- Home

- ‘It’s time to bring back the polytechnics’

‘It’s time to bring back the polytechnics’

Improving England’s technical education is certainly high up on the political agenda.

For all the furore and disagreements about the way the government is handling the introduction of T levels, the controversy surrounding them has helped spark a lively and innovative debate in the FE world about what it will take to make them a success.

One thing, however, is becoming clear. Unless we build a distinctive and more effective post-18 technical education delivery eco-system then over the coming years, the ambition of a new “gold standard” in qualifications and better opportunities for young people is unlikely to fully materialise.

The planned T level industry placements demand a step-change in the capability of our schools and further education providers to effectively engage with employers. General further education colleges have a chequered history in this regard, as do many of our universities.

‘Danger we end up with a postcode lottery’

Moreover, there is the unresolved issue of what T levels are a progression on to. Ministers say they will address the productivity and skills gaps the country faces by taking the work of employer-led panels and transposing their requirements into a “world-class” practical study programme leading to gainful employment.

But the Department for Education has so far published no real econometric studies that map the demand for these occupational skills by locality in England and the planned availability of the new T levels.

The danger is that we end up with either a postcode lottery of post-18 technical education provision in the future, or we repeat the same mistake of programme-led apprenticeships - simulation work-based courses that young people were dumped on with no real prospects of getting a job.

T levels will be offered at level 3 only, so it raises the question of what other qualifications will successful completers progress onto.

Are the universities going to give them equal value in terms of UCAS points for undergraduate degrees as they do for A levels? And what will happen to the current applied general qualifications, like BTECs, which have proved very popular with learners and employers?

Indeed, which institutions are best placed even to offer level 4 and 5 qualifications is itself a pressing challenge, when the trend in recent years for universities has been to abandon two-year sub-degree courses such as the higher national diploma (HND) and higher national certificate (HNC)?

‘A serious question’

The Association of Colleges has suggested a new suite of higher education (HE) qualifications taken forward by its members. College leaders bemoan the fact the sector struggles for national recognition - not only in perpetual poor funding settlements - but the absence of a nationally recognised brand.

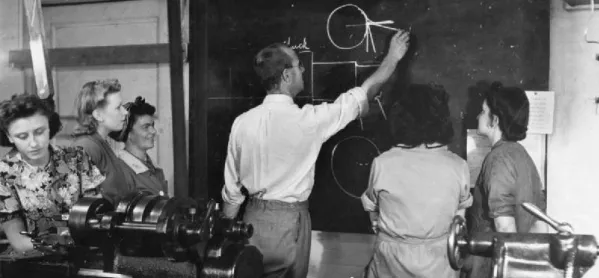

Of course, the historical irony of this position is not lost on those who have been around the sector for some time. In the 1950s and 60s, we had the emergence of a strong national brand of higher technical education, and it was called the polytechnics - or the “polys” as they were more commonly known.

At the same time, more than 400 further education colleges, many with “technology” in their titles, saw a 1,200 per cent increase in public funding. By the summer of 1968 there were well over half a million FE students on “day-release” from their employers, reflecting perhaps the more optimistic side of Britain’s post-war industrial strategy.

Fast forward to the present day - with the advent of the fourth industrial revolution - a serious question has to be asked: should we bring back the polytechnics?

The critical difference this time is that the use of the “poly brand” should be restricted to those further education colleges that excel in technical education from level 3 - the new T level routes and applied generals - up to full degree and post-graduate level equivalence.

A national network of around 80 college polytechnics, absorbing the existing University Technical Colleges (UTCs), could be created, with full access to Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) funding and the student finance system.

Something has to change. In hindsight, the 1992 Higher Education Act that ended “binary-divide” between universities and polytechnics was a massive mistake. It was borne out of academic snobbery and a political class that believed by making all degree-level education the preserve of non-binary university status, that this would drive the knowledge-driven economy.

In truth, creating a singular type of higher education institution - by rebranding the old polys - cynically helped switch on the money printing presses at the Treasury, as social demand (increased graduate numbers pushed by policymakers) trumped economic demand in terms of the higher technical level skills the country actually needed.

Underemployment and underutilisation of skills

This coincided with the collapse in the youth labour market throughout the 1980s and 90s, as successive governments have effectively used HE as the means to take up the slack.

It’s only now that the failings of this policy are becoming fully apparent. Studies of income tax records, including research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, show the so-called “graduate wage premium” argument for traditional degrees is waning.

Many of the roles young people find themselves in following three and four-year university courses do not require a traditional degree.

Underemployment is now rife. According to a survey carried out by Accenture Strategy, seven in 10 recent graduates feel the job role they are doing is an underutilisation of their abilities. Meanwhile, a decade of poor productivity performance and the growing skills gap is becoming deeply troubling as the country prepares for Brexit.

Bringing back the polytechnics would act as a significant counterbalance to this negative trend. It would give the FE college sector a strong national brand to rally behind. The old polys were quality assured and nationally co-ordinated by the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA).

It meant that degree courses were standardised and high quality regardless of where they were being offered. Working closely with awarding bodies it would make sense to bring back a version of the CNAA - perhaps overseen by the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education working with Ofqual - to ensure the labour market relevance of technical degrees, linking them with degree apprenticeships.

Over time, we would probably see the reduction in traditional bachelor degree programmes as young people opt to pursue two-year technical degree courses, leaving them with less graduate debt and better employment prospects.

Two-year technical degrees?

For too long FE has been starved of funds as universities have accessed public resources to expand full-time undergraduate courses. Expenditure will top £20 billion per annum by the mid-2020s according to estimates from the Office for National Statistics.

Forecasters predict that 45 per cent of the student loan book may actually never be paid back, placing the burden of repayments squarely on the taxpayers not yet born.

This is the central conundrum that former banker Philip Augar will have to tackle as part of the post-18 education and funding review - launched by the prime minister at Derby College in February.

The reinvention of polytechnics, and two-year technical degrees, delivered by reinvigorated FE colleges, might be a very good place to start.

Tom Bewick is chief executive of the Federation of Awarding Bodies

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters