- Home

- Coronavirus is making us rethink school exams? Good

Coronavirus is making us rethink school exams? Good

One thing about coronavirus: it makes us rethink things. Some weeks back, we were blaming China’s authoritarianism for failing to control its spread. Now, that regime’s ability to impose draconian containment measures receives praise.

Nearer home, Italy - a country usually gloriously laid-back and individualistic - is locking down cities and closing everything. Oggi chiuso (closed today) is now the ubiquitous sign.

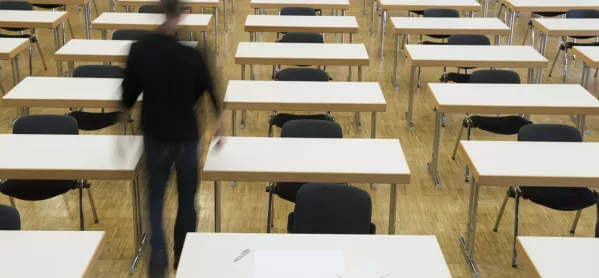

Speculation rages about what will happen to this summer’s exams if - and it remains a big if - schools and universities close. End-of-year and final exams in higher and further education, A levels, GCSEs and SATs at all levels - senior and primary - are set to be not so much disrupted as rendered impossible.

The situation has prompted renewed calls for revision of our exam system. Jenny Brown, head of City of London School for Girls, suggests scrapping GCSEs. The Times’ columnist Alice Thompson goes further, demanding root-and-branch change. That’s the better solution.

Wrestling with a bloated system

Almost my whole career in education - spanning more than 40 years - seemed to involve wrestling with exam revisions. Yet all were tinkering at best, while inexorably adding to the exam burden.

How many times have commentators (including me) noted that our bloated exam system hangs together only by a miracle, wrought by teachers and schools, and that it wouldn’t take much to cause it to implode? Coronavirus may prove to be that final straw.

Only the other week, I wrote about a suggestion from Jisc that we do away with pen-and-paper tests. Since then, at least one TV journalist has suggested glibly that, if schools were to close, exams might have to be done by computer.

If only! The current system is designed to prevent candidates from using the benefits of modern technology. Even dyslexics and those with other difficulties related to writing, although permitted to use a laptop, are forbidden such basic modern aids as spellcheck.

Our exam system is so firmly rooted in 19th-century (or, as I suggested recently, 3000-year-old) practices that this country is entirely unequipped to move it online.

A labyrinth of centralised tests

University finals, institution-based rather than part of a national framework, may be relatively easily adapted in a crisis.

If we were only talking about A levels, perhaps the scope of any solutions implemented might be manageable. This would be particularly true if papers were less obsessed with testing every part of every syllabus or specification, and instead sampled candidates’ knowledge as happened in the “good old days”, which so much other policymaking tends to hark back to.

Instead, though, we have a labyrinth of centralised national school tests at five age levels. So let’s not kid ourselves: these cannot operate this summer if schools close.

In those halcyon days to which I referred (though they were no such thing), children who missed even an entire exam through illness or bereavement might be awarded a grade based on judgements by their teachers of their progress over the preceding months or years.

That was back when we trusted teachers. Ever since Margaret Thatcher’s and John Major’s ministers (Lord Baker, Kenneth Clarke, John Patten et al) busted open what they calculatedly caricatured as the “secret gardens” of medicine and teaching, trust in professionals (and “experts”) has been undermined, and their decisions and judgements open to challenge.

Pause before jumpstarting the machine

Moreover, amid stringent targets and - in schools at least - the dire consequences of missing them or failing inspections, an argument can be mounted for suspecting that teacher judgements won’t be impartial or objective. The stakes are too high for those involved.

So now we live with this exam behemoth, a monster of over-testing that we can’t control and which constantly grows.

However, this year, in which it might not be able to function, could demonstrate that so extensive and overly complex a system is not fit for purpose, not least because it is relatively easily disrupted.

I’m not pretending that the pandemic, which is entirely undesirable, is any kind of blessing in disguise.

But, if coronavirus does indeed stop the exam juggernaut in its tracks, policymakers must pause before jumpstarting it and setting it rolling again. They must return to fundamentals, determine the very purpose and function of examining, reject what is superfluous or irrelevant.

Only after doing all that should they seek to reconstruct the structures and systems fit for a 21st-century exam system.

Bernard Trafford is a writer, educationalist, musician and former independent school headteacher. He tweets @bernardtrafford

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles