- Home

- The cane for ‘being a nuisance’ - how far have we really come since the dark days of corporal punishment?

The cane for ‘being a nuisance’ - how far have we really come since the dark days of corporal punishment?

Our school celebrated its 50th anniversary last year and, as you would expect, there was a cake, a party, music, a mayor and plenty of former students and parents. Amid all of the celebrations, we reflected on the evolution of the school and of society in that period of time with the help of lots of photos and some historical documents. For instance, I learned that we started life as an ESN school; ESN standing for Educationally Subnormal.

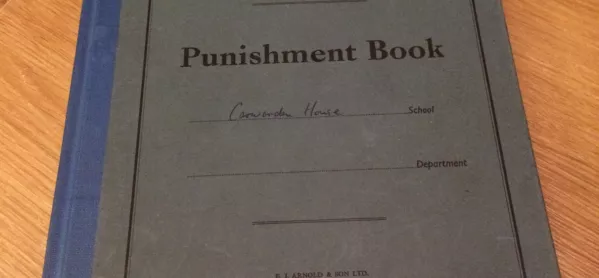

There are two documents in my desk at school that are priceless historical gems and they show what life was like here in the 1960s: our school’s punishment book and our school’s log book.

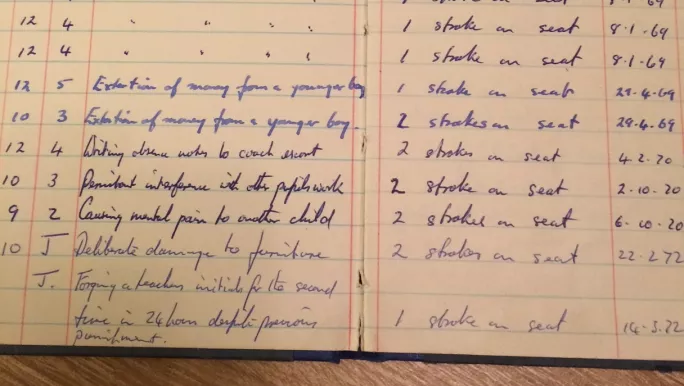

The former is shocking to read. As the name suggests, it is the record of punishments administered in the school, but it only refers specifically to the use of the cane. Corporal punishment was first recorded in the school in 1966 and was last used in 1982. In that 16-year period every single use of corporal punishment is against a boy. This is, and always has been, a mixed school.

Offences (that was the term used) range from “Being a nuisance” to “Smoking AGAIN!” to the rather more serious: “Hitting a low IQ girl”, “Stripping a girl in the woods” and “Removing a chair from under a physically handicapped girl”.

Students reappear in it time after time, sometimes for the same misdemeanours, as evidenced by the “AGAIN!” tagged on to some entries.

Misguided practice

The notion that the presence of the cane was a deterrent is based on the offensive idea that children are predisposed to misbehaviour, bullying or violence by default. This implies children will be completely unable to help themselves from doing the wrong thing unless the threat of physical punishment is there to convince them otherwise. Anyone who has worked in schools for children social, emotional and mental health needs knows how ridiculous that is.

I am also baffled by the illogical nature of the thought process: “You have committed an act of violence against another human being. In order to show you that it is wrong and that you musn’t do it again, even though you have done it many times before, I am now going to commit an act of violence upon you.”

Thankfully, almost all of us now regard the use of violence against a child as a punishment, a deterrent, or a way of improving a child’s behaviour to be both cack-handed and abhorrent. I say most, as I still meet teachers, thankfully rarely, who mourn the fact that we are no longer allowed to hit children.

So what will we regard as anachronistic, ineffective or abhorrent in behaviour management in 50 years from now?

Perhaps we will have long ago dispensed with the zero sum mentality of I win/you lose and we will see the development of behaviour as a teaching and learning issue in the same way that we do with reading, say. Instead of expecting children to just ‘get’ how to behave, we will take a more developmental approach to enabling children to deal with real-life difficulties, such as conflict, anger, fear and failure. As the late Joe Bower said “Doing well is always more desirable than not doing well, so when a child is not doing well, it is likely that their environment is demanding skills they are lagging.”

More work to be done

We will regard it as obvious that we will need to respond to a child’s behaviour in a way that is appropriate to the level of developmental maturity the child has attained, that is to say that we will start from where the child is at, as we would obviously do when teaching the concept of number.

Teachers will look quizzically as they hear that we liberally and ineffectively used detentions as a means of improving behaviour or of deterring poor behaviour. They will regard as irrational our expectation that by depriving a child of their liberty for a short period of time the child with then somehow know what he right thing to do next time is.

I hope that I’ll be celebrating that we no longer regard exclusion as an effective means of improving behaviour - it isn’t - and that its use has long since ceased. We will take the reasoning from above that the “environment is demanding skills they are lagging” and see as illogical the idea that time away from school, away from peers and away from learning can somehow fill by magic the skills gap that the child has.

We will have embraced much more widely the use of restorative practices that some schools have adopted as standard. We will consign to the history books the use of ineffective strategies as we realise, as we do now with corporal punishment, that it is merely the illusion of action. Finally, doing something, anything, because it sounds tough will be a thing of the past.

Jarlath O’Brien is headteacher at Carwarden House Community School, Surrey

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters