- Home

- Four steps to a healthier relationship with tech

Four steps to a healthier relationship with tech

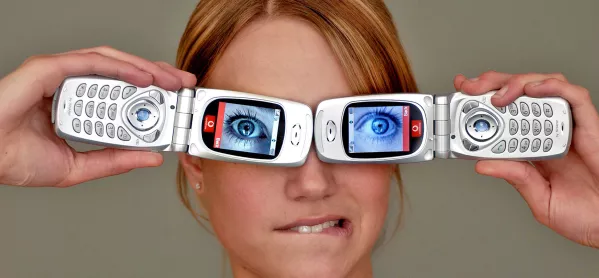

When I purchased my very first smartphone, it was love at first sight; I was awestruck by its elegance and beauty. Not to mention what this thing could do!

My smartphone would be the key — to working smarter, not harder; to getting more done in less time; to finally clutching the Holy Grail of work-life balance. And with my laptop, too? The possibilities were endless. Weren’t they?

Alas. I was so naïve back then, so blinded by the bright lights of my screens, that I missed all of the warning signs: the ping of a late-night email, triggering a flurry of noisy thoughts that left me unable to relax and unwind; the fancy data software that looked great up-front but in reality led to hours and hours of extra input, analysis and report-writing; the extra hours I found myself spending, searching for perfect resources and adding pretty pictures to my Smartboard slides.

Quick read: Five ways I reduced workload and embraced ‘me time’

Quick listen: The truth about screen time, tech and young people

Want to know more? When edtech fails to produce results, it’s tempting to blame the tools. But could the problem really be how we are using them? In the 29 April issue of Tes we share the findings of a new Education Endowment Foundation report into edtech.

I seemed to have only three states of being: working, thinking about working or distracting myself from thinking about working, usually via a screen. I couldn’t "switch off", even when I wanted to.

Smart use of smartphones

And I’m not alone here. According to Ofcom’s 2018 Communications Market Report, the average smartphone user checks or uses their device once every 12 minutes while awake, and the average person spends 24 hours a week online.

For a profession recently shown to be working 9 million extra hours of unpaid overtime per week, we teachers can hardly afford to be losing an entire day to mindless screen-scrolling.

So what’s the answer here? Are we talking "break" or a "break-up"?

Over a decade into my smartphone relationship and still very much in love (though a lot less naïve), I’ve learned that all that’s really required to make this partnership a whole lot more healthy is something that us teachers are already pretty great at: rule-setting.

Here are four rules that will help you maintain a positive relationship with technology:

1. Decide on your availability

Are you prepared to read and answer emails at 9pm on a Friday night? If the answer is no, turn off your sound and pop-up notifications.

2. Take measures to prevent relapse

If you know that you don’t want to look at your phone, don’t rely on willpower alone – move it into another room, keep it on silent or at least turn it over.

3. Measure your data

I downloaded an app called Quality Time, which breaks down my daily internet usage. While I still haven’t gotten over the initial shock of it (what on Earth was I doing that one day I spent 48 minutes on Pinterest alone?), seeing how much time I was spending online has scared me into becoming a more mindful phone-user.

4. Imagine your phone is a person

Would you allow another person to wake you up with horrifying news bulletins from thousands of miles away; to tug at your shoulder shouting “Miss!” or “Sir!” when you’re clearly engaged in real-life conversation at that moment; or to interrupt your romantic meal out to discuss next term's learning walks? No. So don’t allow your phone to, either. You control where your attention goes, not your technology.

Jo Steer is a teacher and experienced leader of special educational needs and disability interventions, as well as wellbeing strategies

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles