I once went to see an international director at a college, carrying a £120,000 contract with me that was ready to be snapped up. His response? “We don’t have time for that. We’re currently focusing all our time and resources on developing business in China and India.”

The growing vocational sectors in China and India are massive markets and can offer wonderful opportunities, along with the Middle East. That’s why international departments in colleges across the developed world are trying to squeeze themselves into those markets.

Maybe it’s time to try somewhere new, where the odds aren’t stacked against you?

Opinion: Why UK colleges can't compete internationally

News: Colleges struggling to grow international recruitment

Background: Colleges earn £57m from international work

I have long bemoaned colleges that follow the same well-trodden path of their peers, invariably leading nowhere. The popular markets are crowded, difficult and – particularly with India – very price-sensitive. Some years ago, we saw British education pouring millions of pounds of college sector money into India for very little return. The market was there, of course, but it was not going to pay British prices and, unless you understand how your customer will want to buy from you and you can make a profit, it was never going to be sustainable.

There are, of course, many examples of colleges that have had individual success in China, Saudi Arabia and India, but we have to look beyond these saturated markets to new ones that are most desperate for support and ready to work with us.

Technical education: Colleges expanding overseas

Francophone Africa is a great example. I have not come across a single country that does not want to diversify or even replace the current, often bureaucratic, French system with good quality English language education. The market for language learning is almost limitless – there is a real need for English language training in order to compete in the global market. There is also a need for system reform in order to improve opportunities and standards of living. But nobody goes to these countries, because they are perceived as French and, therefore, “difficult”.

Actually, francophone Africa has a very interesting set of circumstances that can make life a lot easier for those looking to establish themselves there. After independence, the French kept an eye and grip on the newly-independent nations, and this has resulted in a great deal of standardisation. The sub-Saharan countries all have the same legal system and the same currency. So if you are successful in one market, you have a strong basis for success across the region.

TVET UK’s sister company, UK Francophone Education, is leading the way on engagement in these markets, looking at ways in which colleges and universities can support the development of education in these nations.

English is in high demand but there is not the capacity nor quality of teaching to meet that demand. Schools want to teach English from primary level, but they don’t have the teachers, particularly in rural areas. We now have more than 20 British teachers living in Mauritania, teaching English and helping to train a new generation of local English teachers.

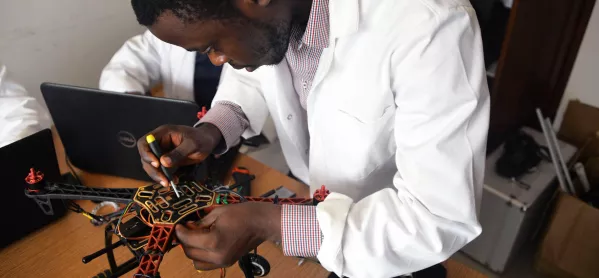

Vocational education development has largely been ignored across the region, yet the jobs required by employers and international investors are in construction, energy, engineering, hospitality, ICT, etc. This is far from unique globally, but it is an untapped resource and the potential upside for focusing here is much higher than traditional markets.

So, if you’re thinking about making one change to your international strategy in 2020, take a look at some of these markets and the opportunities they offer.

Matt Anderson is managing director of TVET UK