- Home

- Book review: Stand Up Straight

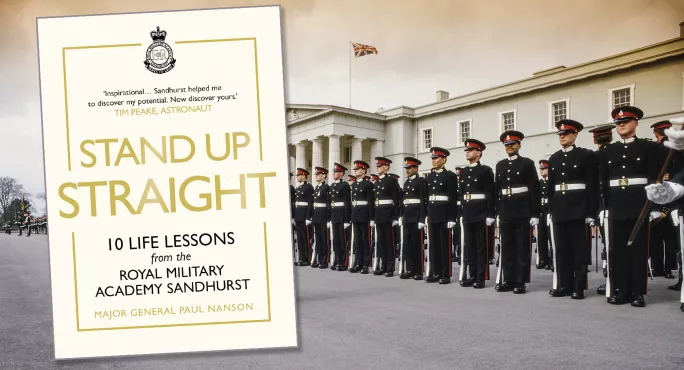

Book review: Stand Up Straight

Stand Up Straight: 10 life lessons from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

Author: Major General Paul Nanson

Publisher: Century

Details: 160pp; £12.99

ISBN: 9781529124811

New teachers have it tough. Not only are they the most monitored and tracked generation of teachers ever, but they also have to climb over a mountain of edu-books that seems to grow every day.

As a PGCE student, my reading list included such exotic names as Vygotsky, or Piaget (whose four-stage theory of cognitive development was of curiously little interest to the Year 8s I taught on a Friday afternoon in a Portakabin on the edge of a playing field).

So wedded were my course leaders to a small selection of pedagogical texts, that we student teachers passed around copies of Michael Marland’s The Craft of the Classroom like it was samizdat literature.

Indeed, our PGCE course leader was heard to ask about an initiative whether it was “fine in practice, but does it work in theory?” I still wonder if he was joking, but suspect that, in those relentlessly dogma-driven, progressive 1990s, he wasn’t.

The reading lists were heavy in theory but light in number. How different from today.

Bewildering choice

PGCE students in 2020 must be bewildered by the choice of books publishers are mainlining to Amazon every week.

When I see on Twitter another book about to hit numerous schools’ teaching and learning libraries, I feel like Brenda during the General Election, shouting “You’re joking. Not another one. There’s too much pedagogy going on at the moment.”

The drumbeat of titles keeps coming: Teach Like A Champion, Teach Like a Pirate, Teach Like Nobody’s Watching, Teach Like Your Hair is on Fire.

(I thought of combining the last two, and write a book called Teach Like Nobody’s Watching While Your Hair is on Fire but decided that it is too disturbing, and would probably condemn me to a life of school consultancy.)

And the explosion of publishing around schools is matched only by the unstoppable rise in the number of school consultants, all of whom seem to make a very good living telling teachers how they should be doing their jobs.

A recipe for perfection

Some of those standing in front of staff at the start of term are ex-teachers and ex-headteachers. Some of them failed at the job, others succeeded, and some have never taught.

Clearly, the market shows that these books, and those consultants, are meeting a need - otherwise they would not be flourishing as they are, tweeting about their fabulous lives of marking-free, international travel.

And all are promising a recipe for perfection that is not only impossible but probably undesirable too. Mistakes and failures are endemic to teaching: we just need to learn to make the right mistakes.

What other profession would welcome so many unqualified people into their place of work and politely listen, while they were told they were doing it all wrong? Doctors? Journalists? Lawyers? I don’t think so.

We should look at ourselves, at the faith we have in our ability to do our jobs well. And we should seek to learn from each other, and to trust in our own professional judgement and experience.

Not reading about teaching

New teachers should be given reading lists that contain books that are not about teaching: such a restricted diet inevitably leads to deficient thinking.

Dissonant voices, and contrary views matter, as do new perspectives. You can become a better teacher by not reading about teaching.

We could all compile a list of non-teaching books that make us better teachers. Books by Daniel Kahneman, Andrew Solomon or Malcolm Gladwell reveal deep trends about behaviour and thinking, and allow us to think differently about ourselves and others.

And one book I would add to that list would be Stand Up Straight: 10 life lessons from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, by Major General Paul Nanson.

Nanson’s prose is not always a thing of beauty: it is direct, clipped, military-like, and no cliché is avoided if it quickly conveys the necessary meaning.

But the advice he gives is the sort that you do not learn on a PGCE course, or that is often not discussed at school.

Sitting in a ditch like a stationary target

He stresses how important it is to be early for each meeting, the importance of meticulously planning ahead, and how best to hold and project yourself in front of others (and what audience is more judgemental than a bunch of Year 10s?).

Surprisingly perhaps, he writes about how much officers are encouraged to talk to each other about their worries, and concerns. Some schools could learn a lot from this.

As in the army, failing schools invariably have dysfunctional senior management teams who do not communicate with their staff.

And he has advice for school leaders, too: right or wrong, make a decision, he says: “It is better to be doing something with momentum than sitting in a ditch like a stationary target.”

Inertia is dangerous, and that sniper called Ofsted would probably agree.

For Nanson, “Good morale is impossible without good leaders.” By “good”, he means not just efficient and decisive, but possessed with a clear moral core, because trust and honesty are essential to successful leadership.

Nanson shows us what works under the most testing conditions. Without making reductive and tired analogies between playgrounds and battlefields, the habits of mind can be applied to the pressures we face in school, under strain, with little time, and with judgements always pending.

Whether you are an NQT, a middle manager or a member of SLT, Nanson’s succinct text is light and portable, can be packed into a Bergen and will travel far with you.

David James is deputy head (academic) of an independent school in the South of England. He tweets @drdavidajames

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters