It’s like filling up the bath without putting the plug in. That’s how one teacher described the effect of not revising properly to me when I was 15. I like this metaphor because it explains a major problem we all have when learning something new: how do we stop our new learning disappearing after just a few days?

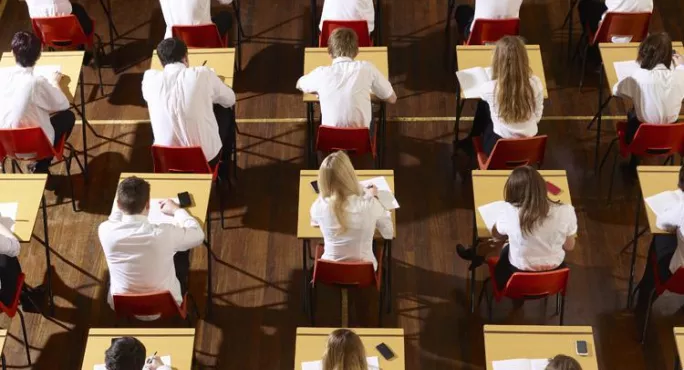

If we can extend the metaphor to breaking point, cramming for an exam is like running the bath taps full blast, topping them up with hosepipes - and still forgetting to put the plug in. Those students who did cram are now at the start of their summer holidays, and the learning bath water has long since sluiced down the memory plughole.

Both terminal exams and long summer breaks have been blamed for encouraging cramming and making it harder to remember for the long-term. One possible solution is to replace terminal exams with more frequent modular exams and coursework, which will help pupils to space out revision.

‘Banking knowledge’

The risk with this approach is in how the topics are divided up. If each module is a self-contained unit of its own, cramming becomes more likely, not less. If a pupil knows that in one exam they will only be tested on, say, Great Expectations, and that they will never be tested on Great Expectations again, the incentive is to cram all the study of the novel into the week or so before the exam. Dylan Wiliam explains the problems this can cause as follows:

“This results in what I call a ‘banking’ model of assessment in which once a student has earned a grade for an assignment, they get to keep that grade even if they subsequently forget everything they knew about this topic. It thus encourages a shallow approach to learning, and teaching.” [1]

‘Curriculum design problem’

This problem is not a pure assessment one that can be fixed by exam structure alone. Rather, it is a curriculum design problem. Instead of replacing one terminal high-stakes summative assessment with several modular high-stakes summative assessments, we should look at including low-stakes diagnostic assessments throughout the programme of study.

And if we get the curriculum design right, then the long summer holiday could serve as an opportunity, not a problem. After all, the aim of structuring the curriculum is for pupils to remember things for the long term, long after they have left school. The summer holiday can serve as a test case for that. If our curriculum design really is working, then pupils will come back to school in September retaining a lot of what they learned the previous year. In fact, when planning one year’s curriculum, we could ask ourselves what we want pupils to remember of it in September the following year, and use that to help with the planning.

Daisy Christodoulou is director of education at No More Marking and the author of Making Good Progress? and Seven Myths About Education. She tweets @daisychristo

[1] Wiliam, Dylan. What assessment can-and cannot-do. Pedagogiska Magasinet, 2011. Pedagogiska Magasinet