Exclusive: Most teachers had GCSE grade evidence gaps

A majority of teachers say at least some of their students lacked sufficient evidence for their GCSE or A-level grade this year.

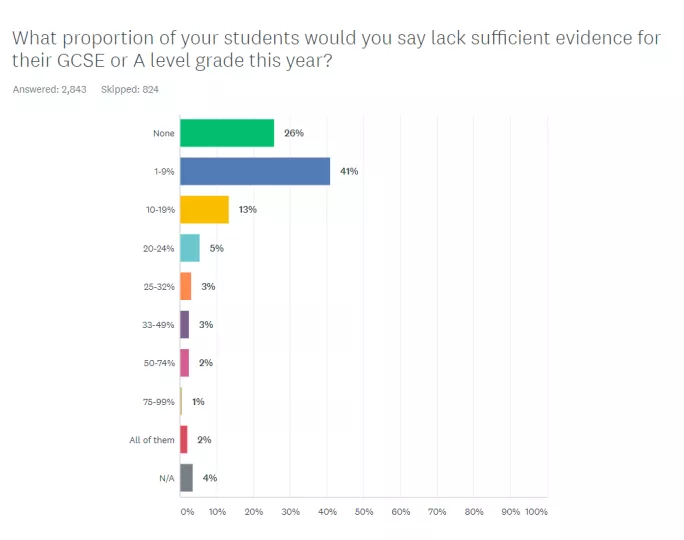

In a Tes survey of over 2,800 grading teachers, only just over a quarter (26 per cent) reported that none of their students lacked sufficient evidence to get a grade this year.

Exclusive: 2021 GCSE grades not ‘fair’, say teachers

Exclusive: Parents push teachers to raise GCSE grades

GCSEs 2021: Most teachers lose at least a week grading

But 70 per cent reported that some of their students did lack enough evidence for a teacher-assessed grade, with 41 per cent saying this affected 1 to 9 per cent of their students.

The issue appeared to affect a minority of students in most cases, with just 5 per cent of respondents reporting that over 50 per cent of their students lacked evidence for their grades.

GCSEs 2021: Students lacking evidence for teacher-assessed grades

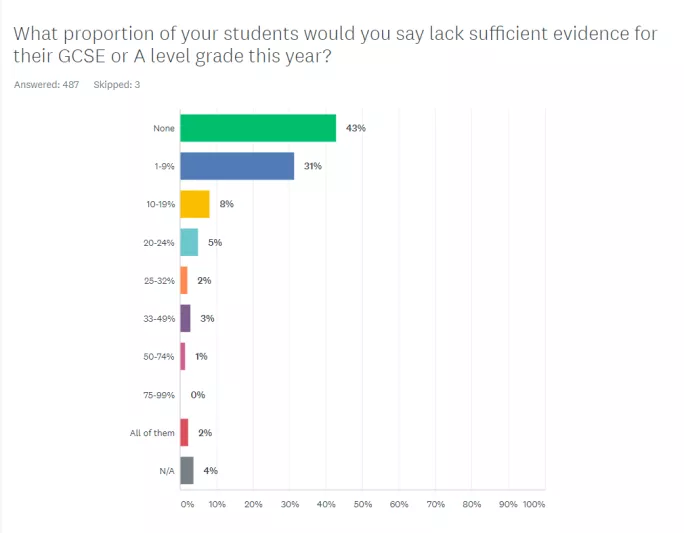

For respondents working in private schools, a higher proportion reported that none of their students lacked evidence. Of over 480 private school respondents, 43 per cent said none of their students lacked evidence.

But teachers commented that for some students, mental health issues and other disruptions had made securing a teacher-assessed grade impossible this year.

One English teacher in the state sector said they had seen “some heart-breaking cases for individual students”.

They added that one student had been unable to return to the UK from Poland since Christmas, while another had lost his mother to the coronavirus, “and his grandparents, who took him in, did not want him attending school, for obvious reasons”.

“He still has not come back on premises. He should have been a grade 7. I have no evidence other than his book from the start of the year. So tragic. So many sad stories,” they added.

Others commented that school refusers, those who were struggling with their mental health or those who had not engaged with remote learning lacked evidence for their grade.

A head of media studies, who said that between 25 and 32 per cent of their students lacked sufficient evidence, commented: “They all lack evidence in a holistic sense, because so much time has been lost.

“Of those, about a quarter have even more work missing compared with their peers, largely as a result of mental health issues. Another 10 per cent or so were taken out of the country by their families and have been uncontactable.”

And a head of social sciences, who said 10 to 19 per cent of their students were impacted by a lack of evidence, said: “Students who did not work during lockdown have had nothing to help them.

“Courses are being assessed on most of what has been taught where large chunks (almost a year) is missing. This policy has not accounted for poverty at all.”

The head of computer science at a private school, where 1 to 9 per cent of students lacked evidence, said some students had not coped well with taking tests before they were fully prepared.

“A few haven’t been able to keep up with the pressure of exams by another name done earlier with less prep than usual and have not turned up to exams,” they said.

“I’m not a subject that does big projects or bits of substantial homework that would cover the course in enough depth without just doing exams.”

Some said that students had struggled to attend school because of anxiety amid the pandemic, which had made it difficult for them to complete assessments, while students with long-term attendance issues also lacked evidence for their grades.

And where evidence existed, some teachers commented that it did not reflect students’ potential. One teacher, who said none of their students lacked evidence, added: “The quantity of evidence is not a problem.

“They have, however, been taking the assessments in normal classroom conditions, which seems to have removed some of the seriousness. Students (especially GCSE) don’t seem to have registered the importance of them, and don’t seem to understand that these are their final exams.”

‘No definition of sufficient evidence’

A head of department at an independent special school also commented: “This is difficult to answer as the exam boards have not put a specific number or requirement on the minimum amount of evidence needed.”

Earlier this year in March, OCR exam board chief executive Jill Duffy said that “there may be some young people, albeit a small number, who have lost so much learning that it will be difficult to award them a grade at all”.

Headteachers will need to have signed off that pupils have sufficient evidence for their teacher-assessed grades but the boards have not specified what “sufficient” evidence entails.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “Some students have suffered extreme circumstances over the past year and this will have sometimes resulted in limited evidence being available on which to base their assessments.

“The guidance from the Joint Council for Qualifications allowed flexibility in the evidence used in such cases, including the use of an oral assessment to assess the student’s knowledge and skills as required by the specification.

“Schools and colleges will have been best placed to make the decision on the most appropriate approach. Clearly, this is another sign of the exceptionally difficult year that has passed.

“Teachers and leaders deserve great credit for the huge amount of work that has gone into making sure that all their students receive grades which are fair and reliable, and which allow them to progress to the next stage of their lives.”

A spokesperson for Ofqual said: “In the absence of exams, we believe that teacher-assessed grades are the best approach this summer. We developed this policy thanks, in part, to thousands of teachers and school leaders who responded to our consultation, which received more than 100,000 responses.

“Exam boards provided support to teachers when they assessed and graded their students. We built in flexibility to recognise the fact that the pandemic has had a different impact on different areas of the country.

“The Joint Council for Qualifications’ guidance said that, in some limited circumstances, where other evidence was not available or possible to create, then an oral assessment could have been be an appropriate form of evidence.

“Teachers could not give a student a grade unless they had evidence on which to base the grade. Teacher-assessed grades have now been submitted, so we expect exam boards to make sure that these are based on sound evidence.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article