- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Early Years

- How has Covid impacted on early years education?

How has Covid impacted on early years education?

When the new cohort of school starters arrived in their first classrooms in September 2020, many in education were watching on nervously.

How had lockdown impacted on their social development? Would their language and communication be at a level suitable to start school? Would they have the stamina and physical development to cope with the demands of a school day?

After all, for many of these children, the first lockdown in March 2020 meant that they lost a lot of time in nursery settings and with other young children or family members, depriving them of vital development opportunities.

One group watching especially closely to see the effects on those starting school were six researchers tasked by the Education Endowment Foundation to answer these questions and more - specifically: “What is the relationship between Reception year children’s experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic and their socio-emotional wellbeing, language and numeracy skills?”

What effect has Covid lockdown had on EYFS?

Now the team, led by Dr Louise Tracey, of the University of York, working alongside five others including Dr Claudine Bowyer-Crane, associate research director for employment and social policy at The National Institute of Economic and Social Research, and Dr Sara Bonetti, director of early years at the Education Policy Institute think tank, have issued their first interim report.

This report is based on survey data from 58 primary schools and their staff, and the views of 673 parents, too - and it makes for intriguing reading.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a key top-level finding was that more than three-quarters (76 per cent) of schools said that pupils starting school in September needed more support than usual cohorts.

“Many children have entered Reception at a much lower level than previous years, particularly in number, mark making and speech, focus and attention and behaviour,” said one teacher interviewed, no doubt echoing the thoughts of many others.

To find out more about this, the researchers then asked about the main areas of concern around pupils’ first engagement with schools - with some clear issues standing out.

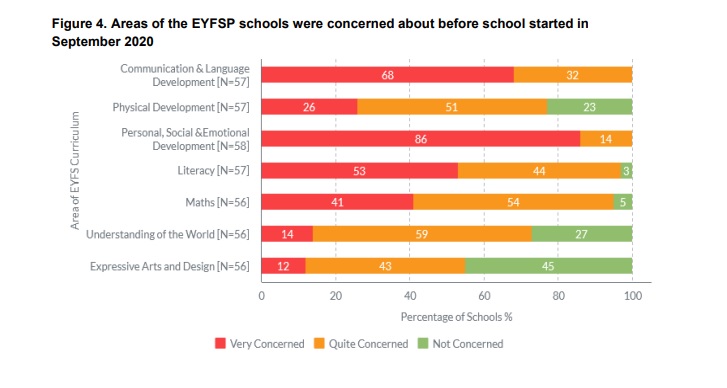

For example, all schools stated they were “quite concerned” (14 per cent) or “very concerned” (86 per cent) about the personal, social and emotional development (PSED) of pupils and about communication and language development (32 per cent were “quite concerned” and 68 per cent “very concerned”). See the survey full responses below.

As such, schools have clearly given these areas a major focus since returning, with 83 per cent of those surveyed saying they were both a higher priority than usual in the autumn term.

Levels of concern easing

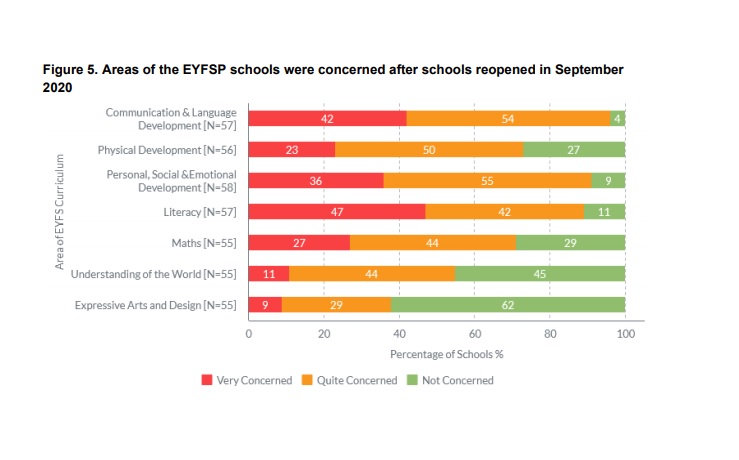

And the good news is that it appears this work has had an impact, with the level of concern over these areas falling notably after schools had been back when the team surveyed the teachers again during October and November of 2020.

For instance, where PSED was cited by 86 per cent of schools as an area where they were “very concerned” before school returned, this proportion had dropped to 36 per cent after reopening.

Communication and language development followed a similar pattern - with the 68 per cent “very concerned” before school reopening dropping to 42 per cent after reopening. See the full responses below.

Dr Tracey says the reductions in these key areas are testament to the work done by teachers since returning to school last year. “Teachers have done an amazing job at mitigating those concerns and they should be recognised for that,” she states.

Parents have clearly noticed, too, with 96 per cent saying they thought their child had settled in well, and 85 per cent of parents did not report any concerns about how their child was coping.

Drilling into the data

Dr Tracey says the next stage of the research is to find out more about the specific work that schools did to help tackle these concerns, and the clear impact it had.

“What we’re hoping to do is carry out some interviews with some schools to get a much richer idea of what’s going on in the schools as well, so that we can really drill down a little bit more and find out more about that,” she says.

More broadly, though, the survey does give some topline insights into how schools tackled the issues, with most schools (52 per cent) focusing on using existing resources, while 23 per cent said they intended to develop new resources aimed at these areas.

Meanwhile, when it came to using outside support, 11 per cent said they would do so and access the National Tutoring Programme, and 12 per cent said they would use the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI) programme.

Language focus

While the 12 per cent figure may be low within the cohort surveyed, wider data published alongside this report by the EEF showed that 6,672 schools had signed up to the programme this school year, covering over 62,000 pupils, with 20,000 teachers and teaching assistants receiving training in this area.

Josh Hillman, director of education at the Nuffield Foundation says this uptake was key as part of the move to tackle communication and language development.

“We encourage all schools who have not yet done so to apply to receive NELI, which will help them to address the communication and language development needs of children starting school later this year,” he says.

“The earlier we can provide this support for children, the greater the opportunity to prevent them from falling behind in developing the foundations of language and literacy.”

The mention here of literacy is notable, too, because in the research report it occupies its own area of focus with 53 per cent of teachers saying they were “very concerned” and 44 per cent “quite concerned” about children’s ability in this area before returning to school.

However, despite 57 per cent saying it has been an area of higher focus since returning, the level of those “very concerned” by this area of school development has hardly dropped, falling just by just 6 percentage points, suggesting that during the autumn term efforts in this area did not have as big an impact as other areas.

The researchers, however, say that in a way this can be seen as a positive as it shows that the importance of literacy remains clearly on the agenda for teachers, but that their initial focus was on the wider communication and language development - something that is key for all subsequent learning.

“Teachers know they can teach children to read with a systematic phonics teaching. But what is less obvious is how to improve overall language and communication, and so that is something they have given more focus to, because they know how much it matters,” says Dr Bowyer-Crane.

Future guidance

The hope will be that in subsequent reports, with another interim study likely in February next year, concerns around literacy will drop, too, as efforts in this area increase and the impact of this is seen by teachers.

However, what that new report will also show is how big an impact the January to March lockdown had on learning, as the data gathered here does not cover that period and only goes up to the end of the autumn term.

“Since this research was conducted, there have been further partial school closures and teachers have been balancing online and face-to-face learning,” the researchers note.

The importance of early years education

Nevertheless, the researchers say the current findings are a vital insight into how teachers adapted to the first term of the academic year, and the lessons learned may well serve them well again after the most recent lockdown.

“I think this shows us where schools were concerned and my feeling is we’ll probably find that these concerns are very similar following that lockdown,” says Dr Bowyer-Crane.

Dr Bonetti adds that insights into how these teachers helped to focus on issues like communication and development and social and emotional wellbeing could prove vital for the 2021 cohort, too.

“Nursery attendance this year is still extremely low, so a lot of children are not attending nursery, so they might be starting a Reception year next year in similar conditions to the children that started in 2020,” she says.

And the insights gained through this report and those scheduled for the future could also help to inform future strategies for school starters and their development, given its importance to their long-term education and life journey, as Dr Bowyer-Crane outlines.

“I think [the report] shows that…socio-emotional skills and good communication and language are the foundation for everything,” she says.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article