- Home

- How to make group work a success

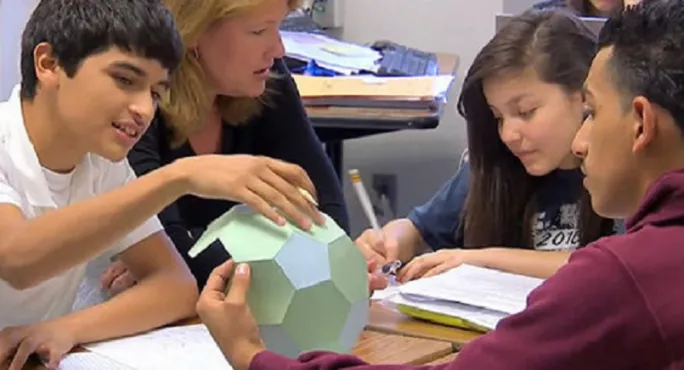

How to make group work a success

“If you can’t do things well and if you haven’t been well trained in the properties of successful group work, then you may set up a task that misfires badly,” states Christine Howe, emeritus professor of education at the University of Cambridge. “And if you have a negative experience, it’s human tendency to assume that’s the truth. I suspect there is a little bit of that because when I see [negative] quotes [about group work], they are usually generalisations from personal experience.”

Such a statement will be contentious in certain teaching circles. Many teachers believe group work is a complete waste of time and energy because it can cause behavioural problems and actually limit students’ understanding. As such, they argue that teachers should stop doing it.

But Howe insists the evidence is clear that, when done well, it works, particularly if you want children to master the curriculum. She says several studies show that children, through successful group work with their peers, can develop a better understanding of concepts in just about any subject (but it’s more commonly used in science, technology, engineering and maths lessons, and that’s where most of the research into the effectiveness of group work has taken place).

Another spin-off benefit of group work, she notes, is preparation for employment after children have completed their studies. “In the world of work, teamwork - as we all know - is important and working together in groups at school helps prepare children for those different social rules,” says Howe.

There are arguments to counter these claims, but a synthesis of the evidence from the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that, overall, collaborative learning has a positive impact.

But this all depends, as Howe says, on group work being done well. So what needs to be put in place first?

1. Agree the rules for group work

Howe says that working with students to draw up a set of rules is essential, as it creates buy-in about how group activities should work. She says rules could include the likes of “we make sure that everyone says what they think”; “we listen respectfully to everyone’s ideas”; and “when we disagree, we give reasons for our opinions and try to resolve our differences”. These rules should be prominently displayed in the classroom and regularly referred to.

2. Choose the right topic

“Not every task is going to profit from group work,” says Howe. “You want a task where there will be a range of different opinions among the students.” She says a poor choice of topic or task is one of the main reasons why group work fails. “If the solution is too obvious or too hard, the students won’t have productive discussions. The topic must be challenging and amenable to a range of opinions, but not impossible,” she adds.

3. Keep in mind social dynamics

You have to know your students well, says Howe. If you do, then you can create groupings that take social dynamics into consideration, ensuring the right mix of students to enable good discussions.

4. Don’t be a helicopter teacher during group work

“The reason I don’t think that’s very helpful is there is quite a lot of evidence that, to enjoy the optimum effects [of group work], children not only have to engage in the group interaction, but they also have to think a little bit afterwards,” says Howe. “You won’t necessarily get the optimum outcome within the group itself immediately after the conclusion of their interaction. The children need to go away and put it all together.

“In some of my research, I’ve found that progress has been made over quite a long period after the groups [ended], so if teachers jump in too quickly or too explicitly, they can sometimes undermine that process of ‘post-group reflection’, as I sometimes call it.”

You can read an interview with professor Howe in the 21 September issue of Tes

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters