachers could engage children in discussions about difficult emotions within class lessons. We suggest specific ways in which themes of anger, guilt, loss and so on can be integrated throughout the curriculum.

Examples are given, for instance, of tackling punctuation for speech through analysis of an excerpt from the book The Boy at the Back of the Class concerning a refugee who joins a class, and the dialogue that ensues between two of the characters.

Letter writing is explored via the book The Iron Man in which one of the characters finds it too difficult to engage with another character, so writes a letter expressing his feelings instead.

The key point is made that class discussions should focus on the actions of characters (“How do you think they felt?”) rather than asking children to reflect on their own experiences, which could create anxiety rather than reduce it.

4. Creating a compassionate school

In the book, Kate outlines the role of a school leader: a perfect combination of theory and practice. She describes, for instance, exactly how we might talk to children “sent” for misbehaviour so that they take responsibility for their actions while still feeling cared for. She includes raising teachers’ self-efficacy, being a role model, creating trust and communication, perspective and resilience, and community.

She believes in some fundamental leadership principles to create a safe and compassionate school, which are reproduced in her own words below:

Be visible

It’s so much easier to begin conversations and find out what parents really think when you’re out and about.

Use inclusive language in letters and official communications

This tends to promote togetherness. e.g. We are delighted that our children…

Bear the emotion

When someone is upset or frustrated allow them to be so. We know that we need to do this with children when they are upset, anxious or angry in order to get to a point where we can talk productively.

It is also important, however, to do this with adults.

Allow people time to let off steam without interrupting or correcting, just listen and clarify the main points the person brings. It’s so tempting to try to shut a conversation down, particularly an angry parent, in an effort to make the problem go away.

If you immediately respond with a counterargument, however, the person will feel that you are not listening, that you haven’t appreciated how much the issue is a concern and it will catapult you into opposing corners.

Experience has shown me that people tend to have a natural time limit when expressing very strong emotions, which is around 10 minutes. After this time, they will be far more receptive to a rational discussion of the problem.

The emotion will have dissipated somewhat, leaving space for exploration. Rather than finding yourself fighting with the person, you can work together to find a solution. Just knowing that the outburst will not go on forever is hugely helpful and lessens the stress response in ourselves.

Try not to judge

Just as children who are grouped by ability know exactly what the teacher thinks of their intelligence, so too can parents tell if teachers and office staff are judging them. This is the opposite of feeling included within a community and, at its extreme, sets up an “us and them” situation.

Don’t assume that your staff will see or appreciate the complexities of different families’ lives, as we know we can only see the world through the experiences that we have been through. Sometimes it is helpful to ask a staff member who is struggling with a particular parent to step into their shoes so that they can truly see and feel the parent’s world.

Anxiety among primary children and their parents will never go away but we can do so much to better support both - we hope our book goes a long way to helping you achieve that in your school.

Shirley Clarke is an international expert in formative assessment, a researcher and a former teacher. She co-wrote the new book Understanding and Reducing Anxiety in the Primary School with Dr Angela Evans, a child and adolescent psychotherapist who practices privately and who worked for Camhs for 20 years, and Kate Moss, a headteacher. The book is out now.

Tes readers can get a 20 per cent discount on Understanding and Reducing Anxiety in the Primary School by ordering here and using the discount code TES24 (valid until 11 December 2024)

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article