I’ll start with a confession: I am a 33-year-old English teacher from the Highlands who, up to now, has never been to a Burns supper.

Second confession: when I was asked to give the Immortal Memory speech at my wonderful school’s annual Burns supper for the local community, I had absolutely no idea what it meant. I nodded enthusiastically and then did what all self-respecting adults do: I asked Google.

It helpfully explained that I had to celebrate Burns’ “enduring spirit”. Next natural step, which all men who know anything are aware of, was to ask my wife for help.

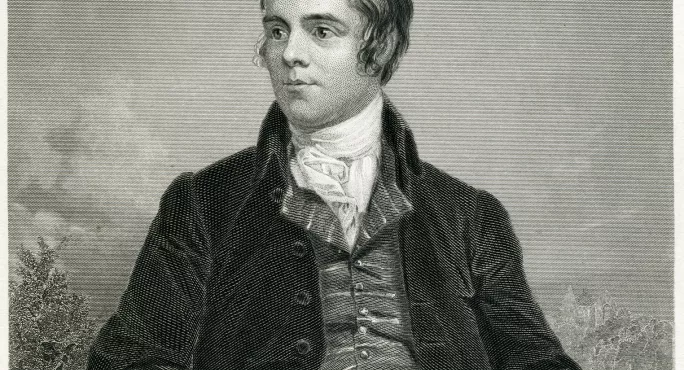

Robert Burns: His impact on Scottish culture still resonates in schools today

Scots language: Why it should be part of everyday teaching

Quick read: Scots language in the classroom

Gaelic-medium education: Gaelic becomes default language for island pupils

“Ah, Rabbie Burns,” she smiled, before launching into a word-perfect rendition of To a Mouse. This is the same wife who is a government economist, and who likes to frequently remind me how “ambivalent” she is about poetry. It turns out that in Primary 3, her class were all challenged to learn and perform the poem by heart. The finest performer would walk away with the glittering prize of a Mars bar.

Once I had recovered from the shock, I began a week of Robert Burns investigation. One of the privileges of being a teacher is the sheer volume of people we interact with on a daily basis, from all walks of life. Each first lesson with all my year groups started with a “Burning Memory” task, which asked students to record their memories of Burns and his work.

Be it Ethan’s face lighting up as he recounted his performance of Address to a Haggis or Mia as she recalled lifting the trophy for singing a Burns song, most young people could account for a Burns moment in their life. Many involved them conquering a public-speaking fear, or investing hours learning a piece off by heart.

In short: their Burning Memories represented real pride.

What a wonderful thing to give young people: the chance to shine, to conquer an exotic tongue and be proud of their heritage. A chance to demystify poetry, and to recognise just how powerful words can be. And, as my wife so clearly illustrates, these “Burning” memories will remain for decades, becoming an essential part of what it means to grow up and be educated in Scotland.

Another touching moment of this Burns odyssey was when Gustavo, a student from Brazil whose English is faltering, decided he wanted to understand what all the fuss was about. During a reading lesson in the library, he took it upon himself to challenge my wife and learn the opening two stanzas of To a Mouse. His performance earned him a spontaneous round of applause (and a Mars bar). Another immortal memory formed.

I’ll end with another confession: I will be a regular attender of Burns suppers from now on.

Jamie Thom is a teacher of English in Scotland, who previously worked in schools in England. His book A Quiet Education will be published in February. He tweets @teachgratitude1