- Home

- GCSE resits: How will students fare this summer?

GCSE resits: How will students fare this summer?

For many colleges, their GCSE English and maths retake students account for their largest exam numbers. In a year when the exam system has been turned upside down, how will they fare?

Preparing post-16 students to retake GCSE English or maths is one of the most challenging and potentially most rewarding tasks that colleges take on. Their students have not yet achieved the all-important grade 4 in these vital subjects and will often have started the year saying “I can’t do this” or “I don’t want to do this”. In a few short months, they are expected to re-engage, remotivate and help students overcome their sense of failure and turn things around.

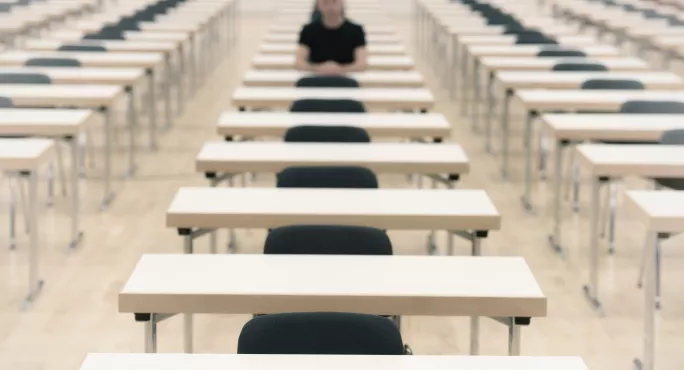

The plate-spinning required includes building confidence, identifying individual gaps and misconceptions, reteaching for understanding and constant practice and feedback. So far, so exhausting. But in the end, much will depend on students’ performance on the day as well as the fluctuations of grade boundaries. Once students enter the exam room, one can only hope that their improved fluency in some areas will make up for any weaknesses in others. But at least, in a normal year, the students are all sitting the same public exams, a national assessment process has taken over and their work will be marked and moderated in a standardised way.

News: Should FE expect 120,000 extra resit students?

GCSEs: The challenge of ranking thousands of students

More: Is AI the secret to improving GCSE resit pass rates?

The post-16 GCSE retake cohort poses a particular challenge for our exam system. It’s a large group - 30 per cent of young people don’t achieve a grade 4 or above first time around. Virtually all are studying in colleges and in most colleges the numbers entered each year are eye-wateringly large, often in the thousands.

The GCSE resits cliff edge

These students don’t have a standard profile but do have lower prior achievement overall, concentrated around grades 2 and 3. By definition, large numbers of these students will be working at the grade 3/4 boundary and this bunching means that very small changes to that boundary can affect a lot of candidates. The importance of this boundary makes it a cliff edge: achieving grade 4 is mission accomplished and anything less means try again later.

Normally, GCSE grade boundaries are defined in relation to the Year 11 age cohort. Every Year 11 student takes GCSE English and maths. There is a roughly similar grade distribution each year and therefore some limit to how many are likely to achieve grade 4 or above. Retake students sit the same exams but are not a representative sample so don’t contribute to the standard setting. With no ceiling on how many could get the marks needed for a grade 4, it’s a tough challenge but it’s not a zero-sum game.

Coronavirus: The impact on exams

But this year it’s different, the cancellation of exams has brought new processes and new uncertainties for staff and students. In a matter a few weeks this spring, a new system had to be developed, with teachers coming to the rescue with Centre Assessed Grades (CAGs) and rankings for every student in every subject, supplying much of the data which will contribute to their students’ grades.

This process in colleges was evidence-based, with plenty of robust challenge and careful moderation to ensure standardisation between groups and even between campuses. In large centres, the rankings provided a level of granularity in distinguishing between candidates which exam marks themselves wouldn’t normally achieve.

Now all this is done, the crucial question is: how will standards for the retake cohort be set across the country in the absence of a common exam to read-across from Year 11 to post-16? Previous centre and candidate results will be used as a guide to what results would be expected and CAGs will be adjusted accordingly. This is reasonable where cohorts and results are stable and predictable. However, previous post-16 retake results are not a reliable guide to future achievement.

Since the introduction of the condition of funding and the big increase in post-16 GCSE entries, colleges have worked very hard to improve retake results. There has been a ferment of activity including national projects like the Centres for Excellence in Maths which has promoted work on motivation, engagement, mastery, mentoring, sharing good practice and research. Colleges are on a journey of improvement and many would have expected to see significant impact this year. However, such improvement is hard to extrapolate without objective evidence.

We know that overall, this year’s predictions are well above the expected national grade profile. This means that many CAGs will need to be moderated downwards. This adjustment is much less robust for the post-16 retake students because it is a partial, concentrated and less predictable cohort.

We can only hope that the CAGs submitted by centres carry real weight when compared with an expected grade profile because these reflect what teachers know about their students’ commitment and rate of improvement, and we don’t have objective indicators of why some students move from grade 3 to grade 4 in one year and others don’t. If the system requires the best fit between 2020 and previous years, with no other benchmark available, colleges will be lumbered with a historic assumption about how many of their students can make the leap to a grade 4.

Achieving a grade 4 can seem like a bit of a lottery at the best of times. As usual, we will celebrate the achievements of all retake students, while acknowledging that many may be disappointed this year, even if they have worked hard and made good progress.

Eddie Playfair is a senior policy manager at the Association of Colleges

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters