- Home

- Judith Kerr: ‘Grammar is like drawing - if you want to do it, you want to get it right’

Judith Kerr: ‘Grammar is like drawing - if you want to do it, you want to get it right’

This profile was orginally published on October 27, 2017 in Tes magazine.

Judith Kerr is apparently never late. This morning, however, the 94-year-old children’s author turns up late to the Langham hotel in central London, her hand wrapped in bandages. She caught it in the Tube barrier, she says, and scraped off a large section of skin.

“That happens when you’re this old,” she says, cheerfully. “The skin’s very thin.”

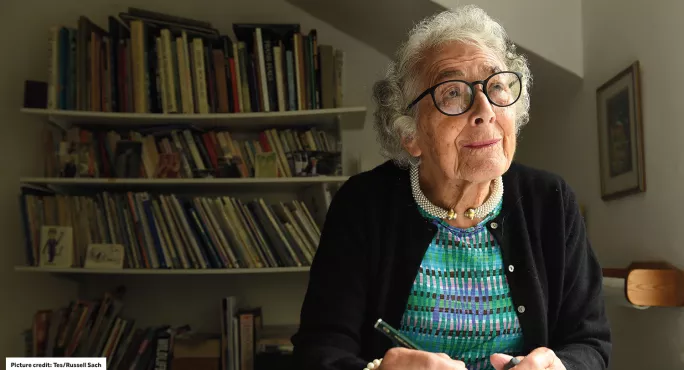

She is tiny and grey-haired. If one were to describe what a grandmother ought to look like, it would be very much like Judith Kerr. Her hair is set; she is dressed in a neat skirt and maroon blouse.

“It matches my blouse,” she says, holding up her blood-streaked hand, then sits down and orders a Martini Rosso.

Inasmuch as anyone qualifies as a national treasure, Judith Kerr does. She is the author of the picture book The Tiger Who Came to Tea, as well as more than 30 other children’s titles.

And unlike many other high-profile children’s authors, such as Philip Ardagh, Joanna Nadin and Matt Haig, Kerr does not condemn grammar teaching as off-putting and irrelevant to good writing. Instead, she believes that children benefit from learning formal grammar.

“I always wanted to write correctly, you know. Just as, if you’re drawing - if you want to do it, you want to be able to get it right,” says Kerr. “I always found it quite interesting to learn about grammar.”

On the run in Europe

Among Kerr’s most famous books is When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, her autobiographical account of fleeing 1930s Germany as a child. Her father, Alfred Kerr, had been a journalist in pre-Reich Germany. In the years before Adolf Hitler seized power, Kerr senior made fun of the soon-to-be dictator repeatedly.

The family fled first to Switzerland, but the Swiss newspapers refused to employ Alfred Kerr, for fear of offending Hitler. So the Kerrs moved to Paris and, later, to London.

“Both my brother and I have always agreed that the childhood we had as a result of Hitler was infinitely better than it would have been if there’d been no Hitler,” Kerr says. “We found it so interesting - all these different schools.”

Her transient childhood also taught her the value of learning foreign languages. “Learning a language that’s incomprehensible, and then within a year or so you can speak it…I mean, the difference between German and French is enormous. German tended to be these long, long sentences. And French - I thought it was fascinating, wonderful, that you could say things in a few words. And English was totally different again.”

There is, she says, a significant benefit to learning a foreign language at an early age: “I think it seems to be a very good thing for children to learn something quite difficult very early on. And perhaps growing up with two languages, as refugee children do, it’s not only good for their view of the world, but it seems also to be good for the brain.”

In France, she says, she enjoyed “parsing”, where “you wrote a sentence and there was a gap above, and you wrote above the words ‘verb’, ‘noun’, ‘adverb’. That was quite interesting.”

Kerr was an artist before becoming a writer: as a child, she was always drawing. In fact, among the items that Kerr’s mother packed as the family fled Germany were nine-year-old Judith’s drawings. These are now held at Seven Stories, the national centre for children’s books. But she says her willingness to learn from her teachers did not extend to art lessons.

“I tended to fall out with my drawing teachers at school, actually, because they always wanted me to draw whatever they thought I should draw - that they would have liked to draw themselves,” recalls Kerr. “I think mostly children just like to be left alone. I had a very nice teacher in Germany who just let me do what I wanted, and that was fine. But then I had others who - they had a picture in their mind of what they wanted the children to do. And it was personal, it was private.”

In fact, she is adamant that creativity is not something that can be taught. “You can’t teach people to be creative - they have to want to be creative. But if you see somebody do something - a child - that it just does because it thought it would, I’m sure it’s good to say, ‘This is very good. Why don’t you do another one?’”

Reading between the lines

As a child, she enjoyed drawing scenes of disaster: shipwrecks, for example, and fires. Surely, then, it is not too large a leap to see The Tiger Who Came to Tea as a disaster story (a tiger turns up for tea, and eats and drinks everything in its hosts’ house). But Kerr bridles at the idea.

“Tiger to Tea wasn’t a ‘disaster’,” she says. “It was a triumph - a wonderful day, as far as we were concerned. It all depends on how you think of tigers. If you think a tiger - ‘Ooh, it eats people. It’s dreadful. It has claws. It bites’ - well, then you wouldn’t want it to come to tea.

“If you look at it - I just think, look at that orange and those black stripes, isn’t it beautiful? And look at that fur - I want to stroke the fur. Well, then you would have to take a different view. But obviously it would be hungry because it was very large. If it came to tea, it would eat rather more than other visitors.”

The children’s author Michael Rosen has a theory that the tiger represents the Gestapo: the ultimate unwanted guest, muscling its way into the house. Kerr demurs. She is too polite - and injured - to wave her hand in dismissal, but that is the essence of her reaction.

“I love Michael Rosen, and he knows I think this is mad. For one thing, I was so lucky: I never saw the Gestapo. I never saw anything bad happening in Germany. Never. Because we left before Hitler took over.

“I think if we’d stayed even a week longer, it would have been very different. So, no. I wasn’t haunted by anything.”

Despite her popularity, Kerr insists that she is not an icon. “It feels like a mistake and something that sooner or later somebody will realise,” says Kerr, in the neat received pronunciation typical of her generation. “It’s largely because I’m so old, I think. I talk about the war. And there are very few people now who are in that [age] range, and certainly not many who remember Hitler.”

Kerr’s latest picture book, Katinka’s Tail, about a cat with a distinctive tail, was published this month. She is already working on a new book.

“I would be miserable if I weren’t working,” she says. “It means you get up in the morning, you have a plan. It’s something that pulls you along. I have so many widowed friends, and they all find something [to occupy themselves], usually. One I know does an awful lot of charity work, which is marvellous and helps people. But work is really the only answer [for me]. I can’t imagine not being able to draw.”

She pauses and glances down at her bandage. “I’d better get this hand seen to.”

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters