Another year, and another mountain of competitions. English is such a wide-ranging subject, embracing a variety of topics and genres, so the competitions on offer can be anything from poetry-writing to writing articles on themes linked to community service, significant current events or historical anniversaries. And there are always invitations to submit creative writing on a theme for inclusion in an anthology.

Everyone wants a slice of our pupils’ creativity, it would seem. At best, it’s irritating. But producing material for external competitions and anthologies can consume a great deal of extra time and effort on the part of teachers and learners - time and effort which might have been better directed elsewhere, such as the curriculum.

It’s not my intention to deprive today’s youth of rivalrous experience. I even have to admit to possessing a competitive streak myself. Winning a selection tin of chocolate bars in a Cadbury’s essay competition at the age of 8 was unforgettable in that pre-five-a-day era.

And, at the risk of partly undermining my own argument, I admit there are competitions which are genuinely worth entering. Every year I find it so inspiring to see students prepare for public speaking competitions, such as the Rotary’s “Youth Speaks”, which has been going for decades. It’s a genuine learning journey which embraces the creation of a topic, research, construction of a speech and then performance - not to mention teamwork. The best part of it is the genuine interest that Rotarians show in the individual members of the team and their chosen topics. It’s great for young people to be able to converse on more equal terms with adults who have been successful in a number of fields.

The teacher workload burden

No, what I object to is that many of the competitive opportunities that cross my inbox and enter my pigeon-hole invade my free time, for little or no return.

It seems that when embarking on a consciousness-raising exercise or attempting to raise their public profile, a marketing department for a charity or education-related enterprise will quickly flick the default switch of running a competition. It may be cutting edge to the originators; but to those of us on the receiving end, it’s lazy thinking and a displacement of effort and cost.

Once the competition is set up at their end, the company can just sit back and wait for a few entries to come in. All that is left to do is sort through lots of hopeful children’s writing: poems, stories and articles, all of which have been “selected” by teachers already.

It’s an instant workload inflator, especially where, not unsurprisingly, children have invested a lot of time and would like feedback. With the growth of the accountability culture, there is the risk that a lengthy rationale behind selection in-school will be needed in the interests of “transparency” to justify the entries that go forward and represent the school. More written feedback!

For the organisers, it’s a much easier task - the judge’s decision is final and the company will not enter into any correspondence with the entrants. Usually, only the handful of prize-winners gets the in-depth critique of their work - everybody else receives generic feedback.

The advantages to the marketers are all too clear. Little investment is involved - only a couple of prizes to the lucky winners, limiting the financial outlay. After all, it’s the very essence of competition that not all shall have prizes. Often the main prize is the kudos associated with winning, and the glossy press releases of successful pupils. This may be good for marketing; but when the educational landscape is littered with competitions, it’s very easy for your school’s victory to get lost in the multitude.

The result is a neat redistribution of cost and effort from the marketers to the educationalists.

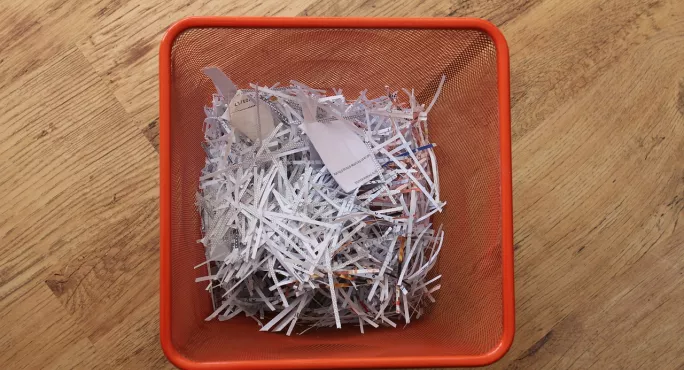

The only strategy to circumvent this disaster involves swift dispatch of competition material to the real or cyber bin.

Yvonne Williams is a head of English and drama at a school in the South of England