- Home

- Reopening schools: how are other countries doing it?

Reopening schools: how are other countries doing it?

After weeks of uncertainty, the government has finally announced a plan for how it hopes to get pupils back to school.

Primary schools in England will reopen on 1 June “at the earliest”, initially for pupils in Reception, Year 1 and Year 6, with plans for all primary pupils to attend before the summer holidays.

The government is also aiming for secondary pupils who are due to take exams next year (Years 10 and 12) to get at least some “face-to-face contact” with their teachers before summer.

Coronavirus: school reopenings

England is not the only nation to announce the reopening of schools: countries across the world are doing - and have done - the same. But how those reopenings have happened and the timing of those decisions varies greatly.

So what is the global picture on schools and closures?

Which countries have already gone back to school?

- In Denmark, primary schools have been open since 15 April, although secondary students will not return to school until 18 May.

- Germany has also begun to reopen schools, prioritising younger pupils and those pupils due to sit exams. Rules vary by state, with schools in some areas having opened as early as 27 April to those students sitting the equivalent of A levels.

- Austria has similarly reopened schools to pupils in their final year already, with plans for other year groups to return from the middle of May.

- France began a phased return on 11 May, starting with primary schools and nurseries. Secondary pupils between the ages of 11 and 15 living in “green zones” – areas where the infection rate is lower – will begin to return from 18 May. However, school will not resume for pupils over the age of 15 until after June.

- Switzerland, the Netherlands and Greece also began a phased return on the 11 May. In Greece, schools are open to students in their final year only.

- In Luxembourg, some senior schools returned on 4 May, with pupils being required to wear masks where two-metre social distancing requirements cannot be guaranteed. Primary schools are due to return on 25 May.

- In Asia, schools in China, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam and parts of Japan are open.

- In Israel, schools are beginning to open for elementary school pupils. However, significant numbers of parents initially chose to keep their children at home. The Times of Israel reported that only 60 per cent of eligible school children attended on 3 May, the first day of schools reopening.

- Schools in New Zealand are due to reopen on 18 May, but the Ministry of Education has said that schools “can start a transition period from Thursday 14 May”, which allows them to bring different year groups back gradually and gives them the option of providing a “transition arrangement” for those children “whose parents are anxious about their return to school”.

- Schools in Sweden have remained open. They have relied on social distancing and hygiene measures to reduce the spread of infection instead.

What is life like in a reopened school?

Germany

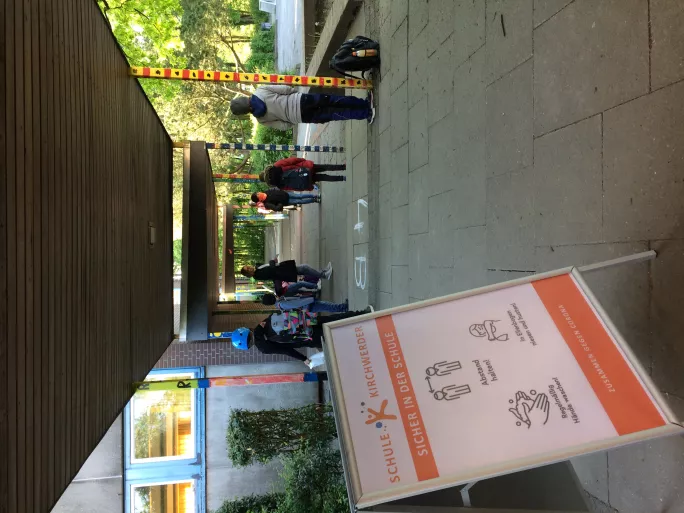

“There is no such thing as ‘Germany’ when it comes to schooling,” says Niko Gärtner, headteacher at Kirchwerder Comprehensive school in Hamburg.

In Germany, education is managed under a devolved system in which the government of each federal state is responsible for its own schools. This means that, although there are national guidelines for reopening, the timetables and nuances of doing so vary by region.

In Hamburg, for example, schools are following a three-step plan for reopening.

“First, the exam groups returned to school, preparing for and sitting their MSA (GSCE) and Abitur (A level) exams. This is happening right now,” says Gärtner.

“Also, already back in school are the year groups scheduled for leaving exams next year and those who change schools in summer (those in their last year of primary schooling)."

The remaining students will return on 25 May, but for only one full day each week.

This will allow teachers to enforce social distancing by splitting classes into smaller teaching groups and limiting the number of people in any part of the school at once.

On the days that pupils are not in school, they will continue to learn from home remotely, as they have done throughout the lockdown.

“We expect to welcome all children back, but only to run at twenty per cent capacity at any given time,” Gärtner explains. “There will [also] be additional hygiene measures in place, like designated break areas and shifts, as well as extensive cleaning and sanitising rotas.”

Pupils in exam years are also being prioritised in some other German states.

Annette Schäfer teaches Spanish and English at Marienschule Opladen school in Leverkusen in North-Rhine-Westphalia, one of the first federal states to reopen schools.

“In contrast to Bavaria, we started teaching again quite early, on 27 April,” Schäfer says.

A-level students were the first to return there and, in contrast to the UK, where this year’s grades will be determined by teacher assessments, the students have already started sitting their exams.

According to Schäfer, this has been the subject of much debate. While some politicians and students “wanted to cancel” exams, others argued that students would “face disadvantages in the future without a ‘real exam’”.

This week, following the return of the A-level students, Schäfer’s school also welcomed back students in Years 10 and 11 and the younger primary school children.

Pupils in other years are due to return from next week – although, as at Gärtner’s school, there will be strict measures in place at Marienschule Opladen to minimise the risk of transmitting Covid-19.

Normal schedules and timetables will not apply and lessons in some subjects, such as PE, have been dropped entirely, having been deemed too difficult to run whilst maintaining social distancing and hygiene measures.

Depending on the size of the class and the classroom, some groups will be split into two halves that are taught simultaneously by a teacher who has to move between two rooms. In other instances, lessons will only be taught every second week.

“A lot of creativity is needed to organise the timetable,” says Schäfer.

And, of course, there are lots of new rules, which Schäfer says pupils were drilled in before they returned: they must not hug one another; they must keep at least 1.5 metres of distance between themselves and other people at all times; they must disinfect their hands and their desk each time they enter or leave a classroom; and they must follow the one-way system that has been implemented in the corridors.

“All these rules work surprisingly well,” says Schäfer. “All students and teachers seem to follow them.”

Everyone at Schäfer’s school also has to wear a mask when entering or moving around the buildings, although teachers are not required to wear their mask during lessons, to make teaching easier.

The wearing of masks is another issue that has become somewhat “controversial” in parts of Germany, according to Gärtner.

“Our local authority has recommended [masks], but did not make wearing them mandatory – and so most of us don’t. Torn between pedagogical and ‘pandemic-al’ considerations, we have opted to not make our students feel that they are spending their days in an operating theatre guarded by faceless adults,” he says.

However, he adds, some parents are “vocally insistent” that teachers should be modelling “facial mask etiquette”.

Gärtner believes that schools need to take a “pragmatic” approach, striking a balance between prioritising physical safety and offering some level of normality for the benefit of pupils’ mental health.

“We are expecting wildly unnatural behaviour from our children and teenagers – who think themselves invulnerable, anyway – when we tell them not to jostle, touch, high five or embrace. Naturally, they will defy us the moment we aren’t looking. And I for one am not willing to turn my school into a prison yard over this,” he says.

Netherlands

“I feel as safe as I can be,” says Clair Tierney, a Year 6 teacher at The British School of Amsterdam.

“In the couple of weeks leading up to the reopening, all staff have been consulted and given the opportunity to feedback on the management’s proposals and communicate thoughts and feelings,” she explains.

Schools in the Netherlands reopened on 11 May, but pupils will attend for only half the week, continuing to spend the other half of their time learning from home.

It is up to school leaders to decide for themselves how they organise the 50 per cent teaching time, although government guidance states that arrangements must be based on full days of education “to minimise movement of pupils and parents and to fall in line with after school care as much as possible”.

In contrast to many other countries, Dutch government guidelines do not require pupils under the age of 12 to socially distance from one another.

However, the guidelines do state that school staff should keep a distance of 1.5 metres between themselves and colleagues and, as far as possible, maintain the same distance from their students.

This can be a challenge, points out Karren van Zoest, headteacher of The British School in the Netherlands.

“Of course, in the younger year groups this is almost impossible,” she says. “Especially when a child is upset or just needs some affection.”

“We have found imaginative ways to stay connected without physical touch, such as thumbs up, distance high five and creating special songs to sing, but there are times when our [EYFS] staff just need to help a child by getting physically close,” she says.

Managing the distancing requirements is easier with older children. At the junior school where Tierney teaches, they have split pupils into two groups, who attend school on different days. Each of these groups is then split into two sub-groups, who are kept separate while in school.

“Each group will be in school for two consecutive days and then at home for two days – continuing with the online home learning programme we’ve set up,” explains Tierney.

“In Year 6, where I teach, we have between 10 and 12 pupils in each sub-group. The sub-groups do not mix and are kept separate in the playground,” she says.

Sub-groups have a designated set of playground equipment to play with at break times. Each child also has their own set of classroom equipment, which only they use.

Furthermore, within each classroom, there is a designated, marked area for the teacher, which allows them to keep 1.5 metres distance from the children. The playground has also been marked to allow for appropriate distancing between groups entering the building – a measure that van Zoest’s school has likewise implemented.

In addition to distancing measures, both schools have also introduced rigorous hand-washing and cleaning routines.

“We removed all clutter from surfaces, took down any drapes from displays, and put away all soft furnishings such as cushions and cuddly toys, to ensure that the surfaces can be easily and thoroughly cleaned several times a day,” van Zoest says.

The school has agreed on a package of extra provisions with their cleaning provider, which includes extra midday cleaning of all touchpoints in the buildings – such as door handles, toilets and bannisters; disinfectant hand gel stations at every entrance; disinfectant soap dispensers at all sinks; and classroom kits of cleaning products, including disinfectant wipes, hand gel and plastic, single-use gloves.

These new routines have required a change in habits for staff, but van Zoest is pleased with how the measures are working so far.

“The way in which our school has pulled together has been incredible and after one full week of being open, I feel that we have been extremely successful. The cleaning regime and one-way systems are working well and give confidence to the staff to feel safe in school,” she says.

But what do the children make of the new approaches? According to Tierney, the pupils at her school have also coped well.

“The children who have returned are happy to see their friends and teachers and to have a routine again. They’ve adapted very well to the temporary new structure of the timetable and the measures they have to adhere to,” she says.

In part, this success may be due to the fact that the children were well prepared in advance for what would be expected of them when they returned to school.

“Teachers spent the previous week running circle times on Zoom with their class to prepare their pupils for the next few days ahead,” says Tierney.

Adequate preparation time is key for staff and parents, also, adds van Zoest. This was essential for creating trust and making sure that her school could reopen with everyone feeling as safe as possible.

What do teachers in Europe think about the UK’s plans to reopen schools?

How far can we really draw comparisons between the experiences of teachers in other European countries and the plans to reopen UK schools, though?

As a teacher in a British school abroad, Tierney is well-placed to offer an opinion. Although she feels confident that the guidelines laid out by the Dutch government and the measures put in place by her school have been made with her best interests in mind, she understands why teachers in England might not feel the same about the plans for them to return.

“Having read the document released by the UK government, I would say that the proposed measures seem to have the intentions of what the Dutch are doing but with much less clarity and articulacy,” she says.

“The major difference is that the UK document places much less emphasis on the health and safety of adults. Both the Dutch government and the British School of Amsterdam are putting both children and adults equally at the centre of their measures,” she says.

In Germany, on the other hand, Gärtner points out that it may not be realistic to draw direct comparisons between what is happening there and the current situation in the UK, simply because the two countries’ experiences of Covid-19 have been so different.

“Out of a school population of nearly 1,300 we had only one confirmed Covid-19 case so far – and for that student, the illness was largely theoretical," he says.

"Germany seems to have a very different pandemic than the UK, and if that is down to national or local public safety measures, we are and should be thankful to our government.

“It is difficult, though, to reconcile this with the lingering suspicion that children should be in school because keeping them at home exposes them to all sorts of dangers – not least persistent boredom – some of them possibly more damaging to them than Covid-19,” he adds.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters