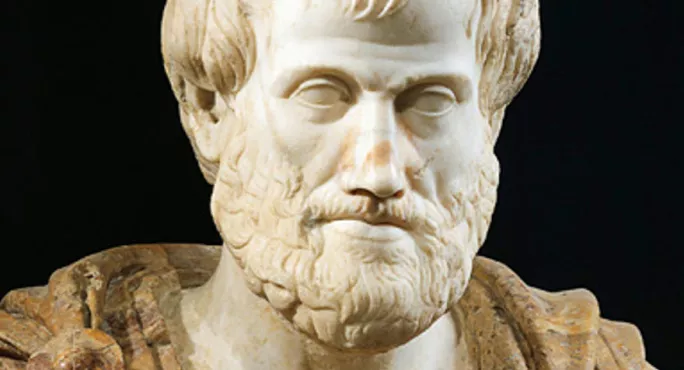

‘How a focus on Aristotelian ethics can develop good digital citizens’

It may sound far-fetched, but I believe the ancient Greek philosophy of Aristotle can help in tackling some of the moral issues encountered by young people on the internet today.

Indeed, a reconsideration of virtue ethics and a focus on character could help to counter some of the problems that teachers face daily, such as cyberbullying and online plagiarism.

In dealing with such issues, most schools adopt strategies along deontological or utilitarian lines of thinking. Deontological philosophy is based on the principle that it is one’s duty to follow rules and guidelines to “do the right thing”. Displaying rules in corridors and classrooms about how to avoid plagiarism is an example of this philosophical principle in action.

Utilitarianism, meanwhile, is based on the principle that the “right thing to do” is the action that brings the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. This involves calculating what the consequences of any particular action might be. Strategies that follow this principle often involve showing students shocking films about, for example, Amanda Todd, who killed herself after being cyberbullied, in an attempt to elicit empathy and make them aware of potential unintended outcomes.

Although teachers report that both strategies have some effect, issues of online behaviour are still very real concerns in many schools. This is why I believe that educational strategies directed at developing good digital citizens, based on Aristotelian virtue ethics, are worth considering.

The strength of virtue ethics is that it emphasises good character as the best guide for “doing the right thing”, alongside adhering to rules and attempting to calculate the consequences of a course of action. In the cyber worlds that many young people inhabit, rules are particularly hard to establish and uphold, and consequences are difficult to predict.

Rules were made to be broken

Recent research conducted by the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues at the University of Birmingham, where I work, shows that 11- to 14-year-olds in England think the internet is largely unregulated and that rules about what is right and wrong are often opaque. Although participants say that their teachers enforce rules in the classroom, these are often broken when they are at home alone, online in their bedrooms.

Website giants such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter find it hard (or are sometimes unwilling) to regulate personal profiles or impose rules regarding their use. Furthermore, even when the rules are understood, young people report bypassing them by going online anonymously.

The research also shows that many 11- to 14-year-olds are unaware of the consequences of some of their online actions. For example, they post messages that they don’t realise will upset their peers because of a lack of visual clues compared with a face-to-face interaction.

Furthermore, because the journey of any online communication is so unpredictable, messages that were intended for one individual can quickly spread around a whole school, with significant unintended consequences. Many teachers report having to deal with fallouts from supposedly private emails, or “sexting” posts that have been widely broadcast.

A particular challenge for schools is that offline strategies can’t simply be adapted for online use. A clue as to why this might be the case can be found in how young people describe the internet. In focus groups, they make a distinction between what they believe to be the “real” offline world and the “unreal” online world. Many describe how in the online world they believe that anything goes and all bets are off, possibly explaining why they act and behave differently.

The research shows that young people have a greater tendency to experiment online, perhaps by pretending to be a different person. Likewise, they report that they are more likely to commit unvirtuous acts online than they would offline: they might bully online but not face to face; they might plagiarise from a website but not from a book; they might download an album illegally online but not steal a CD from a shop.

The fact that rules are hard to uphold in the virtual world, and consequences difficult to predict, makes an approach to dealing with online moral issues based on character virtues appealing. Such strategies should aim to develop digitally wise citizens who are able to self-police their online activities. This requires schools, as well as parents, to cultivate attitudes and dispositions in young people that help them to understand what the virtuous action is in any given online interaction.

Of course, virtues can’t simply be taught in the classroom; they must be learned through practice, experience and the development of what Aristotle called phronesis, or practical wisdom. The challenge, therefore, is to create educational strategies inspired by virtue ethics that can be successfully delivered in schools.

A question of character

The recent (re-)emergence of character education offers a great platform for the development of online practical wisdom. Character education, delivered well, encourages young people to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses and assess their actions and behaviour, with a view to moderating them if required. Character education is mostly “caught” through a school’s culture and ethos. However, it can and perhaps should be “taught” through and within all subjects - for example, a reimagined computer science curriculum aimed not simply at imparting computer literacy but also at the development of good digital citizens.

This would require teachers to provide time and tools for their students to reflect on and learn from their online interactions. The teaching tools to support such an approach could be hosted on websites, such as structured reflection blogs or moral dilemma games, where students could practise making difficult ethical decisions. Such tools would help young people to develop the capacity to acquire online practical wisdom and take the compassionate, honest or courageous action, even when no one was watching.

It seems that the ancient Greek philosophy of Aristotle offers some hope for teachers dealing with some very modern problems. Applying virtue ethics principles to the modern world might just make virtual reality a more virtuous reality.

Dr Tom Harrison is director of development at Birmingham University’s Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues

To read more, get the 12 June edition of TES on your tablet or phone, or by downloading the TES Reader app for Android or iOS. Or pick it up at all good newsagents.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters